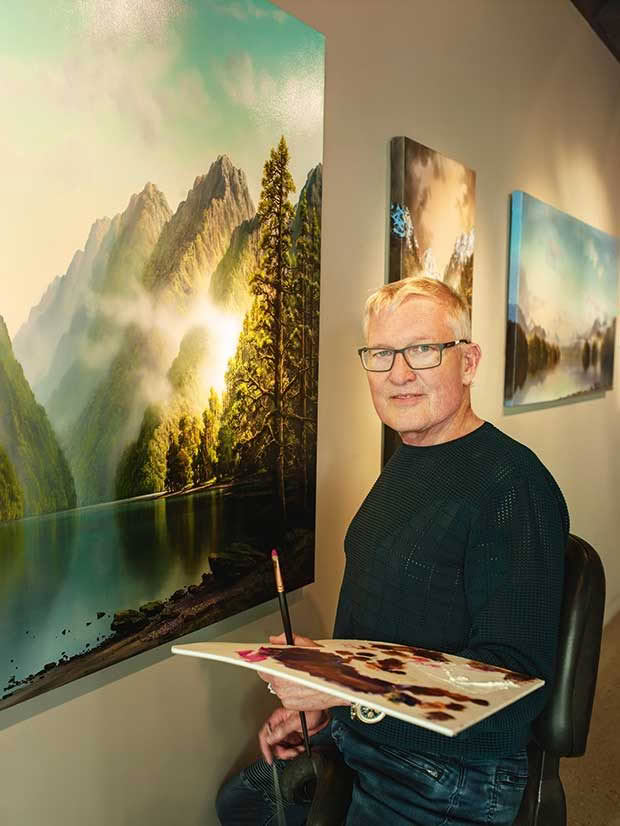

Queenstown painter Tim Wilson celebrates beauty, light and spirituality in his renowned oil landscapes

Tim Wilson’s father was so excited by his son’s first exhibition of landscape paintings he proudly predicted, ‘You know Tim, one day you’ll be getting $1000 each for your pictures.’ He wasn’t wrong.

Words: Kate Coughlan Photos: Rachael McKenna

Editor’s note: Subsequent to publishing this story, Tim passed away after a battle with cancer. The Tim Wilson Gallery is located at 27 Edinburgh Drive, Queenstown Hill. A book about Tim’s life and art is being prepared for publication. For expressions of interest in visiting the gallery or purchasing his book please contact info@timwilsongallery.com

Picture this: A flat-deck truck with builder’s gear on the back lumbers up a road into the Ruahine Ranges behind Palmerston North. It is 1964. From the cab leaps a skinny, blonde, 10-year-old boy twitching with energy. His father follows, and they walk a bit, then sit and stare into the west where the sun melts into the distant Tasman Sea.

“What do you see Tim?” asks the father. “Tell me the colours you see.”

The boy looks closely as fading light falls in a kaleidoscope of shades across the landscape. Carefully, he tells his father what he sees; the clouds are glowing. The language he uses is undeveloped, yet he understands what he’s looking at, it reminds him of the milky opal chips given to him by his Uncle Jack.

He does his best, so he and his colour-blind father (who is unable to distinguish red and green) can share what the other sees and enjoy the glory of light on the land.

The house sits over three levels looking across Lake Wakatipu towards the two peaks of Walter and Cecil to the south.

Today, in a smart gallery in Queenstown’s Beach Street, a wiry blonde man perches on a small saddle stool applying oil paint in intricate strokes. His work illuminates a tiny portion of a two-metre-wide canvas depicting a beautiful landscape. Right by his ear, peering over his shoulder and not a breath away, is a tourist who has just wandered into the gallery.

“What do you see? Tell me the colours you see,” requests Tim Wilson, not at all bothered by the closeness of the stranger. He wants others to experience, as he does, the joy and magnificence of the universe. He wants to share the gift given by his father all those years ago in the hills behind Palmie.

Tim’s husband, Vaj Ekanayake, decided in 2009 that the couple should move from Auckland to Queenstown, establish their own gallery and take control of selling Tim’s work.

“I was difficult as a kid, a dyslexic, everything back-to-front, temperamental, a little shit probably. My dad had an amazing way of calming me down. He would say: ‘Come on Tim, let’s go.’ We would jump into his truck and be off into the countryside. And just look.

“I had a very, very, very colourful, vivid imagination and I was hyperactive. He would call our trips, ‘Soothing the wild beast’, and it worked. I was already painting by the age of seven — and always landscapes. It fed me to be taken daydreaming and looking at the clouds and colours in the hills of the Ruahines and Tararuas.”

Tim’s parents understood he saw things differently, experienced the world in his own way. It was OK for him to be creative. He was the kid who refused to go inside when the family went visiting. Tim had things outside he needed to look at.

“I can feel it even now, 60 years on, Athol Priest’s house — an arts and crafts home in Palmerston North’s Church Street — the conversation drifting out the open window and me mesmerized by the shimmering heat of the day bouncing off a concrete path, a row of tall tiger lilies with the light playing through the petals, the crimson and rust spots of colour and the smell… ahh, the smell.”

His childhood memories are all like this: intense, intimate, detailed. And always about how the light shone and danced, him questioning why it made him feel the way it did. The miracle of the universe intrigued him and still does. It is what drives him outside into the landscape and on starry nights to wonder; it is what drives him to paint.

“We need to talk about spirituality. There is no doubt people are looking for something spiritual, though my painting is certainly not about God as in a hairy fellow with a beard throwing lightning bolts about. I have no doubt there is a power, a force, an energy. Go west into Doubtful Sound and there it is, in this primal cathedral, and it doesn’t get any better anywhere on Earth. Is that spirituality? I don’t know, but it is a fundamental thing for me.”

“Building the house wasn’t an easy project for us to work on together,” says Vaj. “In my world of business, it is important to stick to the spreadsheet and be within budget. But, for Tim, the house was a work of art and cost was irrelevant.”

This perspective has inspired decades of painting since Tim left his trade as a jeweller to follow his heart and heed his dad’s advice — after Tim’s first exhibition of oil landscapes in Palmerston North’s Parlane & Glasgow Gallery — that his paintings would be worthy of a good price someday.

His father wasn’t wrong; he just underestimated. In 2015, the New Zealand record for a living artist ($575,000) was paid by an international collector for Tim’s painting, Summer Rains Doubtful Sound.

Tim says Vaj’s business skills have made it possible for them to market Tim’s work and run the gallery with its team of five staff. For Vaj, there has been a learning curve too. “When I came here, I had no practical skills. I had been working in finance and in large hotels and I knew nothing about cooking or cleaning or even how to use a hammer.”

He’s not much good at name-dropping, but it is public record that his clientele includes the powerful and famous such as United States political royalty, the Kennedy clan, and singer Shania Twain.

Tim’s journey has included plenty of challenges. “I spent years fighting the establishment — the mockery of being a landscape painter — and I produced a lot of crap there for a time. In my young years, I was a larrikin — drugs, sex and rock ’n’ roll, desperately trying to find my way. But always the painting…

Iconic Australian photographer Max Dupain is represented with two photographs from the famous Sunbaker (1937) series (bottom far right).

“I have to paint. It’s an obsessive-compulsive thing. And it is always beauty. I’m a slave to beauty. The beauty of the natural environment — it always has been, right from the very first.”

These days and under the management of Sri Lanka-born Vaj Ekanayake, his partner of 16 years and husband, Tim now exhibits and sells his paintings in their chic gallery, Tim Wilson Gallery, on Queenstown’s busy waterfront on Beach Street.

- French oak floors and kauri ceilings join Oamaru stone and copper as the main components of the build.

- It’s a place to enjoy an eclectic collection of objets d’art and art gathered over a lifetime.

- “I have a great love for the work of Frank Lloyd Wright and the Arts and Crafts movement, and wanted our home to reflect both of those loves along with natural materials,” says Tim.

- Vaj designed the garden. “I needed an empty canvas because I wanted to make a beautiful garden for Tim,” he says.

- “The flowers are the ones he loves, and I am proud of myself for learning how to create a garden and how to look after it. I chose amethyst as the primary colour as that is one of his favourite colours.”

It is a life devoid of “woulda, shoulda, coulda”.

“I am content. I am happy. And none of this would have happened without Vaj. He is the creator of it all. I am just not interested in the business side of things. He makes it work; he runs it and gives me complete freedom to paint, which is an utter luxury.

Vaj is a keen cook and loves to experiment using old family recipes for inspiration. His curries, made in the Sri Lankan tradition using tomatoes as the flavour base, are a family favourite.

“I do not have to answer to anyone. I’m doing exactly what I want to do. And I have a voice. I celebrate beauty at every opportunity, and I can bring it to people. And that’s the joy of it all.”

TIM ON HIS ART

“A good picture is about light, be it landscape, seascape, portrait, whatever; warm and cold, light and dark, side by side, and how these combinations affect us emotionally. It is essential when making a painting that the darks are well established in the initial process to ensure good contrast and enable a play of light.

“I am fascinated by colour and the fall of light on a surface and how it makes me feel. How do various colour combinations make me feel? Do other people feel the same way? Why do some people like green rather than blue? Oil paint is alive, and it teaches me something every day.”

“I use a lot of translucent, transparent and interference pigments and when the light levels change, the underpainting punches through with an incredible impact that creates an emotional response in the viewer.

“The technique, developed over many years, is unique. I focus on enabling the viewer to add detail in their own minds, creating their own story in the picture.”

TIM ON COLOUR

Tim acquires a lot of his pigment from the famous British paint maker Michael Harding, who produces colours especially for him.

“I pick up a tube of paint, take the lid off and — yippee — for me, that’s an unputdownable novel. The excitement continues to grow, and it is constant.”

Tim is most rapturous when describing a particular blue pigment.

Summer Rains Doubtful Sound.

“Michael Harding’s natural ultramarine is simply the best in the world. It’s made from gem-quality lapis lazuli found in one mine in Afghanistan. This is exactly the same pigment as the Old Masters used, then as expensive as gold, now not far off it. Rub it on your finger, and you can feel the texture of the stone. Spread it across the finger and see the extraordinary interplay of light created by the pigment and its effect on your skin and the blood beneath.”

Each painting takes six to 18 months, with 12 to 15 paintings completed in a year — working on several contemporaneously.

“I go into the landscape all the time — every day I will go and look. I am an observer. My work is not to everyone’s taste. However, the wonderful thing is that it makes some people happy and that makes me happy.”

This story was originally published in the May/June 2019 issue of NZ Life & Leisure

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.