Poultry anatomy 101: What happens when a chicken eats

A guide to everything that happens in the digestive system after a hen gobbles up its meal.

Words: Sue Clarke

A chicken’s appetite is driven by its requirement for energy (calories) and protein. If its diet is high in fibre and low in fat and protein, it will eat more to try and reach its daily target for these nutrients.

When a hen gobbles up every scrap of your home-made porridge, left-over rice, surplus spaghetti or milk-soaked bread, it is not thinking about taste or texture. It’s packing away as much of this food as possible because it is low quality (in terms of fat and protein) and it knows it will need much more to fulfil its daily nutritional needs.

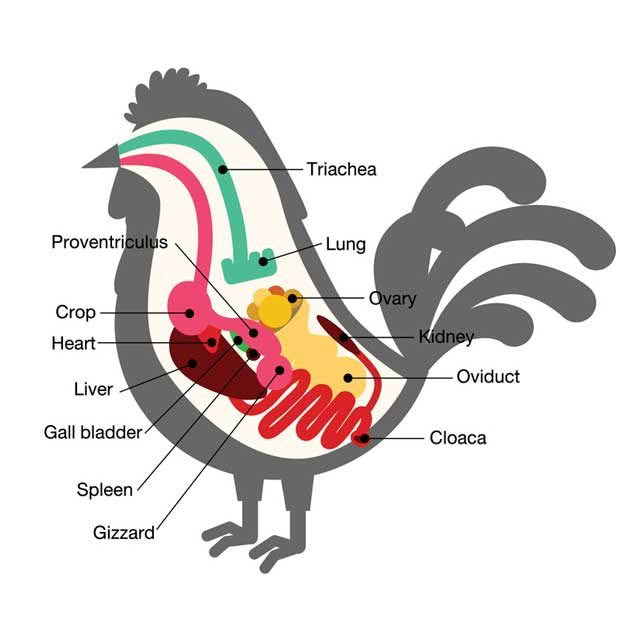

The poultry digestive system is very different to mammals. Before you get to the workhorse intestines, there are three chambers which each carry out a different function to enable the intestines to extract the best value from what it eats.

The first chamber is the crop. This is a sac at the front of the bird’s chest which can expand to about the size of an orange in a big bird when filled with feed. It is merely a storage organ where some digestive enzymes in the saliva start breaking the food down. It allows the bird to rapidly eat a quantity of feed at one time so it doesn’t have to stay in an at-risk area for too long.

In a healthy bird, the crop will be full in the evening when it goes to roost, slowly reducing in size overnight as food is processed. By morning it will not be noticeable.

The next chamber is the ‘true stomach’, the proventriculus. This is where most of the enzymes are added and churned amongst the material coming in from the crop.

A chicken’s gizzard is a complex muscle. Small stones (grit) sit in folds inside it, helping to grind food as it passes through.

Food then moves into the gizzard, a muscular organ that squeezes and grinds the food particles to a fine mush. The gizzard contains small stones (insoluble grit) which the bird swallows to aid the grinding process.

Once thoroughly ground up, the material passes along into the intestines where the various nutrients in simple form pass through the intestinal walls and into the blood stream to be further processed or stored.

The remaining fibre and husks are excreted as pooh, along with the ‘urine’, the watery white urates that are released at the same time.

READ MORE

3 common respiratory diseases affecting New Zealand chickens

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.