The ultimate guide for a sick chook: Vaccinated flocks, dealing with new birds and the case study of a limping hen

Working out what’s wrong with a sick chicken can be tricky, even for an expert. Here’s how to improve your odds of getting a diagnosis, and prevent illness in your flock.

Words: Sue Clarke

If your bird is unwell, your vet or a poultry expert needs to know important details, especially if they can’t examine the bird in person.

Examine your bird, but don’t make assumptions about what you see. For example, you may find a bird limping or bleeding and assume it was due to a fight with another flock member. That may be correct, but poultry often attacks a flock mate showing subtle signs of illness.

The basic details an expert needs to know are:

– age

– breed, eg purebred, cross, hybrid

– sex

– location (if you’re asking an expert online)

– current diet, including access to plants, scraps etc

– routine health regime, eg worming

– type of housing, eg coop and enclosed run, coop with a free-range

– symptoms, eg limping, panting, signs of discharge from eyes or nose, colour of face/wattles, coughing, lice or mites on skin, twisted neck

– breath rate per minute

– temperature

– demeanour, eg depressed (not moving, hunched, eyes closed)

– droppings, eg colour, consistency

– appetite and hydration, is it still eating and drinking

– mobility, eg activity level, is it limping, falling over, unbalanced, are its legs in odd positions, is it paralysed?

Sue’s tip: Take photos and video of a sick hen, including clear, in-focus close-ups of its face and vent, and any symptoms it’s showing, especially if they’re intermittent, eg coughing, panting, limping etc. It will be of great assistance to an expert if they can’t see your bird in person.).

WHAT TO DO IF YOU HAVE A SICK CHICKEN

1. Immediately isolate it from the rest of the flock, mainly to prevent it from being bullied by others, and to prevent any possible diseases from spreading.

2. Keep it in a quiet, warm, draft-free place, eg in a cage or large box in a garage or barn.

3. Monitor the bird, including its droppings, and note any symptoms and if they’re worsening;

4. Offer it electrolytes, mixed in water.

5. Have its regular feed available, plus little morsels of fatty, high protein food such as dogroll or cat jellymeat (which can stimulate the appetite and help with hydration).

6. Get a diagnosis as soon as possible, and treatment if available. Depending on the cause, eg gapeworm, coccidiosis, you may need to treat the whole flock, even if the other birds aren’t showing symptoms.

As with any animal, it’s vital to think of the welfare of the bird. A sick or injured bird will hide its pain and distress, but if it’s barely moving about, it’s likely to be in agony.

Don’t leave it for a day or two to see how things go. Get advice and treatment immediately. If symptoms continue to worsen over a day or two, humanely euthanise it.

WHY DO VACCINATED CHICKENS GET SICK?

People are often confused when their vaccinated rescue hens become ill. Commercial layer flocks are vaccinated against several diseases when they’re chicks, including Marek’s disease, salmonella, and infectious bronchitis.

Some farmers also vaccinate for fowl pox, infectious laryngotracheitis (ILT), and egg drop syndrome (EDS) if they’ve had a problem before. A free-range flock is at high risk of contracting all these diseases, which are easily carried in on vehicles, feathers, dust, wild birds, rodents, footwear, and clothing.

Vaccination won’t always prevent diseases. Over time, the immune response lowers if a bird doesn’t encounter the disease. For example, the immunity levels of vaccinated layer hens in a commercial flock slowly reduces, as they live in sheds. When they’re around two years old, you get them as rescue birds. If they encounter something such as infectious bronchitis, they may catch it, even if they were vaccinated against it.

Commercial hens vaccinated as chicks for Marek’s disease may develop the ocular version (the eye turns grey) and go blind later in life. Marek’s normally only affects birds aged under a year, but they can develop the ocular version due to the stress of being rehomed from a warm shed to a colder (outdoor) range, different feed, and a new environment.

LARGE-SCALE ILLNESS OR MULTIPLE DEATHS

It’s vital to get help urgently if multiple members of your flock have similar symptoms, or worse, die. Any suspicious illnesses or deaths, especially when several birds in a flock are sick or dying, should be reported to a vet (even if you have a small flock). You can also phone the Ministry for Primary Industry’s 24-hour hotline (0800 80 99 66) for guidance.

If there’s any sign it might be an exotic disease – that’s a disease not known to be in NZ, such as bird flu – a vet can submit samples to Massey University for diagnosis, a free service.

If you don’t qualify for free testing but still want a diagnosis, several laboratories around the country specialise in disease testing. They need fresh samples and, if possible, sick birds to examine, or blood, faecal samples, and swabs.

A vet can usually submit the samples for you, but you need to tell the laboratory what to test for (eg, antibodies for a virus). Some tests are costly, and it may not be economical for you. However, it can be worth it if you have a large flock and/or rare, expensive breeds.

11 WAYS TO HELP CHICK HEALTH & PREVENT DISEASE

If you own poultry, you’ll have sick birds at some point. It’s not possible to prevent every disease, even if your biosecurity is perfect. Some come in on the wind or are spread by wild birds or rodents.

Chicks hatch with antibodies to several conditions, passed on by their mother, which last for 3-4 weeks. In the meantime, their own immune system is developing as they’re exposed to infective sources in the environment.

When a chick picks up a new pathogen, its immune system produces antibodies to fight it. The chick either creates enough antibodies to fight it off – usually gaining immunity to it – or the disease kills it.

There are things you can do to help chicks develop a more robust immune system:

Keep a hen and chicks, or chicks you’ve hand-raised, separate from the main flock for at least 4-6 weeks.

Provide a dry shelter with good airflow (but not drafty), and a dry, deep bed of litter – wood chips are ideal as they can absorb moisture. Remove mucky or wet patches regularly.

Protect birds from bad weather, especially rain. Don’t allow the run to become muddy – if it does, cover it with a deep bed of litter (eg, bark) or don’t allow them access until it’s dry.

Secure the coop and run (if possible) to keep wild birds out.

Allow all birds 24-7 access to feed and fresh water in clean containers.

Work with chicks and young birds before you work with adults, so you’re not accidentally spreading pathogens.

Use separate equipment for chicks and adults, and wash it regularly with a viricidal disinfectant.

Wash your boots between pens.

Don’t allow visitors who own poultry – if you do, insist that they come in clean clothes, and provide them with footwear.

Regularly clean out hen housing.

If you suspect a disease, quarantine the affected birds immediately, and get a diagnosis.

5 TIPS IF YOU BUY IN NEW BIRDS

New birds can carry diseases to which your flock has no immunity. While they may look healthy, they can be shedding pathogens in their droppings, eg a strain of coccidiosis or salmonella that’s not in your environment. You need to:

1. Quarantine all new birds arriving onto your property for 4–6 weeks.

2. have the quarantine area as far away as practical from your flock.

3. feed them last, so you’re not walking any possible contaminants into your main run.

4. Use a dedicated feeder and drinker in the quarantine area, and don’t re-use it with your main flock.

5. Be meticulous with the hygiene of boots, equipment, and how you dispose of their droppings.

Case Study: The unusual case of the limping hen

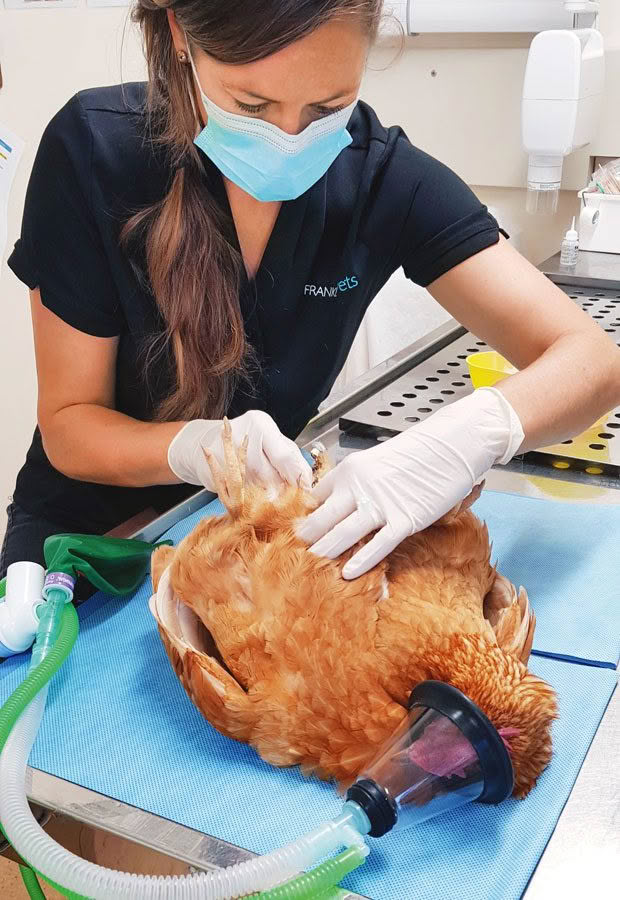

Vet: Sarah Clews, Franklin Vets

Ally was a bright, alert, three-year-old brown Shaver, who developed a worsening limp over a couple of weeks. It’s the sort of case I’m regularly asked to help with, usually online, and often that’s all the detail I get.

If someone asked me about a case like Ally’s, there are a few things I’d need to know before I could attempt – at best – an educated guess, including:

– is the hock joint (the big joint near the top of the leg) hot and swollen?

– is the footpad swollen?

– is there a scab on the footpad?

– is something stuck in it (eg, a prickle)?

– is the bird putting any weight on the leg?

– is it dragging its leg?

– is the leg bent in a place where it shouldn’t bend?

– are there any other signs of ill-health, eg depression, loss of appetite, breathing issues?

In Ally’s case, the initial answer to all these questions was no. Fortunately, her owner had taken her to see South Auckland farm vet Dr Sarah Clews who prescribed anti-inflammatory and pain relief drugs.

However, over the following week, Ally’s limp got worse. Many owners would assume a physical cause for a limp. It might be an injury caused by jumping from a height, being trodden on by other livestock, injured in a fight, or an infection in the leg or foot.

But weirdly, limping can also be a symptom of disease.

Despite medication, Ally the hen’s limp worsened. She was brought back to see Sarah when she developed ascites (fluid accumulation within the abdomen) and started breathing with her mouth open.

Fluid can leak into the abdomen for several reasons:

•internal bleeding;

•cancer;

•reproductive disease;

•heart dysfunction;

•liver dysfunction.

When fluid accumulates in the abdomen, it compresses the air sacs, which can lead to respiratory distress. Sarah did an ultrasound and drained the fluid from Ally’s abdomen, which helped her breathing. A sample of the fluid was analysed.

- Enlarged Bursa of Fabricus.

- Ally the hen seemed to have a simple leg injury. But x-rays showed she had fluid filling her abdomen, an enlarged mass, possibly the Bursa of Fabricius or a cyst, and a thickening of the bone in her leg.

- Her liver contained tumours (the pale patches, above).

There are many causes of lameness. But when a lame bird then develops fluid in the abdomen, it points to a cancerous process. The top possibilities were Marek’s disease and lymphoid leukosis. A leg x-ray showed a dark patch and a thickening of the bone, sometimes seen in lymphoid leukosis cases.

When Sarah operated on Ally, she found pale-looking tumours on the liver, and either an enlarged Bursa of Fabricus (an organ in birds that produces immune cells) or a cyst. Both are also signs of lymphoid leukosis.

Lymphoid leukosis is caused by a retrovirus. Most infected birds only show vague signs such as weight loss, diarrhoea, and lethargy. Others live quite happily, with only a drop in egg production. Even in a heavily infected flock, the incidence of tumours developing to this point is 1-2 percent.

There’s no treatment for lymphoid leukosis. Due to its advanced state, Ally was humanely euthanised.

MORE HERE

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.