How French Anduze potter Yannick Fourbet followed his heart to set up shop at Central Otago’s Domaine Rewa vineyard

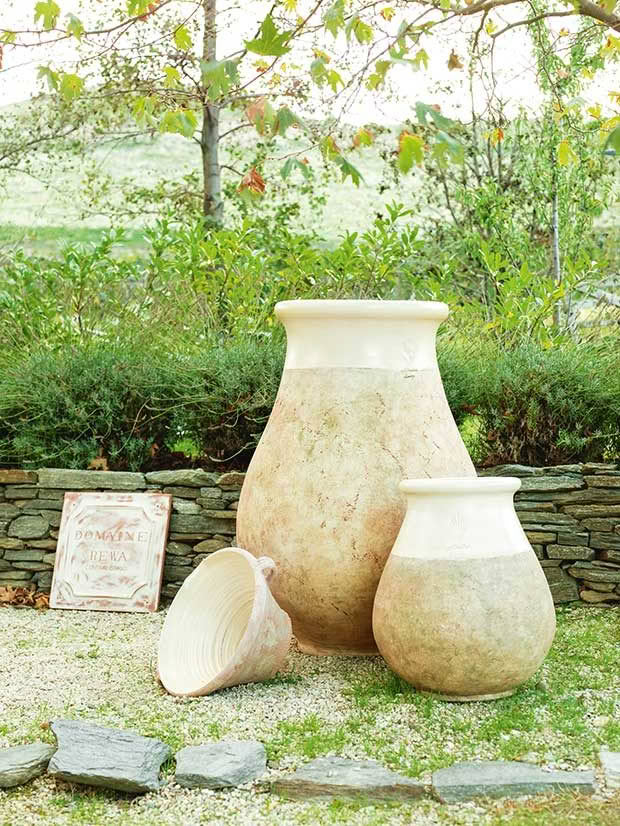

Yannick Fourbet, aka The French Potter, with a variety of rope-coiled pots shipped in from his Anduze workshop, Le Chêne Vert.

When a French Anduze potter met Domaine Rewa, a vineyard-owning investment banker from the opposite side of the world, they discovered their talents and tastes were sublimely matched.

Words: Lee-Anne Duncan Photos: Rachael Mckenna

The house is built as a French-style ‘cadole’ which is a stone shelter for vineyard workers. It was already in-situ when Philippa bought it in 2010, well before she met Yannick. “When I first came here in 2014, and saw this place, I thought, ‘Wow, this is just like a French house.’”

It’s fair baking in the Lowburn Valley. The long view from Domaine Rewa, a vineyard in the foothills of the Pisa Range, is an undulation of beige with a slash of Lake Dunstan’s azure, preceded by ribbons of green vines flourishing into fruit. The extreme heat has banished all thoughts of barbecues, but is accentuating the area’s beauty – so long as you’re not a vineyard worker busy netting grapes against avian invasion.

“An old man told me it hasn’t been this dry for 70 years,” says Philippa Fourbet, the vineyard’s owner and mother of the two little boys at her knee, a little damp from sleep and rosy with summer. Motherhood is Philippa’s latest preoccupation although, as the owner of Domaine Rewa, bought sight unseen in early 2010, she argues she’s been ‘mother’ to a very demanding and costly child for eight years already.

Yannick and Philippa Fourbet and their two-year-old fraternal twin sons, Augustin and Mortimer. Names are important to Philippa – ‘Domaine’ is for her French connection and ‘Rewa’ for her grandmother. For the boys, ‘Augustin’ was a name they both liked, while ‘Mortimer’ has been in Philippa’s family for five generations.

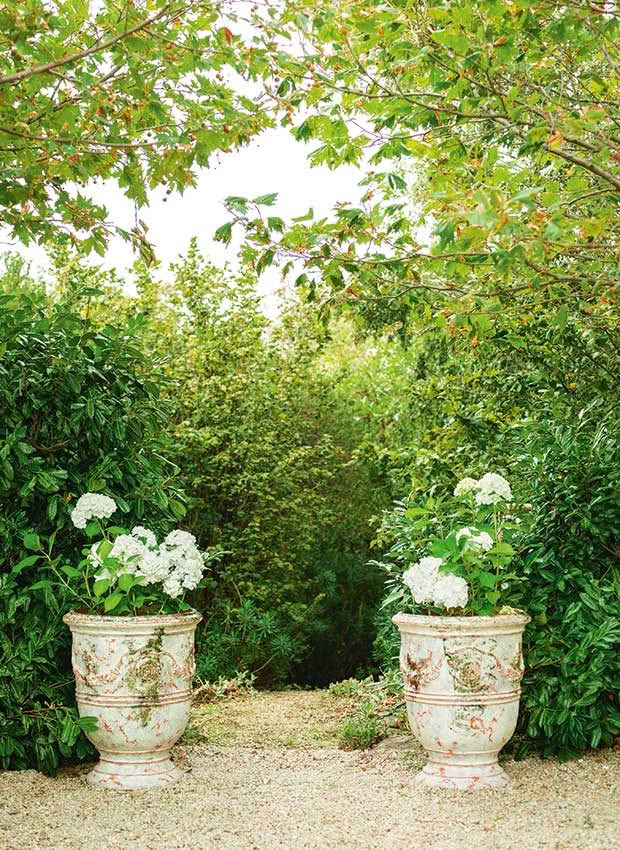

The two-storey schist home on the property is surrounded by swaying plane trees, crunching gravel and blazing lavender, a scene redolent of Southern France. Nothing sings that story more than the plentiful Anduze pots providing pops of pigment against the Central Otago dry.

A native of Waitahuna – a tiny Otago town near Lawrence – Philippa is stylish in the heat, beautifully dressed, quick of speech and wit. Which is perhaps what you’d expect of someone who has lived overseas for 15 years, working as an investment banker mostly in London, and traveling the globe.

It was during a year off to see Europe she became acquainted with decorative French Anduze pots – and the man who made the best. “She fell in love with my pots before she fell in love with me,” says Yannick Fourbet.

Philippa Fourbet delivers lunch under the shade of the plane trees that allow the family to escape the blistering Central Otago heat at Domaine Rewa.

Philippa’s husband is the very image of a French man; he’s hale, hearty, charming, and likes his wine. And he’s actually from Cameroon. “Born and bred, but schooled in France from 15.” At 19, he decided to see the world; he decamped to California’s surf beaches where he learned English and worked in bars to stay afloat.

Then, interested in the sea, he took a degree in marine biology but soon realised lab life wasn’t for him, so he moved into marketing, completing an MBA. When cigarette company Phillip Morris offered him a job sourcing tobacco in Rwanda, he took a U-turn.

Augustin and Mortimer escape onto the cadole’s forecourt.

“This was 1994 and on the radio I was hearing the news about the Tutsis and Hutus. So, no, I decided to go back to France to start a business restoring and selling antiques.”

Anduze pots were originally created as portable planters for citrus trees so they could be sheltered inside over winter. “They are highly decorative and highly functional. People buy them and look after them. They’re built to last for generations,” says Philippa.

Among those antiques were Anduze pots. These clay planters have been used since the 17th century, originally for citrus trees so the precious plants could be moved to over-winter in one’s orangery. They were built to last.

“In France there’s a notion of transmission from one generation to the other; the house stays in the family, and so do the pots. Some families add their own coat of arms and emblems to the pots.”

Mortimer and Augustin play on the daybed on the mezzanine. The antique furniture, including a Louis XV caned bed from And So To Bed in London, melds with the cadole’s old-world French style.

Having learned to restore them, Yannick wanted to make them. He bought shares in Le Chêne Vert, a horticultural pottery in the town of Anduze, in the Cevennes region. Most Anduze pots are made in a mould; as they turn on a wheel the clay is pressed up inside the mould. But one day in a pottery market, Yannick saw something fascinating.

“I met an old farmer whose passion was horticultural pottery. He had beautiful clay on his land and was making pots using an ancestral rope-coil technique.”

Yannick helped him out, carried his clay and brought him water when he was thirsty. “And then I asked if he would mind showing me how to do it. He said, ‘Because you have been kind to me, I will show you.’”

While there are half a dozen Anduze-producing potteries in the region, Le Chêne Vert’s rope-coiled pots stand out. Over the years, Yannick has developed unique glazes that dazzle with colour or replicate the muted hues of a long-lived and loved antique. With the rope’s imprint still visible inside the finished pot, they’re verifiably handmade. “My pots are not a barcode product.”

Philippa first visited the pottery while traveling around Europe with friends in 2009. She looked at the pots and thought, ‘Oh god, they’re so beautiful. I have to come back.’ It took three years for her to return but she did, looking for pots for her vineyard.

“When I arrived on a blistering hot day they were bloody well closed for lunch – so French – so I had to return later. I started quizzing a staff member, but they spoke only rudimentary English. I spoke only rudimentary French, so they went to get the owner.”

“I come out with clay in my hair, in a dirty apron and terrible T-shirt,” says Yannick. “And I see this girl, like sunshine, with a beautiful smile.”

Philippa was keen to import Le Chêne Vert’s pots, so they exchanged emails and communicated for a good six months about how to get the pots to New Zealand – nothing more. When Yannick traveled to the Chelsea Flower Show to exhibit in 2013, which he has done for six years in a row, he sent Philippa a text inviting her along. “We met for dinner and…”

Over the course of the next three years, the couple married but continued to live separately in France and London. “Philippa already had the vineyard, and when I first came here in 2014, I saw this place and thought, ‘Wow, this is like a French house,’” says Yannick.

When Philippa became pregnant with the twins, Mortimer and Augustin (fraternal, but so perfectly matched they’re near identical), she moved to the French countryside. “I’d never lived with a man in my life. And now I’m seven months’ pregnant, living with a man in a foreign country, in the absolute boonies.”

She continued to administer Domaine Rewa, visiting New Zealand for holidays. “I’ve always said I was never going to be an old lady overseas. We planned to come back when the boys were about 10, but in 2017 decided we might as well get cracking. I wanted to be closer to the vineyard and to go back into banking, which wasn’t going to work in rural France.”

Yannick, too, was looking for a change. His family now owned Le Chêne Vert and his bespoke pots were in demand by the likes of Christian Dior, the Palace of Versailles, the cities of Montpellier and Nice, and Petersham Nursery in Richmond, London. Yannick would create pots of a specific size and shape, add each client’s motifs or emblems, and sculpt a unique garland.

But running a workshop, with the politics of employees, was wearying. He wanted to set up his own studio at Domaine Rewa where he could devote himself to his customized pots while also importing classic pots from Le Chêne Vert, now managed by his sister. The couple arrived in Otago on New Year’s Day this year.

Creating a bespoke pot, Yannick says, is about getting the right size, shape and colour for the space and landscape. And in our vast landscapes he’s expecting to fire some giants.

“The only limit will be the size of the kiln I can source. Ultimately, I want to make a New Zealand pot, one that you could see anywhere in the world and recognize it. The ideas are still boiling away but I’ve already sculpted a garland, with a koru for New Zealand and grapes for Domaine Rewa.”

And it is at the vineyard that The French Potter will set up. Pots will be made from a sustainable source – which ties in with Domaine Rewa’s philosophy. With the support of her viticulturists, Philippa has achieved biodynamic certification. She always wanted to run the vineyard in a holistic, sustainable manner, but that was about all she knew when she invested in the vines from Aurum Wines.

“I didn’t even see the place before I bought it, but my parents did and told me to do it.” This banker put in an offer from London on a Monday, forgetting about a pre-approved mortgage. The agent replied saying it had been accepted but must go unconditional by the Thursday. “So I did no due diligence. But, voilà – it turned out okay.”

While Yannick is proud of his wife’s ability to grow her vineyard, increasing the yield from 3000 bottles in 2011 to 14000 in the 2016 vintage, Philippa credits viticulturists, Grant Rolston and Gary Ford, and winemaker Peter Bartle.

“Aside from asking Peter to make the chardonnay in an old-world style, I just said to make the wine he loves.” It’s an approach that has worked; the chardonnay keeps winning awards.

Now the couple are putting time into the vines, learning a new trade. Mortimer and Augustin will eventually be able to join in. “It’s so much better to be here, to help out, and join everyone for a drink at the end of the day,” says Philippa. “Coming home was absolutely the right decision.”

MAKING POTS WITH ROPES

Anduze pots come in many shapes and sizes and can be quite plain or highly decorated. The decorations can be hand-sculpted or made in a mould and applied wet to the pot before firing. However, even if they are moulded, such as with the garlands on the opposite page, Yannick often hand-sculpts them further to give each pot a unique look.

Yannick first came to love Anduze pots when he restored them in his antique business. “Antiques gave me the chance to explore glazes and pots, and they brought me to this country to create pots that will be adapted to the lovely backyard of New Zealand,” he says.

While most Anduze pots are made with a mould, Yannick uses a rope-coiled technique that apparently dates from the Neolithic period. He builds a wooden structure around a vertical axis in the shape the customer wants, then coils rope around the wooden skeleton.

Clay is then hand-thrown on the rope and smoothed down. To customize the pots, Yannick stamps or engraves a customer’s emblem, logo or chosen motif. Then he adds other decorations (such as a face or garland) made from moulds and applied wet. When the pot is dry, it’s fired. A liquid glaze is poured over the cooled pot before a second firing to fix the coloured coating.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ANDUZE PLANTERS

Just over 400 years ago a potter in Anduze was inspired by the elegance of the Medici vase to make the first Anduze planter. Initially available only to the very rich, Anduze pots are now found in households And public spaces around the world.

While the traditional Anduze pot is the “real” Anduze, several variations have been developed over the years, many by Yannick Fourbet himself:

Anduze vase: Yannick has made these as high as 140cm and as heavy as 300kg, finished with a detailed garland or décor.

Anduze cup: Squatter version of the pot, ideal on a plinth or at either side of gates.

Biot: Originally made to store grain, it’s a water-drop shape.

Olive jar: Made to store olives; has a wooden lid. Very decorative horticultural planters or use inside as a lamp stand.

Bowl pot: Replicates a round fruit (an orange or cherry).

Totem: Elongated conical shape, statuesque and contemporary. Ideal for corners, to flank narrow entrances,

or inside the house.

Chelsea pot: Devised by Yannick for the Chelsea Flower Show 2011, it’s rope-coiled, conical, contemporary.

Vasque: Created for Chelsea Flower Show 2017 – it’s wide and may be decorated or plain.

BIODYNAMIC VALLEY

Lowburn, where Domaine Rewa’s 5.5ha lies among other vineyards, is a proudly biodynamic area. That’s handy, as it’s easier to be biodynamic with neighbourhood support.

Biodynamics focuses on soil biology (the living things in the soil) rather than soil chemistry (soil minerals), and promoting biodiversity, so Philippa keeps bees

and shares some Highland cattle with her neighbours.

The aim is to create a quality product through the whole farm working together, rather than individual interventions such as sprays or medicines. Decisions are made through observing and analyzing what suits each property, deciding the best time to plant, prune, harvest.

Biodynamic preparations stimulate biological activity and much of the vineyard’s waste is reused via composting. “I don’t want to be part of the throwaway culture,” says Philippa.

OTHER STORIES YOU MIGHT LIKE

How Karen Rhind started again with a lavender farm and dry garden in Central Otago

How the southerly winds inspire Mark Hill’s amazing sculptures

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.