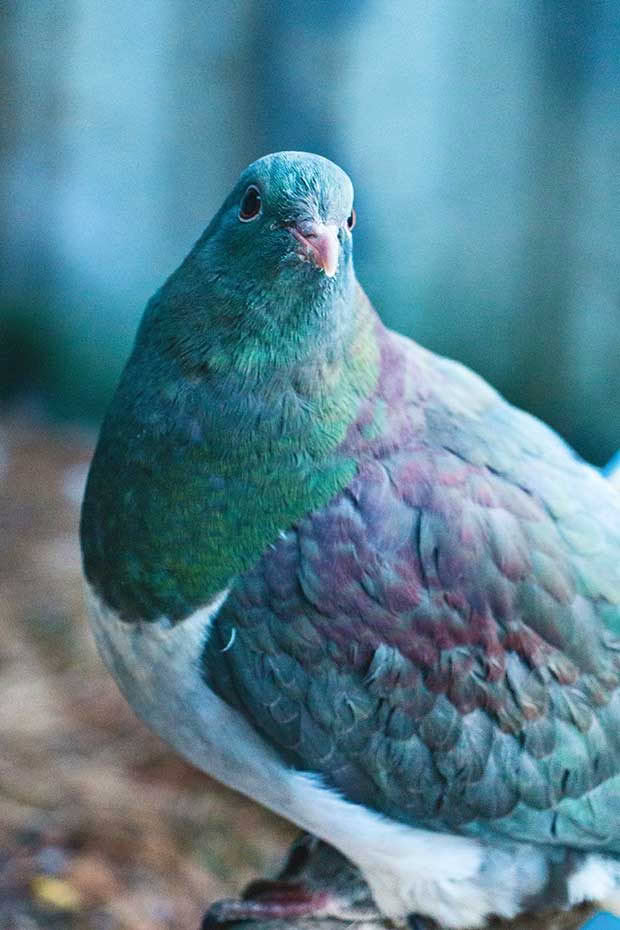

Safe landings: Project Kererū founder Nik Hurring finds her calling by taking in injured kererū

Photo by Nik Hurring.

At 17, Nik Hurring took New Zealand’s most accident-prone bird under her wing. She has been rescuing kererū ever since.

Words: Cari Johnson

In the animal kingdom, there’s no safety net for careless, greedy behaviour.

Kererū can’t hail a taxi after pigging out at a midsummer feast, berries fermenting in their crop, and there’s no one to catch the chick that slips through a hastily built nest — a likely consequence of the bird’s laid-back, “she’ll be right” attitude.

Project Kererū founder Nik (short for Nikola) Hurring embraces the humour of New Zealand’s most accident-prone bird because, otherwise, it’s a bit grim. Kererū, also known as the New Zealand pigeon, are exceptional, she says, and not just for their comical personalities.

“They are incredibly important for seed dispersal. If there were no kererū, some native trees would not survive,” she says.

Nik Hurring.

Nik’s work with kererū began in the 1990s while she was working as a veterinary nurse in Dunedin for DOC. There, the then-17-year-old noticed a pattern among injured birds — a staggering number of kererū.

“You know how people bring their work home? I did that with kererū,” Nik says.

Her home became a rehabilitation centre, which eventually expanded out of the house and into her dad’s shed. By 2002, Nik needed more space. Dunedin Forest & Bird stepped in, funding four aviaries through the Dr Marjorie Barclay Trust.

Still, Nik couldn’t heal them all, with many kererū injuries beyond her expertise. “Kererū came [from DOC] regardless of how badly broken they were,” she says. Euthanasia was sometimes the only option.

Photo by Nik Hurring.

That all changed when Dunedin’s Wildlife Hospital, a one-of-a-kind facility at Otago Polytechnic, was established in 2017.

Today, injured kererū go straight to hospital before being transferred to a Project Kererū aviary, where they remain until they can fly. Once an injured bird has recovered, Nik (or a volunteer) releases them where they were found.

“Wildlife rehab is about second chances. In a sense, I feel some of their freedom when they fly away,” she says. But she keeps her distance — physically and emotionally. Cuddles are off limits, and kererū are named by the suburb in which they were found, not with affectionate pet names.

“I keep my hands off as much as possible. Kererū need to stay wild and keep their natural fear of humans,” she says.

Photo by Nik Hurring.

Even though Nik is now a stay-at-home mum, Project Kererū is still a full-time, voluntary job.

She maintains the aviaries, releases birds and, twice-weekly, checks instant-kill traps (paid for by the Otago Regional Council Eco Fund), which control the pests that can spook the birds.

But with all that has evolved, one thing has remained constant: “The project has never been about me. It’s about the birds and always will be.” projectkereru.org.nz

THREATS TO KERERŪ

Overall, kererū numbers are stable, but the species is in decline in regions where pests and illegal hunting go unchecked.

Rats, stoats, possums (and even cats) eat chicks and eggs. Kererū are poor nest builders, and fledglings can fall through the haphazard construction.

Photo by Nik Hurring.

Their habitat is also shrinking, exposing them to hazards like cars and window strike (see below).

HOW TO HELP

Feed kererū by planting trees like miro, plum or lucerne (tagasaste). Find a full list of kererū-friendly trees at Project Kererū.

Prevent window-strike by keeping bird feeders within a metre of the house or farther than 10 metres from windows.

Birds may attempt to fly through windows that face each other or if a reflection confuses them. WindowAlert decals can help. “They make windows look like a giant stop light to birds,” says Nik.

Report injured kererū to the DOC emergency hotline: 0800 362 468. If DOC is unavailable, Nik recommends carefully picking up the bird with a towel and placing it inside a cardboard box. Keep it somewhere warm and quiet until DOC can help.

MORE HERE:

Lisa Scott tries hot yoga in Otago Museum’s Tuhura butterfly enclosure

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.