The ultimate guide to biosecurity on a lifestyle property or farm

Good biosecurity will save you money and heartache.

Words & images: Ross Nolly

My shadow is a Dorking cross hen I shouldn’t have bought on Trade Me. If she sees me when she’s at the end of the paddock, it’s neck stretched out in a 100m sprint to come and say hello. Like all Dorkings, she’s a chatterbox.

When I saw her photos in the advertisement, she looked great. But when I arrived to pick her up, it was clear the photos were old. She was thin and had been pecked bare by the other birds in the flock. Her comb was pale and shrivelled. She looked haggard.

I should have walked away from the sale, but I didn’t have the heart after seeing her condition. I took her home and put her in a run separate from my flock for a couple of weeks.

She turned out to be a great layer, and has more than repaid me with her company, let alone any productivity. But looking back, I made several mistakes. Firstly, I shouldn’t have bought an obviously unwell bird and once I did, I should have kept her separated for longer to prevent her from passing parasites or diseases to my flock.

- Before: This is the Dorking hen I shouldn’t have bought off Trade Me, looking unwell and haggard.

- After: The same hen, three years later. She follows me everywhere, steals food off my plate at the picnic table, and has more than paid me back in egg production, and fun.

Biosecurity on a farm or lifestyle block is an easily overlooked, but important issue for any livestock owner. Most people understand the need to stop unwanted organisms such as weeds or animal pests establishing on their property. But biohazards such as a disease or parasites can’t be seen or as easily controlled.

Good biosecurity minimises the chance of something spreading through your livestock, around your block, and to neighbouring properties.

Most of NZ’s professional agriculture industry was blasé about biosecurity for a long time. Lifestyle block owners were even less aware or unfamiliar with the concept, especially those who had never farmed before.

But the Mycoplasma bovis outbreak in 2017 was a costly biosecurity wake-up call to everyone who has cattle and will continue to be for the next few years. Sadly, many people learned about the value of good biosecurity the hard way, financially, and emotionally.

Animals that pass through stockyards are at risk from disease and pest exposure.

Good biosecurity means identifying hazards to prevent new, unwanted organisms from coming onto your property. There are always going to be diseases such as E coli and diarrhoea-causing viruses on any farm or block, no matter how careful you are. Every animal, however carefully you drench them, will carry a worm burden.

But your livestock won’t have immunity to a new disease or parasite. These may cause severe symptoms or death in stock, and be very difficult to eradicate without completely destocking and starting again.

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, and it’s never truer than when talking about farm biosecurity. A lack of precautions can lead to sickness, death, high vet bills, and long-term, ongoing control costs.

If you have stock with an infectious, incurable disease, especially rare breeds, it will restrict (or prevent) the sale of your stock. Depending on the disease, you may be able to sell to farmers with the same problem, but often you’ll need to cull affected livestock if you want to eradicate it.

It’s not pleasant to see animals become ill, or euthanising them, especially if it’s multiple animals you’ve hand-raised, or work with closely. For example, Johne’s Disease is caused by a highly infectious, incurable bacterium that can show no symptoms for months or years in goats, sheep, cattle, and deer. Once there are symptoms, it’s fatal.

Asymptomatic stock shed it through their faeces. Only a tiny amount (less than ¼ tsp) needs to be ingested for an animal to become infected. It’s usually young, more vulnerable stock who taste-test things they find on the ground.

It’s an ongoing management issue in large commercial operations, but it can be devastating in a small goat or sheep herd. If you want to get rid of it completely, you need to cull stock and not graze affected pasture for up to two years.

What is farm biosecurity?

Biosecurity is a set of measures designed to prevent the entry, establishment, and spread of pests and diseases on your property.

Three common areas of risk are buying livestock, breeding livestock, or visitors (or you) carrying something onto your property on a vehicle, shoes, or clothing.

The most recent large-scale animal disease outbreak in NZ was Mycoplasma bovis. It causes illness in cattle, including udder infections (mastitis), arthritis, abortions, and pneumonia (but doesn’t affect humans, and isn’t a food safety risk). The NZ government chose to eradicate the disease over 10 years (2021 is Year 4).

The numbers so far (as at May 2020) are enormous:

Farms affected: 58 dairy, 137 beef, 54 other

Where: 68 North Island, 181 South Island

Toll: 154,788 animals culled

Famer compensation: $149.3 million

LESSONS FROM CALF-REARERS

Calf-rearing is fraught with the risk of disease. Successful calf-rearers are acutely aware of all aspects of biosecurity. Most have a rearing area specifically set aside for calves and young stock.

A modern calf rearing unit. It has a high roof and an open front to maximise ventilation. Deep sand with drainage beneath it helps to keep the bedding dry. Solid barriers between the pens prevent nose-to-nose touching. Each mob has its own feeder.

If an unwanted organism is brought in, it’s isolated to that area, rather than spread throughout the farm. Many calf-rearers use separate milk feed trailers for different mobs to prevent cross-contamination. They also use solid walls between the individual pens to prevent nose-to-nose contact.

What you can learn from professional pig & poultry farmers

Large-scale commercial pig and poultry farms have very high biosecurity awareness and take strict precautions. Their most significant risk is highly infectious, deadly viruses.

INTERNAL BIOSECURITY

• enforced restriction of people between clean and dirty areas/jobs;

• protective clothing is worn in one area, then removed;

• footwear is disinfected, and only used in one area;

• workers must shower when they get to work, and again before they leave;

• worker movement may be restricted between individual sections of the farm – for example, there are workers at commercial poultry hatcheries who never cross paths in their work, and who don’t socialise together, even outside of work.

NZ’s commercial poultry industry is free from some of the world’s worst infectious poultry diseases, thanks to strict biosecurity measures on-farm and at the border.

EXTERNAL

• when new pigs arrive, they are quarantined;

• it’s rare to allow visitors, and even rarer for farmers to visit each other’s properties;

• support vehicles are thoroughly cleaned before entering a property;

• pig farmers always purchase from a breeder with stricter biosecurity than their own, never lower;

• they also take extra biosecurity measures according to the health status of farms they visit, or ones supplying them with new stock.

THE RULES ON PIG FEED

It’s crucial to know the types of feed you can and can’t feed to pigs by law. If you supply food waste for feeding to pigs – either to someone else or directly to pigs on your block – you must make sure:

• the food waste doesn’t contain meat and hasn’t come into contact with meat (meat-free waste can be fed to pigs without further treatment);

• if the food waste does contain meat, or has come into contact with meat, it’s treated before being fed to pigs. Treatment involves heating the food waste to 100°C for one hour to destroy any disease-causing bacteria and viruses.

Read more here: the laws on feeding food waste to pigs

4 practical ways to protect your block and livestock

The greatest biosecurity risk you face is when a live animal comes onto your block. Diseases can be transmitted through saliva, milk, and colostrum, in utero, and via artificial insemination. Others can come in on cars, trucks, farm equipment, machinery, boots, and clothing.

1. DO YOUR BREED RESEARCH

Whatever animal you’re interested in, find out what the common transmissible diseases are before you buy. Cultivate a relationship with an experienced stock person and learn from them.

Often, it’s people new to farming who are most at risk of buying a problem because they don’t know the right questions to ask.

For example, if you’re interested in goats, you’ll want to know:

• the seller’s testing regime for infectious, incurable diseases such as Johnes and CAE for their whole herd (not just the animals for sale);

• when were tests last carried out – ask to see the results;

• if the animal you want to buy is under a year old, look at the mother’s test results (as testing for Johnes and CAE isn’t accurate in young animals);

2. SECURE YOUR BOUNDARY FENCES

Good fences limit contact between your stock and any neighbouring animals. Some diseases are transmissible when animals interact along a fence, eg touching noses, licking.

Consider having outriggers with electrified wire or a second internal fence to prevent animals from touching each other.

3. FIND A GOOD VET PRACTICE

Form a good relationship with a local vet practice with staff who are knowledgeable about your animal species. A good one will happily point you to someone else if they don’t have the right expertise.

4. PRACTICE GOOD STOCK MANAGEMENT

Good farm hygiene and animal husbandry are essential. A nutritious, balanced diet and clean, spacious conditions help to keep stock robust and healthy, and better able to cope with exposure to disease or parasites.

Crowding, poor hygiene, and lack of access to food and clean water create stress in animals, which can reduce their immune response. Overstocking is common on blocks. It can be difficult to judge ideal stock numbers, especially during and after a severe weather event, eg drought, flooding.

Besides stress, overstocking concentrates unwanted organisms in an area. Even if all you have is 3-4 hens, they need separate runs so you can rest an area to prevent pasture and soil damage, and the accumulation of manure and parasites.

3 good reasons to quarantine new stock

When you bring new animals onto your property, place them in a quarantine area for a time, away from your other stock. Ideally, yards and quarantine areas for sheep, cattle, goats, and other large livestock should be as close to your front gate as possible.

New animals should be at least 3m away from resident stock. Ideally, graze your resident stock as far as possible from the quarantine area.

You don’t want to risk a long-term breeding project by accidentally importing an unwanted organism, especially if you have a rare breed, such as these White Galloways.

There are multiple benefits to quarantining stock:

1. You prevent any new organisms from entering the main grazing areas.

2. You can easily watch the new stock for signs of illness, which can be triggered by the stress of transportation and being in a new environment.

3. It reduces animal stress, so they get time to rest before they’re stressed again when you introduce them to your main herd or flock.

QUARANTINE TIMING

Pigs: 6-8 weeks.

Poultry: 6 weeks,

drench every two weeks.

Sheep: at least 4 weeks.

Cattle: at least 4 weeks.

Goats: at least 4 weeks.

Horses: at least 3 weeks.

WHY YOUR EYES ARE YOUR BEST MANAGEMENT TOOLS

When you get to know your animals well, you’re likely to get a ‘gut feeling’ when something isn’t right. Often, it’s a subtle difference in the animal’s body language that’s difficult to explain in words.

One day, my kunekune piglet Willow didn’t seem quite ‘right’ to my eyes. She didn’t look sick, but I had a gut feeling and rang the vet, apologising in advance in case it was a wild goose chase.

The vet found she was in the early stages of an infection. A couple of days of antibiotics, and she was back to her usual precocious self. Today’s she a rambunctious, happy adult.

It may seem a bit airy-fairy to tell a vet that you feel an animal is unwell. But a good vet never underestimates the importance of a farmer’s intuition. They also prefer to be called out for a false alarm or at the start of an issue, rather than at the last minute when an animal is suffering. Typically, the earlier you call in a vet, the cheaper it will be to treat a sick animal.

ROSS’ TIPS TO DEVELOPING YOUR INTUITION

It’s important to run a critical gaze over your stock, every day, in the same way you automatically check fences, gates, and water troughs. As you get to know your animals over time, you develop a feel for their usual demeanour and behaviour.

Willow as a piglet, a few months before she got sick.Apply the same stock observation skills that you use to assess your stock’s health and wellbeing to any you’re considering buying. Do they look healthy and robust? Do they have a bright eye? Are they in good condition with a curious, bright demeanour?

Why every cow counts when it comes to NAIT

Even if you have one cow, there are good reasons why it needs a NAIT tag.

Words: NAIT

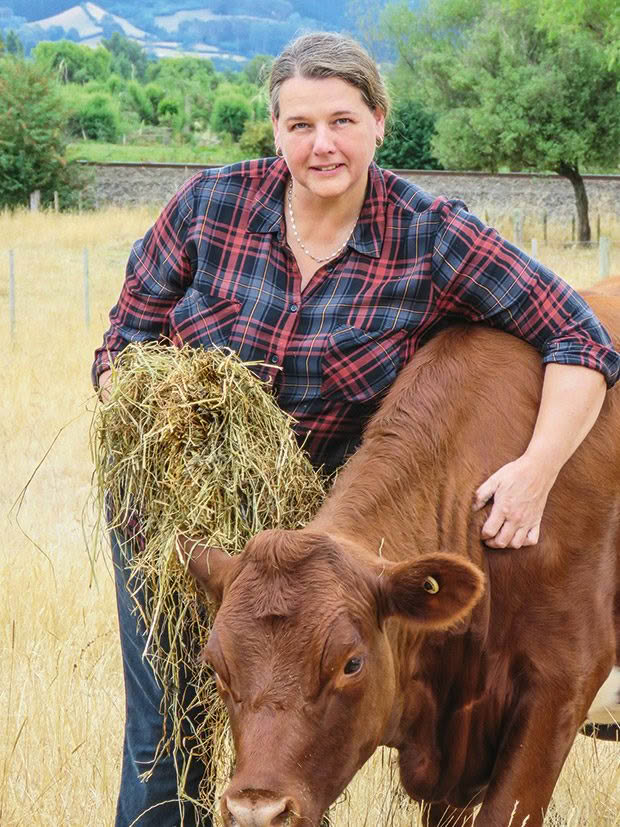

Who: Marnie Rutherford, writer

Where: Carterton, 80km north-east of Wellington

Land: 1.6ha (4 acres)

What: small flock of sheep & one cow

Marnie Rutherford knows the one cow she owns is never leaving her block. When she’s the right size, Marnie plans to homekill her, but her cow still has a compulsory National Animal Identification and Tracing (NAIT) tag clipped into its ear. The NAIT scheme allows for the rapid and accurate tracing of individual livestock, from birth to death, or live export.

“From my experience, most lifestylers are aware of NAIT but may be unsure if it applies to them, and what they need to do about it,” says Marnie. She started the Wairarapa Smallholders Group to help local block owners become better equipped and informed about managing animals.

“Animals on small blocks are often destined for homekill or used for paddock management, so may never leave the property at all. As they’re not part of the commercial food chain, recording them (in the NAIT system) may not be seen as a necessity.”

She says the importance of recording livestock movements doesn’t seem that significant to some lifestylers.

“I think the ease livestock diseases can spread by animal contact through fences is underestimated. It might be as simple as lice, or something much more costly like Mycoplasma bovis, but it’s up to you to take responsibility and look out for your animals and neighbours, even if you only have one cow.”

3 IMPORTANT THINGS TO KNOW

The Mycoplasma bovis outbreak highlighted the cost to farmers by those who weren’t complying with NAIT regulations. If you own even one cow (or deer), you must be registered with NAIT, tag it, and record it in the NAIT system when it moves on or off your block.

If you haven’t used NAIT since early 2019, you will need to re-register. Fines now range from $400-$800+. Read more here.

MORE HERE

What is your chicken trying to tell you? A guide to poultry signals and hen clucks and cackles

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.