Patrick Rattray’s Marlborough garden of surprises

- Patrick, at right with friend Ginny King, wanted his hedges, which form the symmetrical bones of the garden, to be yew. Yew does not like wet feet so they’ve been inter-planted with the more tolerant lonicera.

- Other hedges are a mix of hornbeam (“much hardier than beech”) and some are very closely planted leyland cyprus.

- The sitting room of Patrick’s house, which is identical to some of the most famous of Restoration period houses, opens to the vista of the Long Walk, seen across the rose garden and the rill to the Lutyens bench at the far end.

- In the past 20-plus years Patrick has planted every tree and bush on his heavy clay-based land, which is dry in summer, wet in winter and has cold south-easterly winds.

- He worked initially with his childhood friend and landscaper Jane Taylor (who subsequently died) on a planting plan that has stood up well in the two decades of planting since.

- The painting, by John Gibb, above the herringbone brick work of the fireplace in the sitting room is called The Oyster Fleet Leaving Bluff Harbour, 1889.

- The house’s double-height front entrance, with a formal arrangement of four rooms each opening off the fire-warmed entrance, is typical of the Restoration period, as is the upper-storey gallery.

- He wishes his dining table could talk as it came from his childhood home at Ngahere, near Waimate, and given his ancestors’ ironic Irish wit, he thinks it could tell a tale or two.

- The Rayburn wood stove which burns 24/7 during the winter is the heart and hearth of the home and heats the house

- Very tall chimneys are a trademark of Lutyens architectural style and Patrick’s, 15-metres from ground to chimney top, are best appreciated from the far-end of the Long Walk. Sir Michael Fowler, who designed the house, christened the western aspect of the house the Gin and Tonic Porch – the name has stuck.

- The pinot noir grapes are grown for Jackson Estate and go into their award-winning Vintage Widow, one of the few (if not the only) pinot to have been in the Cuisine Top 10 for the past five years.

Planting in this geometrically composed garden was underway long before the decision was made to build a Restoration-period house in its centre. The two are a seamless match.

Writer: Kate Coughlan Photos: Paul McCredie

This article was first published in the September/October 2016 issue of NZ Life & Leisure.

Marlborough farmer Patrick Rattray planned a garden for a new house he thought he’d never afford. But he designed the gardens and grounds anyway, and he got to work planting.

He knew exactly where on his farm a new house would go – the same site as the original 1880s homestead that had burned down in the 1950s. One day he took visitors on walk around the area and explained the garden, as he saw it in his mind. The formal beds, a rill, the yew hedges… he could see it all. However, from the confusion on the faces of his guests he gathered that they were not seeing much beyond the thigh-high cocksfoot they were battling through.

At that stage, more than two decades ago, Patrick began spraying out patches in the grass and planting the trees he knew would one day – should the house ever be built – give the grounds the very formal structure he wanted. “I thought if I can ever build a house, this is the garden I want so why the hell not plant it anyway? When I explained I was planting a garden round a non-existent house people looked at me as though I came from the dark side of the moon. I suppose it was just an overgrown paddock, after all.”

And lo! behold what the miracle of water and healthy pinot noir vines have made possible – a most impressive Restoration-period house surrounded by a very large, formal garden. Lucky visitors to this year’s Nelmac Garden Marlborough can, for the first time, enjoy Patrick’s vision. He’s always lived very privately – though delightedly sharing the property with his extended family for holidays, especially at Christmas when all five bedrooms are full and the very large house teems with guests.

He says the Garden Marlborough event brings such great value to the province; it is time to do his bit and open his garden as part of it. Preparing the grounds to look their best for the early November event coincided with Patrick’s long-planned walk through northern Spain following the medieval pilgrimage known as the Camino de Santiago. So guests will be taking Patrick’s garden rather as it comes and that is likely to be just fine.

It is, after all, a garden of trees, formal structures, lawns, hedges, avenues and walks. He’s always been a great tree man. “If there’s one thing you can do to be remembered by, it is to plant trees,” he says. “I graduated from being an enthusiastic tree planter to a fanatical tree planter and, once you become a fanatic, you have to have one of everything. Every species of tree. Silly really as some of them just don’t do well.”

He didn’t go in for much of the frilly garden stuff, this Lincoln University-graduate farmer who comes from a long line of Rattrays connected to the land and agricultural businesses. His father farmed Ngahere, near Waimate in South Canterbury, but warned Patrick against taking over that property as it was cold, sour country (now planted in pines which he says is probably a good use for it). His grandfather, a professional soldier in the British Army (though a New Zealander by birth) came home and purchased Ngahere in 1922. His great-great-grandfather was the Rattray part of Dalgety, Rattray & Co, wool and grain merchants of Dunedin.

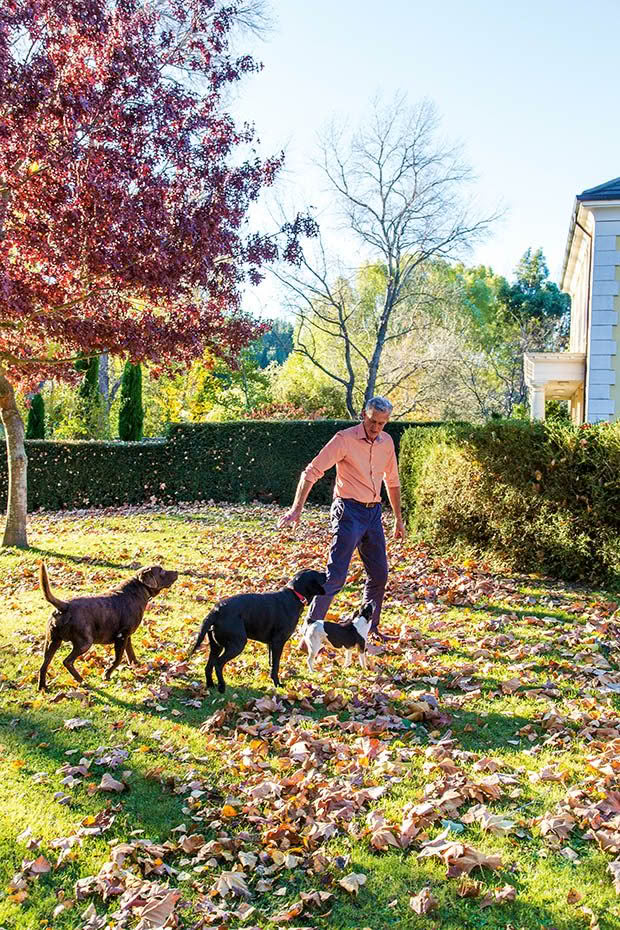

Constant planter Patrick Rattray, and his dogs Bruno, the brown lab and Whoppit, the terrier are joined by visitor Mack Oswald a black lab.

In the 1970s, after graduation, Patrick bought 200 hectares of Marlborough valley and found it hard to survive the dry summers. “The land looked a bit like central Spain, brown paddocks and a few scruffy old ewes. It was pretty tight trying to survive in the early days – uneconomic to run sheep and tough to grow grain profitably.”

Then two astonishing things happened. First, the grapes. They’d arrived in Marlborough in 1973 with Montana’s purchase of land for sauvignon blanc vineyards. Originally, the sought-after land was closer to Blenheim but the march of the grapes continued, inexorably, and eventually reaching far enough inland to border Patrick’s land.

Second, the water. In the mid-90s Patrick and some neighbours invested in an irrigation scheme. “Water came and changed everything. I could successfully irrigate with drip-lines for vines. Water was a 360-degree turn; if you have water you have life.”

And from the within the 100-square-metre farm cottage he then inhabited, he was then able to begin to think about building a new house in the middle of the already well-planted grounds.

Patrick had been influenced as a young man by his great-uncle Heathcote Helmore (the renown Christchurch architect whose city and rural homes from the 1920s and 1930s are, even today, among the province’s grandest). He says he’s always had an instinct for architecture and can look at a drawing and see what it will look like when it is built. He asked Wellington architect Sir Michael Fowler to design his house and was delighted by the response.

“I’d only met him once or twice and when I marched into his office and said, ‘Michael you have to build me a house’, he said ‘Yes, and we’re going to have fun’. And we did. It was really a delightful experience and such a learning process for me. I was still living in the cottage so I’d go across and talk to the builders every afternoon about what they were doing.”

“The house design, inspired by Sir Michael’s recommendation, is based on Restoration architecture of the late 17th century, prior to the Georgian period. This is the time when verticality was everything: houses were tall and symmetrical with an emphasis on their central entrance.”

Interestingly, Michael Fowler had worked briefly for Patrick’s great-uncle Heathcote Helmore, who’d in turn worked in 1913 in the London studio of Edwin Lutyens, the famous Edwardian architect who (among the many architectural styles he embraced and turned into Edwardian country houses) greatly admired the Restoration architecture of one of its greatest exponents, Sir Christopher Wren.

The house was built in 2001, hence MMI carved into the lintel above the the sitting room entrance.

The tilt-slab construction house was built in 2001, taking 10 months and 20 tonnes of concrete per slab. He found the process very exciting and dynamic, and on “pour days” he marvelled at the drama of it all – and heard the worst language of his life from builders worried the concrete would harden too quickly, which is saying something for a farmer. More important, he was so impressed with the quality of the interior concrete finish he has never plastered it – just added the skirting and scotia and painted it.

The resulting house is just as he wished it to be: easily holding its own among the formal grounds according to the Restoration principles of symmetry, verticality and order. It is also perfectly fitting for his lifestyle. “It is not a family home but it is a very good house to entertain in and, as many people are very good to me, I entertain them often. And it is very good for that.” And the grounds too are just as he wished them to be, with each separate area tempting visitors to want to know what is in the next garden area.

“My ideal was to create an element of surprise: you don’t see all the garden from one point, but there is always a gap leading you into the next area, drawing you through into another part of the garden. You are curious.”

Just as the visitor is intrigued to see what’s in the next area of the garden, so is inveterate tree planter Patrick keen to see which tree species he can get to grow next – although he admits to nearly running out of room for more trees.

WHAT IS RESTORATION ARCHITECTURE?

Building of this era (at the time of the restoration of a British monarchy – Charles II – after the death of Oliver Cromwell) is characterized by the use of classical elements such as symmetry. Charles and his court had lived in exile in Europe and their tastes were heavily influenced by the relatively simple, yet refined, style of Dutch architecture.

Manor, or country, houses were perfectly symmetrical, two storeys high with an attic roof. Famous Restoration architects include Inigo Jones, Sir Christopher Wren, Sir John Vanbrugh, Nicholas Hawksmoor and Sir Roger Pratt. The most famous Restoration building? Wren’s St Paul’s Cathedral, London.

See Patrick’s garden as part of Nelmac Garden Marlborough 3–6 November 2016. Tickets at: gardenmarlborough.co.nz

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.