Orchid growers put down roots in Titirangi tree house

Janice at the nerve centre of the orchid business. It would be nice to spend all day among the orchids but paperwork can’t be ignored.

Ice cream and photography were the unlikely stepping stones that led a couple to a house among the trees and into the exotic-flower business.

Words: Jane Warwick Photos: Duncan Innes Production: Janice Kumar-Ward

First published in issue #51 September/October 2013 NZ Life & Leisure

Janice Aagaard’s father had become so estranged from his Danish roots that the only word he knew in that language was kartoffel: potato.

That could well have been a portent because in a way it was the potato that was instrumental in how Janice’s life has turned out. That, and orchids.

Orchids were once the fancy of the rich. They were considered by some to be ugly, their frilly lips grotesque, while others saw them as an exquisite kiss. But, either way, they were made desirable by their exclusiveness as, outside their natural environments in such remote places as the slopes of South American mountains and Asian jungles, they were hard to propagate, despite having pods holding up to 500,000 seeds.

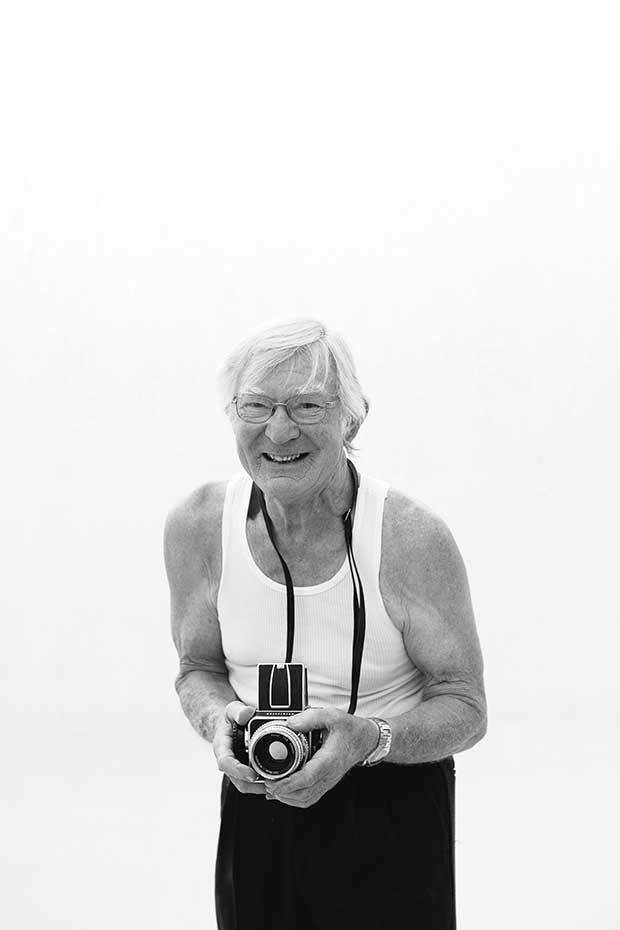

Helmut and his beloved Hasselblad camera which opened doors to all sorts of opportunities.

That something so apparently fecund should be so unproductive was a wonder to Professor Lewis Knudson, Emeritus Professor of Botany at Cornell University. He ascertained that orchids had no inherent food supply so he used them in his experiments to pinpoint which nutrients were necessary for the growth of green plants.

He developed a technique where seeds were artificially germinated and the new plants grown in sterile, closed flasks. He revolutionized orchid breeding by discovering a simple and almost foolproof way of producing new hybrids in large numbers.

One of the main nutrients in this ground-breaking development was a dextrose broth, often made from potato (or kartoffel as Papa Aagaard would have said).

This was, of course, before Janice was even born but it was just one of the curious connections that can be found in most people’s stories. The orchids were waiting in the future but in the meantime there were more fortuitous events.

The Larsen’s three-level house looks very Scandinavian which is no great surprise because they designed it themselves. When it was first built its many decks looked out over the tree canopy but now the trunks soar past.

Janice’s parents owned the Snowflake ice cream factory in Papatoetoe in Auckland and there came a time when they needed a new ice cream machine. Although the Aagaards had lost close contact with Denmark, they were fiercely proud of their Danish ancestry and when Mr Aagaard found there was an ice cream machine he could source from Denmark, he did so.

The owner of the machine’s manufacturing plant picked up on the Danish name – small wonder – and discovered the broken link with Denmark, did some research and came up with some cousins for Janice and her family to reconnect with.

While the Aagaards were rediscovering their Danish roots, a young man in Denmark was on track to put down some Kiwi roots, even if he didn’t yet know it. Helmer Larsen’s father was a photographer and, in time, Helmer became his apprentice.

By the time Helmer had earned his photography qualification, colour film had made an appearance and he was eager to try it.

His father, who hand-coloured black and white prints, thought this new development was nothing but a fad and that Helmer’s interest in it was wasted so Helmer decided to set out on his own. He bought books on the subject and taught himself the art of colour development.

All her own work: Janice’s beautiful orchids come in all colours. These are some of the varieties they sell to the New Zealand market.

He also thought he might emigrate to Canada but, although Protestant Helmer’s ideas and interests were catholic his devotion wasn’t, and at the time Canada was taking only immigrants of the Catholic faith.

Helmer had another idea. His father’s first apprentice, Edmund, had always kept in touch with the Larsens even after he emigrated to New Zealand. Edmund wrote, from the little cottage he rented on the property of a man who owned an ice cream factory in Papatoetoe, about his success and happiness in his adopted country.

It is hard for Janice to pick a favourite. Indeed, there are times when each new bloom becomes her new favourite.

Eventually he left the cottage and set up a laboratory processing black and white film on Dominion Road in Auckland City. Helmer wrote back: was there a future for another young Dane armed with a camera in New Zealand? And, if so, were New Zealanders interested in colour photography?

New Zealanders were interested in colour photography, it turned out. There was very little colour being developed here and most people had to wait for their films to travel to Melbourne and back. So come, come, encouraged Helmer’s new patron and bring as many books about colour photography as you can carry.

The stairwell that runs through the internal core of the tree house has a distinct Scandinavian feel.

Helmer came. He walked into the laboratory and there was the daughter of the man who owned the ice cream factory: the man who also owned the cottage Edmund had rented when he first arrived in New Zealand.

Janice Aagaard, studying languages at Auckland University, had a holiday job with the photographer. Soon it wasn’t only colour prints that were developing along Dominion Road.

Mr and Mrs Larsen Junior bought a little house in Titirangi. Janice graduated and Helmer photographed.

Janice at her loom where she weaves small rugs; grandson Leo, whose musical ability is not to be underestimated, tinkers on the piano.

There were three years spent in Denmark and three babies: Erna and her little brothers Lars and Flemming. And then, quite unexpectedly, there were orchids.

It was a striking orchid from North India that caught Helmer’s eye in a friend’s garden one day and he was given a cutting to take home. Other friends were impressed with how the plant thrived and gave Helmer several types of their own to try in what seemed an especially hospitable Titirangi climate.

This room is in the highest part of the house and gives the impression of sitting right in the tree canopy.

They flourished and Helmer and Janice were inspired to become more deeply involved in the whole orchid scene.

Helmer originally grew orchids simply for relaxation but he came to love them so much he eventually swapped photography for them full time. Janice and Helmer moved their orchids away from the Titirangi hills and onto the gentler slopes of Oratia.

In greenhouses fans rumbled, sending hot air rolling across the orchids to make them believe they were still on the side of a Peruvian mountain, in a deep, dank jungle in the Far East or perhaps in the spicy heat of a maharajah’s garden.

An antique mirror greets visitors to the house and reflects the kauri hatstand of which Janice was originally less than enamoured but has grown to love.

Helmer set up a small tissue-culture laboratory where he produced orchid clones to satisfy the huge demand from a budding cut-flower industry.

It was long before email and a little bit before faxes but the wait between letters only added to the excitement. There were orders placed and phone auctions all over the globe. The beautiful white mini Music Box Dancer ‘Ballerina’ crossed the Pacific from Santa Barbara and more types arrived from France.

They came from Australia, Asia and South America. There were original plants to be bought and hybrids to be bred from them.

The house is filled with furniture that show Janice and Helmer’s passion for Scandinavian and antique pieces. One of Janice’s finds is a lockable oak chest.

“Hybridizing is so exciting – you have no idea. Sometimes you get exactly what you want – other times you are startled and not always in a good way,” says Janice.

It began to grow a bit beyond a hobby and so the Larsens moved into the cut-flower business, supplying markets in Japan and the US in particular.

The Japanese liked whole stems covered with flowers and Japanese brides were known to plan their weddings around the seasonal availability of orchids from New Zealand. The Americans preferred a single perfect bloom: a buttonhole beyond compare.

As the business grew so did the Larsen children, thriving like the orchids and, in the manner of orchids, evolving wonderfully as hybrids of their parents. The boys went off to university and returned with science degrees.

Leo relaxes on a Danish couch, reading by the light of a Danish lamp.

Lars’ degree in cell biology meant that he could take over the laboratory and develop his own business in micropropagation.

The market changed again and the Larsens began to cultivate potted plants as well as cut flowers, opening up a wider domestic market.

Today in the cut-flower greenhouses cat’s cradles of strings stretch from the ceiling to the plants. They hold the stems straight and true to produce faultless sprays of perfect flowers.

In another greenhouse, where potted orchids are grown for the domestic market, pansy orchids with rich, red-velvet petals and leaves patterned with a wash of teardrops peer upwards. In full flowering season it will be impossible to see the plants for the flowers.

Scandinavian chairs in the loftiest part of the house with a prize orchid displayed in a vintage bottle.

In the corner are more simply shaped blooms that look for all the world like stylized humming birds, bobbing gently on the end of long, long, grass-like stems. There are orchids that look as if they’re laughing, some that look alien, some that simply look grotesque. All, Helmer is adamant, are beautiful.

It is the beauty of orchids that makes it all worthwhile, says Janice. Every day, even on horrid days when the wind is keen and the rain is tumbling down, she is able to work amongst some of the most beautiful flowers in the world.

Winter, she says, can be depressing for many people but never, ever for them.

SAVING THE ORCHID SPECIES

Orchid seeds grow slowly in the wild. They need birds and insects for pollination and to fall near a mycorrhizal fungus that will provide carbohydrates such as glucose and sucrose that they need to germinate.

These fungi are rare and land development and natural disasters that change the environment are ruinous to them. When jungle and forest are felled and the birds move out, orchids also disappear.

During World War II English growers were told to pull out their orchids to make way for food crops. They did so and sent the uprooted plants to the US, Australia and New Zealand, so saving many European orchid breeding plants from extinction.

DANISH DESIGN

The Larsens’ other love is Danish furniture. On that first trip to Denmark as newlyweds they bought an oak table and matching rocking chair, starting a treasured collection which is added to on each subsequent journey.

They also have a fondness for colonial New Zealand furniture which began with Helmer’s purchase of a kauri hallstand. When they renovated their house a special nook was built especially to display it.

Helmer also bought an old dresser, a piece that Janice was initially less than charmed with but which she has grown to love and appreciate.

First published in issue #51 September/October 2013

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.