Biochemist Iona Weir discovers secrets in New Zealand soil

A spirited New Zealand biochemist and entrepreneur is finding ways to support women in science on her own home soil.

Words: Emma Rawson Photos: Vanessa Lewis

It goes against the laws of science and reason, but there was something a little spooky about the way Dr Iona Weir found her property in Waiatarua in the Waitakere Ranges. It was as if a cosmic force drew Iona, a biochemist and microbial scientist, and husband Chris O’Brien to the cliff-edge property in the thick of the native forest. It had many strikes against it.

The building – a dinky, practical house with no character – was perched on a scratch of flat land at the top of a drive so steep it would leave mountaineers breathless. Then there was a hulking rewarewa smack-bang in the middle of the city views, like a basketball player at a concert.

While many would curse the view-blocking rewarewa, biochemist Dr Iona Weir has nurtured it and harnesses pollen for use in her prebiotic eczema medicine.

“The house probably wasn’t sensible, but there was just something about it. I could see so much potential. It’s the only place in my whole life that’s felt like a home,” says Iona.

Iona had an unconventional upbringing. Her father, a truck driver for the Ministry of Works moved constantly around the country meaning Iona attended 31 schools. It isn’t perhaps the imagined childhood of a top scholar whose PhD was judged best in the world in 1997.

When Iona and Chris purchased the land 20 years ago all that existed on it was a small, unfinished house with a tiny window facing the city. They renovated and extended, designing a home that maximized the city and Manukau Harbour views, with a home office for Iona.

But a logical hypothesis would be that the repeated relocations helped her adapt to any environment. That would include finding a home in Waiatarua with its reputation for being dreamcatcher hippie-ville. (In fact, there are seven other scientists in the small artistic township. Conclusion: avoid observer bias.)

Iona and her husband had lived in Toronto, (where she researched the programmed cell death of plants) and in Chicago, Illinois, and Virginia for Chris’ human resources job. The applications of her work include cancer treatment, skin care, digestive health and the development of crops which are resistant to drought and pest. Pharmaceutical companies have offered her jobs all over the world, but there was something bewitching that patch of bush in west Auckland.

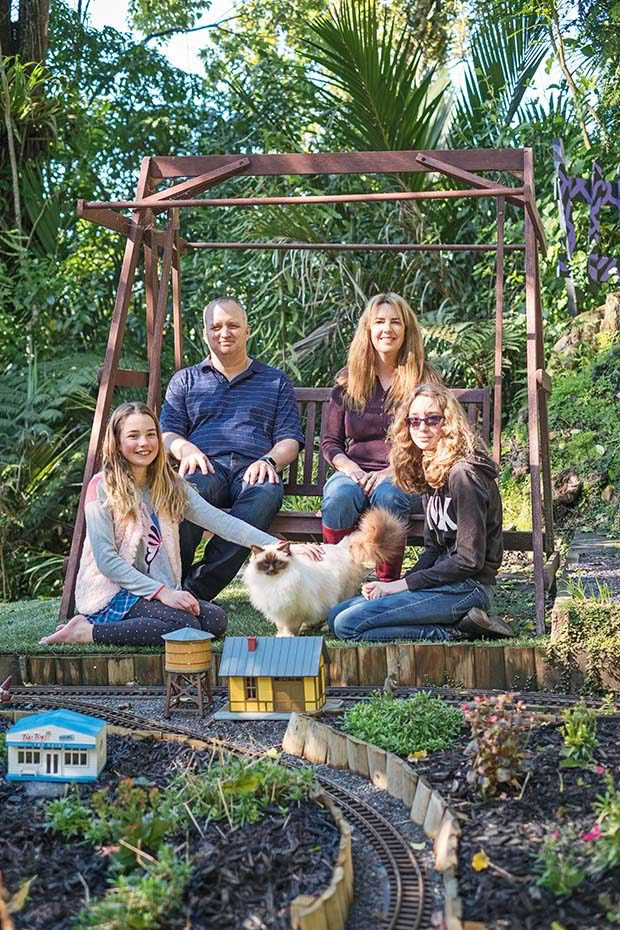

Chris and Iona with Tesscinta (left), Siannah and Nelson the birman are model citizens sitting next to Chris’ garden railway.

If there is magic in New Zealand, it comes from the unique microflora of the land, she says. The soil bacteria and fungi found in Aotearoa’s ancient earth, isolated from the rest of the world since its land mass broke away from Gondwana, is what gives native plants such as manuka, kawakawa and rewarewa their famed medicinal and antibiotic qualities.

“It’s not manuka as we know it without the bacteria. The soil bacteria and fungi give those trees their immune system – it’s symbiotic.”

An ornamental mushroom adds to the magical vibe in the family’s garden.

The garden Iona has created at home in Waiatarua is a world apart from the manicured greens of Oamaru Public Gardens where, as a student, she worked as a gardener. Her garden is Harry Potter-esque, with purple garden stones and statues of chess pieces and fairies.

Chris is a member of the Auckland Garden Railway Guild, and collects vintage railway pieces and trains and models. Tesscinta joins him in building the train village that circumnavigates the trampoline and, together, they attend all guild meetings.

Chris also has a garden railway, which runs around the trampoline. It’s designed as outdoor fun for their daughters, Siannah (13) and Tesscinta (11) but with a practical side.

“I had my kids play in the dirt when they were young. I didn’t want them to actually eat the dirt, I just wanted to expose them to the bacteria and fungi in the soil to build up their immune systems.”

Big Pharma is sniffing around New Zealand’s native plants, and Iona is worried about keeping the intellectual property and research about New Zealand’s soil bacteria on home soil.

“I have seen some international companies claiming their products have New Zealand compounds in them. I love New Zealand, and launching my own company was my way of keeping the research and the business here.”

Iona’s business Decima Health launched Atopis, a patented eczema, psoriasis, acne and menopausal skin treatment range earlier this year. Atopis follows a handful of products Iona has initiated in New Zealand while working at other firms, including the prebiotic Phloe, and New Zealand’s top-selling gastrointestinal health product, Kiwi Crush, a kiwifruit digestive health drink used in hospitals to help patients after surgery and cancer treatments.

When working as director of microbial screening company BioDiscovery, she supported microbiologist Dr Sean Simpson (featured in NZ Life & Leisure, issue 36) of Lanzatech in the biofuel firm’s early stages. A desire to grow New Zealand’s science economy is one of the reasons she’s stayed here to launch her own firm.

“I worked in government departments for many years, and I got sick of inventing things and not having them commercialized. In academia I found I wasn’t interacting with the real world or solving real people’s problems.”

Iona began developing Atopis when her daughters were young, turning their playhouse into a makeshift lab. She used compounds found in native trees growing in her garden, including pollen extracted from that rewarewa tree. A few “accidental explosions” drove Iona to establish a proper lab in Rosebank with a small team of scientists who have one thing in common – they are all women. Specifically, working mums.

“An all-woman lab, hell yeah. If you show up in the school holidays, we’re not there, and sometimes the mums bring their kids to the office. It doesn’t affect our work at all, and it’s important to me to make a working environment that’s healthy for female scientists.”

She says this is a reaction to working in government research for many years, an employment environment that wasn’t good for women. “I eventually realized the only way I was going to be able to have children and keep my career was to form my own company.”

Iona commandeered her daughters’ playhouse to create a lab. A few explosive experiments later and it’s now a storage room for Chris’ train gear.

Early in her career at one Crown Research Institute, Iona overheard a senior scientist ruling her out of a PhD placement with the remark, “Well, we can’t choose her, she’ll probably go off and have a baby.”

Together, Iona and an outraged female colleague created a false medical report stating Iona had fertility issues. They placed this in an envelope on her desk.

“Low and behold, two weeks later I was given the job, and it was clear they had looked through the envelope. I can’t believe I had to do that.”

Her employer did not notice Iona had never signed the employment contract that had a clause binding her to her job, just in case she wanted to be a breeder (she did).

The kitchen looks out onto the Manukau Harbour and a small creek that runs through the bush.

It wasn’t a one-off incident. In another job, she learned that all her male colleagues were being paid more than she was despite their identical qualifications and that her male assistant earned 25 per cent more than she did. “I realized I had to value myself as no one else ever would. I vowed never to undersell myself and I’ve had many men tell me I’m overpaid.”

In another role, she got told off by HR for making fun of her male co-workers.

“If I wore a skirt and a top it would get commented on by the men I worked with. Every day they talked about my appearance. Back then some of them wore long socks sandals and paisley ties, so one day I decided to show up dressed exactly like them. They didn’t find it funny.”

There are acts of rebellion throughout Iona’s life but usually they are very logical. She married Chris at 20, while they were both at the University of Canterbury (Chris studying political science and psychology and Iona biotechnology and biochemistry). The pair braved the Christchurch winters living in a caravan but left university with money in the bank.

She has a mischievous look on her face when describing her family’s ice cream fanaticism. The family freezer is filled with ice cream and when they gather to watch their favourite television show 7 Days, Iona, Chris and the girls each have their own flavour.

“I know I work in the health industry, but if you want to eat a tub of Movenpick, knock yourself out. Life should be fun.”

Both Siannah and Tesscinta have shown abilities in science – for a school project, Siannah modified a pregnancy testing kit to test for contaminated cooking oil – but Iona wants them to be creative and is careful not to push. What she will do is try to build an industry that supports women to have careers in science, and she’s pushing for change in the way science is taught in schools.

“I have been talking to politicians and schools about ways to give girls the chance to do more hands-on experiments. Boys often push girls out of the way; we need to change that.”

SMALL WONDERS

Microbial medicine, or the study of how bacteria and microbes affect the human body, is one of the most cutting-edge areas in healthcare. Skin conditions such as eczema and acne are often the result of an imbalance of skin bacteria. Iona’s product Atopis is a prebiotic, which helps the body generate its own healthy bacteria on the skin to regulate the production of oil and reduce inflammation. Similarly, Phloe is a prebiotic (as opposed to a probiotic, which is a live culture of bacteria) and encourages the body to produce its own healthy bacteria in the gut. These products evolved from Iona’s groundbreaking PhD where she was first in the world to prove that programmed cell death (a process called apoptosis) occurs in plants as well as humans. In humans, apoptosis (which means “leaves falling off a tree” in Greek) is how the body eliminates cells that are no longer needed. With a Marsden Fund grant, Iona proved that, unlike animals, apoptosis in plants is reversible, i.e. plant cells can regenerate after being damaged from droughts or disease. Chemotherapy drugs, which are derived from plants, use apoptosis to kill cancer cells. Iona’s earlier work with Kiwi Crush and Phloe stemmed from research into how health supplements reduced or enhanced the effectiveness of chemotherapy drugs.

atopis.com

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.