Waitākere artist Mandy Patmore paints a brighter future for young creatives

Mandy Patmore with husband Markus Ashton. George, a german shorthair-lab cross, is the eldest of the couple’s three dogs.

An environmental artist, dipping into her palette of life experiences, is painting a brighter future for young creatives in West Auckland. It’s her most powerful work yet.

Words: Cari Johnson Photos: Tessa Chrisp

Mandy Patmore had no idea what she was doing. She had been invited to propose a design concept for a footbridge after some well-meaning Piha locals had babbled to the Waitākere City Council that Mandy was darn good at painting.

At the time, she was 26, had “totally sucked” at art school, and hadn’t done much in the way of art since becoming a mum to two sons, Ezra and Lukah.

“I told the council they had the wrong number,” says Mandy, an artist and educator based in Karekare, just down the road from Piha. It turns out the council didn’t have the wrong number, and Mandy did end up submitting a concept for the Piha Domain footbridge in 2008.

- Bronze eel motifs appear to wriggle across the footbridge at Piha Domain, illustrating the various stages of the freshwater creature’s life. Mandy’s S-shaped bridge concept, inspired by short and long-finned eels, was brought to life with the help of TSE Group and Fort Projects.

- “The bridge crosses a migratory route, so it’s a significant message at a significant place. The curved part of the bridge creates a space to soak up the environment — it’s not about being a quick journey across the water.”

- Mandy seldom discloses the Local Hero medal she won at the 2020 Kiwibank New Zealander of the Year Awards — one must unearth it in her home instead.

When she was stuck for ideas, a friend suggested the squiggly shapes in her sketchbook looked like eels. Eels, you say? Mandy took to her laptop to discover her new freshwater friends were in decline due to pollution, dams, and other human activities.

Get Mandy talking about eels or any enviro-related topic, and the flicker that fuels her creativity becomes a wildfire. “I wanted to tell everyone about eels. That’s when I realized you could spread messages through art. You know those religious people who shout on a street corner? That doesn’t work. You’re just going to piss off people. But if you can creatively deliver a message, it works ridiculously well.”

Long-time renters Mandy and Markus couldn’t believe their luck when some neighbours offered them a bush-covered section in Karekare for a bargain. “I think they felt a bit sorry for us,” says Mandy. Between his building expertise and her knack for thrifting, the couple built and filled their 220-square-metre bungalow entirely from scratch. “The house should have a ‘sponsored by Trade Me’ sign out front because that’s where I bought everything.” Mandy first found the kitchen windows for $300, which ended up dictating the design and shape of the home. “But when it started getting built, I was like, ‘Oh my god, it’s huge’. We had been living in a humble shack for 10 years, and I thought we were going to look like wankers.”

These were the thoughts that led to Mandy’s eel-shaped bridge design, intended to educate locals on the ancient creatures swimming in Piha Stream. It won the council over, was erected in 2009 and scooped up Outstanding Project at the New Zealand Recreation Association Awards. Mandy insists the design was an accident.

What isn’t accidental is how she soaks up the world like a parched sponge. At 20, in no rush to begin adulthood, Mandy raced off to the South Island with a guy she barely knew for a summer of partying (having just returned from hitchhiking around Australia).

There, she locked eyes with her now-husband Markus Ashton at a party in Golden Bay. “He was just a hot guy. And then suddenly there was a baby,” she says. Mandy describes her younger dreadlocked self as “a bit feral” and unanchored. Motherhood anchored her and set her off in a new direction.

- The kitchen windows and deck are at arm’s length from the native bush — the latter being a favourite gathering spot for Mandy, Markus, mixed-breed Beau (left) and fox-terrier Koda (front).

- First-time grandparents Mandy and Markus are tickled when son Ezra, daughter-in-law Aimee and eight-week-old Marlee drop by.

“I wanted to be a role model for my kids; I wasn’t going to have anybody judge me. I made a real point in educating myself in the ways of the world. I went to teachers’ college and learned te reo Māori. I just soaked up everything,” she says.

When the Auckland Council hired her to teach kids about the environment using art, Mandy wasn’t yet an environmental artist. There is nothing like alarming facts about water quality and deforestation to get this creative fired up.

“Oh, man, did I learn some stuff? Once you know something, you can’t unknow it. Even if it’s awful, you can’t give knowledge back,” she says.

Mandy’s self-portrait, Reminder, was inspired by the time she got smacked in the head by a ruru (morepork). “When I mentioned this to a friend at work, he went quiet,” says Mandy. Unfortunately, she interpreted this as a sign she or her family were in danger — and thus avoided her car and kept her sons from swimming for weeks. When she informed her colleague of their survival, he laughed. “He hadn’t meant it like that. [The ruru] was more of a metaphor for rebirth, or checking yourself.”

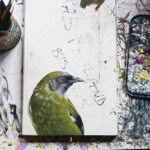

‘The cheerful song of a tūī, perhaps?’ Off she went to her studio and, imagining the scraps as native trees, brought life to their limbs with her paintbrush. She painted native birds.

“When I ‘beautified’ the wood and called it art, it suddenly had value again. I became interested in the perception of value. People will suddenly value it when you put something on a gallery wall and call it art. I suppose it was all a commentary on the value we put on our environment,” she says.

- Markus made the hanging cedar lampshades as a birthday present for Mandy. Dude, another street art-inspired piece by former student Tory Whiting, hangs above the kitchen doorway.

- An eel has moved into the naturally bath-shaped plunge pool facing Mandy and Markus’ home. “I got in the other day, and the little guy was like, ‘Hey, I live here now’,’” says Mandy, who is still trying to become at ease with his presence.

Over time, her timber paintings and multimedia installations became sought-after. However, prominence and creating art for its sake has never been sufficient for Mandy.

After six years at the Auckland Council, she learned this when she stepped into an education manager role at Corban Estate Arts Centre in Henderson. She loved it but felt like she wasn’t doing much to heal the planet or its people.

Until one day in 2013 when Mandy received a call from a police officer. They had a kid who was in trouble but was interested in art. Did she have a suitable programme? She didn’t. More police ended up calling, then social workers. “After getting one too many phone calls, I just went, ‘bugger this’,” she says.

Not for the first time, Mandy has no idea what she’s doing. Truthfully, she has just scraped together $5000 in funding and is winging it as the sole tutor of a nine-week youth arts’ programme. On the first day of class, a nervous Mandy arrives with a lesson plan and three back-ups in case they all flop.

Kōkako on rimu.

Her first four pupils, primarily kids with past offences for theft or vandalism, aren’t too keen on structure. “They immediately go in different directions. One student starts tagging the walls with spray-and-wipe, so I’m like, ‘Cool, let’s put some ink in it.’

I chuck a big piece of paper in front of him and say, ‘have a go with that’. Another is smashing something he’d made with clay. I give him more clay and a meat cleaver and tell him to keep going. We end up selling that sculpture for, like, $80.”

For most of her life, Mandy has used art to make the world a better place. This programme, which she named Kākano Youth Arts Collective, was no different. Kids who were otherwise enemies on the streets became friends in the studio.

Knick-knacks, heirlooms, student artwork and “a little bit of hoarding” comprise most of the home’s décor. Mandy bought the 19th-century printing press (originally from Scotland) years ago from a friend in Northland but didn’t assemble it until boredom struck during a lockdown. “It hasn’t left the dining room because it’s too heavy to move,” says Mandy. The graphic artwork above the chair is by Tory Whiting, a former student at Kākano Youth Arts Collective. Next to it hangs a cast glass jet plane by Simon Ward Lewis, an artist for whom Mandy’s son Lukah worked as an apprentice.

Many discovered more than their niche in paint, clay or ink — they found purpose and mana. Thus, Mandy applied for more funding, quit her job as education manager, and took on Kākano with gusto.

Mandy has never been one to abide by the rules totally, and in the early days, her wholehearted approach to helping students outside the studio took a toll on her personal life.

Social workers are trained to keep firm boundaries with clients; meanwhile, Mandy carted students to and from class in her car, invited one over for Christmas and even convinced her aunt to register as a foster carer. “When you’re locking up the studio for the day, and there’s a kid sleeping outside — what are you supposed to do?”

Kākano students can work on either personal projects or commissioned works.

Eight years later, Mandy finds immense satisfaction in being an artist, educator, street-art creator and mother-like figure to many. She’s learned to celebrate the wins, such as students heading off to art school or onto full-time jobs in the arts.

But, no, she can’t solve every problem facing her students, and a few have ended up in prison. “You can’t win them all,” she says. “But we’ve seen the most incredible changes. The model works because we love them.”

Mandy enjoys painting on timber and printmaking with woodcuts — and sometimes combines both.

In 2020, Mandy was awarded a Local Hero medal in the Kiwibank New Zealander of the Year Awards. Oh yes, that little thing. “Sometimes, I look around and think, ‘Look at all these people I’ve suckered into believing I’ve done a thing.’ They don’t realize I’m a fraud. It feels like I’ve created this whirlpool and just pulled everyone in,” she says.

Mandy still maintains she has no idea what she’s doing. But she certainly knows where she’s going.

OUTSIDE THE LINES

Kākano Youth Arts Collective, founded and directed by Mandy Patmore, was set up for young creatives with offending backgrounds in West Auckland. Kākano translates as “seed” in te reo Māori, and the initiative is named to give students a safe space to take root and grow.

Since its launch in 2013, funding has enabled Mandy to hire three other tutors, a van driver and a youth support worker to help students navigate any issues they may be facing. These days, the only prerequisite for admittance is that the child is not in school.

The Ibis Budget Auckland Airport Hotel recently commissioned the collective’s mural business to design a mural for each of its five storeys. “When the elevator door opens, there is an illustration of a native bird and the floor number,” says Mandy.

Thrice-weekly studio workshops keep the young artists (ages 12 to 20, roughly) creatively engaged and, in the best cases, heading off to a bright future in the arts. “When a student goes off to study or work full time, they’re often the only one in their household doing that. It has a knock-on effect — and you can break a cycle. It’s amazing how transformative the model is.”

Students are also paid to run Kākano Gallery and their own mural business, with past clients including KiwiRail and Auckland Council. Mandy, meanwhile, enjoys playing detective to track down Henderson’s up-and-coming taggers to offer them a job at the mural business.

In February, Kākano Gallery opened its new, larger space in Henderson’s town centre, central Henderson. Open Tuesday through Saturday. kakanoyouthartscollective.com

WHAT IS ENVIRONMENTAL ART?

Mandy describes her artistic “niche” as making people think about environmental issues and, ideally, act.

“You can raise all the awareness you want, but if there’s no action, then it’s pointless.” She grapples with the issue in her art, which she prefers not to make for beauty alone.

- Korimako painted with acrylic on kauri timber.

- Prints from her exhibition Preservation were created with hole-riddled pieces of tōtara brushed with printing ink. The native birds were painted on afterwards.

- Ngā Tuke, te reo for rock wrens, features the birds in acrylic paint.

- This native fauna-rich woodcut is pressed in two colours to create a circular, limited-edition piece called Te Ao.

“It’s shifted a bit too far into beautification. People buy it because it looks nice, but that’s not what I’m trying to say. There’s a real tension between painting things that people will buy and wanting to convey a message,” she says. mandypatmore.com

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.