Cameras and kilns: Inside the whimsical world of this creative couple in Tīmaru

For the love of a good image… Simon and Nachiko Schollum have fun in their front yard photographing one of Nachiko’s sculptures.

Several generations of two families — one Japanese, the other Bohemian — live on in the work of two artists, a couple working in Tīmaru.

Words: Nathalie Brown Photos: Brian High

Artist Nachiko Schollum draws on the influence of her mother, Sachiko Takahashi (now 86 years old), who is proficient in many of the classic Japanese arts. Nachiko’s artist grandfather Ryuei Matsumura also painted landscapes in Europe throughout the 1930s.

The granddaughter and daughter of artists, Nachiko finds passion and self-expression in what she calls her “inner conversations”, which come to life in an array of fired clay forms. When working on her art, she might browse illustrated books and magazines, searching for inspiration. At other times, she will spend the entire day working in clay.

“My current focus is raku pottery, sculptured character studies and glaze art,” she says. “I also combine different materials and glazes fired at varying temperatures to produce abstract pieces.”

Nachiko follows in her mother’s footsteps, with talents in ceramics and felting, piano, mandolin, and ukulele.

Nachiko came to ceramics relatively late in life. “I attained a law degree in Tokyo,” she explains. “If I had stayed in Japan, I would probably have specialized in criminal law.” When she graduated from university, her parents gave her a choice of gifts: a kimono or international travel — same cost.

“I traveled around Europe and the Middle East, making my way Down Under in 1988,” she says. “I was studying English and having a working holiday. I held positions at Mount Cook Tours in Christchurch and the Japan Travel Bureau in Auckland. I also worked in Wellington.”

In Auckland, Nachiko learnt ceramic painting and how to make pots using her hands as well as a wheel at the Mairangi Bay Arts Centre. She met police officer Simon Schollum through a mutual friend in 1991 and was interested in the fact that he was using his photography talents professionally.

- Membership of the South Canterbury Pottery Group gives Nachiko access to other potters and ceramicists, all committed to helping each other develop and refine their techniques and style. Here she is glazing, the careful detailing requiring the aid of a magnifying glass.

- A work from a series titled March Hares and Funky Rabbits.

- Pieces inside the kiln ready for their first firing.

- In a different style again, a series of bisque heads await glazing

Even though he is 1.93 metres tall and a compulsive conversationalist and she is no more than 1.52 metres and shy, they saw themselves well matched. “We married in 1993 and moved to Tīmaru 10 years later with our then five-year-old daughter, Linden.”

Linden is now 24 and a radiographer. Her parents see her career as carrying on the family photography tradition. Nachiko has developed about 100 pottery glazes and is constantly experimenting, keeping a detailed record of everything she does. Of her glazes, she says: “Sometimes, experimentation leads to something extraordinary but often disappointment too.”

She has been a long-time committee member of the South Canterbury Pottery Group, has won awards, and exhibited in South Canterbury, Hawke’s Bay, Whanganui, and Waikato. Her hand-built pottery ceramic busts of imaginary and historical characters are for sale at the McAtamney Gallery & Design Store in Geraldine, the York St Gallery in Tīmaru and Gallery De Novo in Dunedin.

- Mind’s Eye is part of a series of character studies, as is Level Two Warning (next picture).

- Winter Rabbit, made by Nachiko for the young child of a friend.

Simon’s forebears came to New Zealand in 1863 from a village just south of Prague in what was then Bohemia, now the Czech Republic. His father, Stanley, was also proficient with cameras, becoming one of the first police forensic photographers in the late 1930s.

His maternal grandfather, H.C. Gore, an acknowledged pioneer filmmaker and photographer, operated the ACME Studios in Dunedin from 1896 till the 1960s.

Simon’s police career spanned 40 years, and he mainly worked as a forensic photographer in Australasia, the United States and Singapore. “I fell in love with photography after receiving my first camera at 11. My father encouraged me to learn a trade, so I joined the New Zealand Army Combat Engineers at 18 but soon transferred to the military police.”

- Simon and his Hasselblad.

- It usually takes several days for Simon to finalize a photograph. Here, he has set up a still-life with red peppers. He generally uses Broncolor lighting with lenses from Zeiss, Rodenstock, Linhof, and Hasselblad.

His aptitude with a camera and an eye for detail led to him becoming the first official military police photographer. After six years, he joined the New Zealand Police, then transferred to the Auckland police photographic section, helping pioneer fluorescent imaging of fingerprints using the argon-iron laser at Auckland University.

National and international photography awards followed, and he was a senior advisor at the national police HQ and police college, developing the NZQA curriculum for police photographers.

In 2003, having spent two years as a senior advisor on photography projects, Simon wanted to return to front-line forensic photography duties. He and Nachiko considered the several South Island locations on offer and chose Tīmaru.

Peonies, from the Small Room series.

“We were attracted by its locale, and we still are,” he says. “We can sit in a café overlooking Caroline Bay, which is a lovely place. We have easy access to the coast, the rivers and the mountains. The services and infrastructure are as good as you’ll get elsewhere.

“There’s plenty to do here. Nachiko belongs to several arts-focused groups and associations, and I was able to bring my mother here to a very well-appointed retirement village. And perhaps best of all, for me, is the fact it’s not Auckland.”

Since retiring from the police in 2016, Simon has concentrated full-time on commercial, portrait and fine-art photography. For the past eight years, he has featured in the International Garden Photographer of the Year, the world’s premier competition and exhibition specializing in flower, plant and garden photography and the resulting grand annual publication.

Making it into the exhibition series is more than impressive — the competition attracts some 20,000 entries worldwide. Simon’s works have been category winners since 2013, and his 2017 supreme award-winning still-life Pomegranate print placed him at the top of the fine-art photography ladder internationally.

The main exhibition is held annually at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, London, with a succession of touring shows in Britain, throughout Europe and North America. Like so much else, these have been postponed because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

However, Simon continues to work and says he is seeking his own approach to still-life subjects by concentrating on the qualities of elegance, simplicity and precision. “As a photographer, you need to control your process. You need to guarantee clarity, fidelity, and sharpness to inform the viewer. You need to light it to be informing. That is different from lighting for effect.

The award-winning Pomegranate.

“To master still-life photography, I follow the work of the great painters.” For lessons on applying light, Simon looks to Willem van Aelst [1627 to 1683]. For strength in simplicity, he observes Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin [1699 to 1779].

For sensitivity of vision, Clara Peeters [1594 to after 1657] and for a forensic understanding of shadows, he turns to Leonardo da Vinci [1452 to 1519].

“Shadows give depth. The light-dark effect suggests a third dimension. Once I had brought these elements together, people began to ask me whether my photographs were paintings.”

- Fittingly, the artistic Schollums live in an Arts and Crafts home.

- Simon’s study is on the right, off the home’s handsome front hallway.

Simon is pleased when people comment on how painterly his prints appear. “This visual effect comes from applying, in differing proportions, the four canonical painting modes of the Renaissance. For hundreds of years, artists have juxtaposed light and dark values to establish visual structure united by a wash of colour. This results in paintings that look like photographs and photographs that look like paintings.”

It is not just the old masters whose work has influenced Simon’s. He has regular conversations and correspondence with contemporaries Christopher Broadbent in Milan and Francois Gillet in Morocco, both celebrated commercial photographers who, for decades, have been at the top of their field.

WHAT’S SO INTERESTING ABOUT A BOWL OF FRUIT?

Simon Schollum was inspired to take up still-life photography when he saw British floral photographer Mandy Disher’s work in a volume of the International Garden Photographer of the Year.

He recognized the opportunity to use his forensic photography techniques to create still-life images that could absorb the attention of people who would probably otherwise be distracted by digital media.

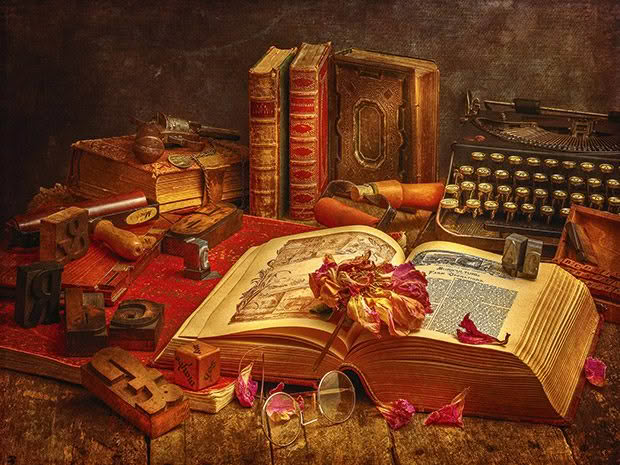

An image from the series, My Grandfather’s Favourite Things.

“I see still-life as an opportunity to tell the story of an inanimate object rather than reveal the character of a person,” he says. “The still-life gives the viewer a new way to interpret ordinary objects. “The arrangement, lighting, backdrop, filters, and so on lend a new meaning to the object.

“From my perspective as a photographer, I can spend infinitely more time arranging and lighting a piece of fruit — as in my [IGPOTY supreme award-winning] Pomegranate — than I would be able to spend organizing a person for a portrait.”

Simon titled his photographic still-life, Botanicals.

Simon’s Grandfather’s Favourite Things series — which features leather-bound volumes and wire-framed spectacles — tells the viewer much about his grandfather H.C. Gore, who led the ACME photographic studio in Dunedin.

Similarly, Simon’s Books series — where guns and knives are counterpoised among old books — are set in a room aglow with what looks like candlelight, conveying a nod to Sherlock Holmes. The weapons, in turn, hint at the character of the photographer, an expert in forensics.

MORE HERE

Ōpōtiki artist Fiona Kerr Gedson transforms feathers into Nepal-inspired mandalas

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.