Odd reasons your chicken might be lame

If you have a limping chicken, you need to turn detective and work through the clues.

Words: Sue Clarke

There’s no one symptom in poultry that has more possible causes than lameness. Often it may seem a mystery.

The most common reasons for a bird to go lame are:

■ a sprain, strain or breakage

■ genetic predisposition

■ diseases, i.e. virus or bacteria

■ other infective agents, e.g. a mycoplasma

■ a deficiency in the diet

■ something toxic they might have eaten

Running through a short checklist will often eliminate some of the possible causes immediately.

1. How old is the bird?

When a chicken goes lame, a common first response is to think ‘Marek’s disease’, a devastating virus that can cause limping, then paralysis, and often ends in death.

This can generally be ruled out if the bird is younger than six weeks old or older than six months.

Marek’s is most commonly caught in the first 2-3 weeks of a chick’s life, but it has a long incubation period so symtoms won’t show until a bird is 10-24 weeks old.

If it is older than six months, it is unlikely to be Marek’s disease. There are some exceptions, but these are rare.

2. Examine the bird

The next step is to examine the bird in more detail.

Feel the legs right from the thigh, high up under the feathers, down to the hock joint (the drumstick), then down the scaly part to the toes and the sole of the foot. Gently flex the leg out (if you can without causing pain). Compare the legs, including their temperature.

■ is the amount of movement the same for both?

■ is there any ‘crunching’ noise of bone ends in a joint when you move the leg?

■ is there any swelling, eg is part of one leg hotter?

■ are the soles of the feet soft and clean with no scabs or black lumps?

■ are there mud balls adhering to the claws or the sole?

■ can the bird walk at all?

This will help you work out whether the bird has a physical injury to a tendon or joint, or an infection in its skin, most commonly on the underside of the foot called bumblefoot.

If a bird seems healthy but is suddenly unable to move, it could also be a spinal injury or a sore on its keel/breastbone.

3. Extra checks

A couple of symptoms are going to indicate a surprising cause:

■ does it also have a twisted neck, toes, or is completely paralysed?

■ when you bend the leg at the hock, do the toes curl (as if perching) or not?*

*they should curl in a healthy bird

If you see one or more of these symptoms, the cause is likely to be a nutritional issue. Confusingly, a shortage of essential vitamins and minerals can affect some birds and not others in the same flock eating the same diet.

Deficiencies in the diet of breeding birds can also result in their chicks being deformed. These deformities may not always be apparent in a newly-hatched chick, but may get worse as the bird grows. Curly toe paralysis is an example of this, caused by a shortage of B2 (riboflavin).

DO SOMETHING

If a bird is lame, unable to walk or paralysed, and you are not sure what is causing the issue, you need to do something to alleviate its distress. Poultry are prey birds; if they are showing obvious signs of pain or discomfort, you have a duty under the Animal Welfare Act to act, be it treatment, going toa vet or euthanasia.

POSSIBLE CAUSES OF LAMENESS/PARALYSIS OR INABILITY TO MOVE NORMALLY

This list may not give a complete fit for your bird’s symptoms, but if age and one external symptom match, you are much closer to working out the cause.

Hatching

Symptoms: Stargazing (staring upwards), backwards somersaults

Possible cause: Congenital, or vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency in breeder diet

0-20 weeks

Symptoms: Lameness, swollen joints, lesions

Possible cause: Erysipelas (a bacterial infection)

1-3 weeks

Symptoms: Jerky movement or tremor, lying on one side

Possible cause: Epidemic tremors (Avian encephalomyelitis),

a virus passed through the egg to the chick

1-8 weeks

Symptoms: Losing balance, outstretched legs, spams, twisting of the head

Possible cause: Encephalomalacia (affecting the nervous system), can be genetic or nutritional

(caused by lack of vitamin E)

Symptoms: Circling, unable to stand, head twisted back

Possible cause: Rickets (nutritional shortage calcium and vitamin D)

Symptoms: Legs twisted out to the side

Possible cause: Perosis, where a tendon slips off the joint (choline, calcium, vitamin D shortage)

Symptoms: Curled toes

Possible cause: Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) shortage

3-6 weeks

Symptoms: Squatting with feet up and weight on hocks

Possible cause: Spondylolisthesis (‘kinky back’ or pinched spinal cord), more common in fast-growing breeds

3-20 weeks

Symptoms: Lameness and lack of coordination

Possible cause: Necrotic dermatitis (bacterial disease)

4+ weeks

Symptoms: Degenerated leg muscles

Possible cause: White muscle disease (selenium deficiency, NZ grains are low in selenium)

4-8 weeks

Symptoms: Lameness

Possible cause: Viral arthritis

4-12 weeks

Symptoms: Lameness, swollen hocks, depression, stunted growth, shrunken comb

Possible cause: Infectious synovitis (bacterial infection)

10-24 weeks

Symptoms: Droopy wing(s) dragging leg or one stretched forward and one back

Possible cause: Marek’s disease

18+ weeks

Symptoms: Abscess on foot pad

Possible cause: ‘Bumblefoot’, bacterial infection of Staphylococcus aureus caused by injury (see page 74)

Symptoms: Lameness, thickened leg bones, stilted gait, roughened scales on legs

Possible cause: Scaly leg mite (check for disrupted scales), or Osteopetrosis (caused by a viral infection)

Symptoms: Limping, paralysis that spreads over the whole body, convulsions, swollen joints, lack of coordination

Possible cause: Botulism (common bacterial toxin found in rotting plants or animal carcases); Toxic algae; Toxic weeds, ie black nightshade, hemlock, sweet pea, karaka

IF IT’S A VIRUS

If you suspect Marek’s disease is the most likely cause – and it can affect up to 20% of young growing, unvaccinated birds – then time will tell whether it is the temporary or transient form, or whether it will eventually lead to death. There is no treatment available.

Epidemic tremors in young chicks has no treatment and paralysed chicks usually die from starvation, so you need to ensure humane euthanasia.

Viral arthritis in the hock and toe joints cause them to be hot, swollen and puffy. This can be helped with antibiotics from a vet to treat secondary bacterial invaders.

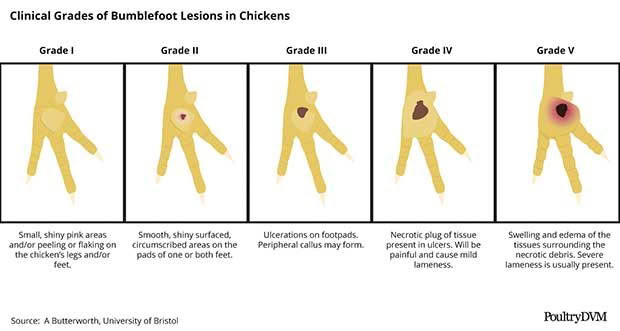

BUMBLEFOOT

This is a healthy foot, but mud sticking to the pad can cause bacterial infections.

This affects the pad of the foot. It will be swollen or have a large black scab, indicating bacteria (most likely Staphylococcus aureus) has invaded the skin, and it can then spread to the joints.

If the foot has been punctured, or the sole kept moist by balls of mud/faeces sticking to it and the claws, the bacteria can invade through the softened and/or damaged skin.

The swelling will have to be lanced, the hardened pus removed, and antibiotic spray or salve applied to the open wound until it heals. See a vet for assistance.

CLINICAL GRADES OF BUMBLEFOOT LESIONS IN CHICKENS

YOUR FIRST STEP IF A BIRD IS LAME

Segregate and confine it to a box or cage in a warm, but well-ventilated place and treat it if possible. Make sure it has access to clean food

and water.

If a limp is caused by an injury, segregation and confinement is important. It prevents other birds or predators getting access to and possibly attacking an immobile bird, and helps to stop the bird from putting pressure on its injured limb.

If the bird is sick, it helps to prevent spread of the disease.

PARASITES

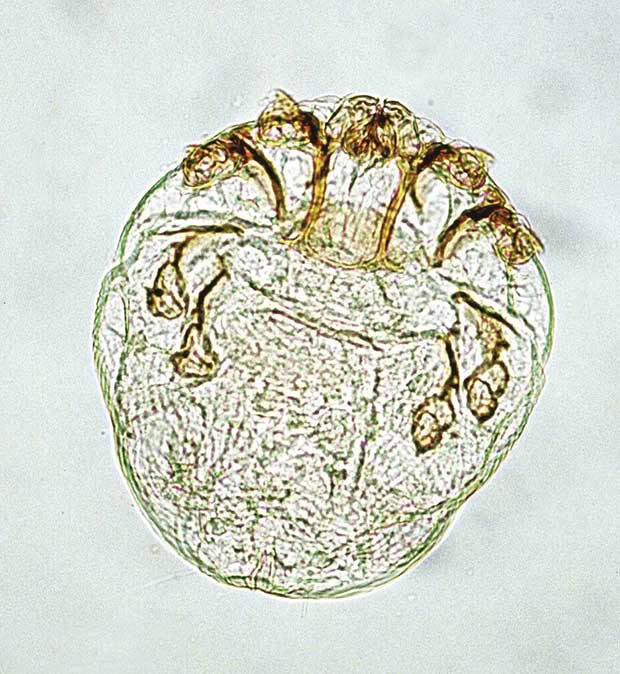

Scaly leg mites are the most likely parasites to cause limping and lameness in growing and adult poultry. They are very common, spreading easily within a flock, and when introduced by new birds which are infested.

The mite burrows beneath the scales of the legs and feeds on the skin and tissue. The scales will appear lifted and roughened, and bad cases may bleed, look deformed, and be covered in crusty material.

Knemidocoptes mite

To treat it, you need to kill the mite. Cover the legs in a thick barrier of grease, oil or petroleum jelly and apply it frequently (every 1-2 days) over 10-14 days. This suffocates the mites, and will also soften the damaged scales, which will eventually fall off and be replaced by new, shiny, smooth ones.

■ Light vegetable oil can be used but this needs to be applied more frequently than something with a thicker texture.

■ An old toothbrush is a good tool to thoroughly work a barrier into small gaps and around all the scales.

■ A general pest treatment like ivermectin applied at the same time can aid in eradicating the mites.

DO NOT

Do not use kerosene or diesel. This is an old-fashioned method which can burn the skin of the chicken, and both are toxic substances that can be absorbed into a bird’s system.

10 things every chicken owner should know about Marek’s disease

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.