NZ Lifestyle Block Smart Series Part Six: Lessons from Rhys Taylor’s award-winning 10-year-old eco home

This award-winning Geraldine home is 11 years old and still way ahead of the average NZ house.

Words: Nadene Hall Images: Kirsten Sheppard Additional images: Rhys Taylor

Who: Rhys Taylor & Anne Griffiths

Where: Geraldine, 140km south of Christchurch

What: masonry-concrete home with grid-tied solar energy

Land: 6ha (16 acres), 3ha protected native bush under QEII covenant

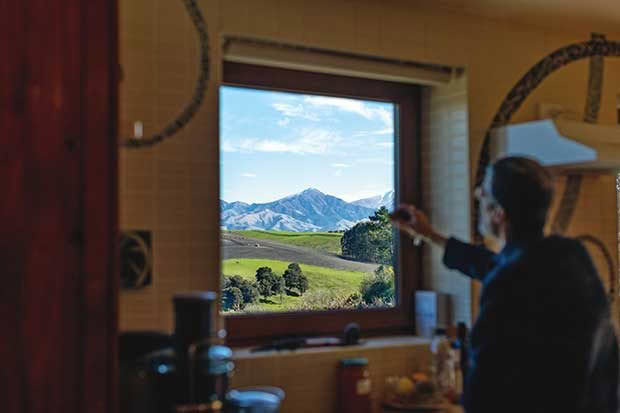

Rhys Taylor and Anne Griffith’s property has a picture-postcard view. Literally.

“It’s a very beautiful spot,” says Rhys. “And to our amusement, it appears on a Geraldine postcard.”

When they built their smart house back in 2008, they knew they’d have no need for art on the walls. Instead, carefully placed windows ensure the spectacular views of the majestic Four Peaks Range are framed to perfection for anyone working in the kitchen or sitting in the lounge.

They bought the land in 2003.

“But we couldn’t afford to do anything else, we certainly couldn’t afford to build a house,” says Rhys. “We used to come down here (from Christchurch), set up a tent and garden on weekends away.”

That gave them time to make observations about the land.

“A lot of thinking went on about the design of the site so the landscape was used to best advantage. It was helped enormously by us spending time here camping before we built our house. We planned out all those things rather than just launching straight into building.”

The house sits at the end of a long driveway, on a platform cut two metres deep into a west-facing, clay hillside.

“Fortunately, we didn’t hit rock, because there is volcanic rock further down,” says Rhys.

“We’re completely screened from our neighbours to the east and it also gives shelter from the prevailing wind in Canterbury.”

There is parking on the southern side of the house. The retaining wall that forms one side of the couple’s home extends around the garden, forming a sheltered courtyard.

THE HOUSE

Size: 1-bedroom, 90m²

Designer: Roger Buck

Builder: Henderson Building (2006) Ltd

Award: Gold – South Canterbury Registered Master Builders Association, 2008 House of the Year, Sustainable Home under $500,000 (for Henderson Building)

Wastewater: septic tank and reed bed

Water: 1 x 25,000, 1 x 8000 litre storage tanks for irrigation, rural water supply for drinking

THE DESIGN

Design principles: passive solar, high thermal mass house

Construction elements: concrete, concrete block, limited glazing

Christchurch architect Roger Buck was considered a leader in energy-efficient, sustainable builds, most using large amounts of concrete to create thermal mass. He was renowned for creating homes that were pleasant to live in.

“We went to visit some houses of his clients and we found that the interior environment was wonderful,” says Rhys. “They obviously had very stable temperatures and we saw some of them on very hot days and they were cool inside.

“The owners of those houses praised the experience of living in them. For example, no condensation, no cold spots.

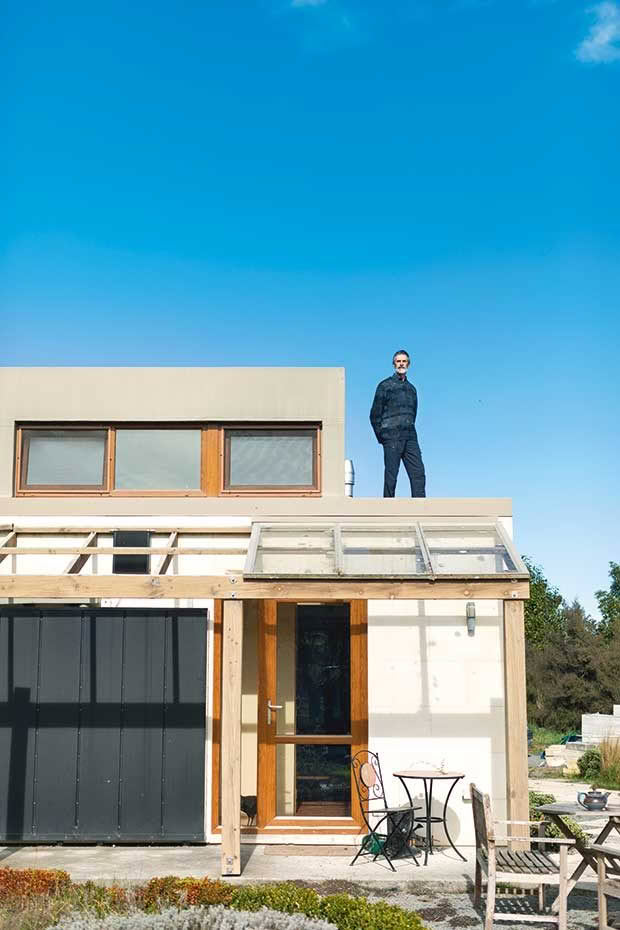

The view from the green roof, with a hint of the Four Peaks Range through the clouds.

“A lot of concrete is used in the construction of the house, so that any heat you get in, stays in. And in the summer, it’s also cool.”

The ex-pat UK couple has no children and no family who may need to live with them. That meant they could save a lot of money building a house just for themselves.

“We’ve got a small footprint, about 90m². Rather than going for a big footprint house and skimping on quality, we’ve gone for a small footprint house of high quality.”

Rhys says the long-term performance of the house was also an important aspect of the build.

“During the lifetime of this house, it will perform well in a warmer world. It will cope better with overheated summers. Knowing how the climate is changing… we’re going to have super-hot summers, and we really did need a house that would cope with that.”

The wood burner is the smallest clean-burning option you can buy and only needs to run for two hours a night during winter.

The bonus is that Roger Buck’s design is also seismically strong.

“The many concrete homes he designed came through the Christchurch earthquakes virtually unscathed,” says Rhys. “The massive concrete structure means the whole thing is locked together. In the event of an earthquake, the whole house moves as one unit.”

THE STRUCTURE

Floor: insulated concrete slab

Exterior cladding: Oamaru stone | Parkside Quarries

Walls: steel-reinforced Firth concrete blocks, filled with a Duracem cement-concrete mix

Insulation: extruded polystyrene panels

Even the concrete in this home is smarter than average. It contains a high proportion of fly ash, a by-product of steel-making.

“It works like cement but has a much lower carbon footprint because you’re using a waste product from steel-making,” says Rhys. “We got this low-embodied energy concrete… in place of some of the (conventional) cement.”

A concrete retaining wall holds back the hillside and forms the eastern wall of the house. The north-facing front of the house is mostly windows, with a solar air heater.

The exterior is Oamaru stone, with an air cavity behind it for ventilation, as it’s slightly permeable. Behind that is a layer of extruded polystyrene insulation.

“The sheet insulation fits tongue-and-groove without gaps, whereas in timber frame houses you have heat loss because of the stud work.”

THE INTERIOR

Kitchen: rimu and macrocarpa, natural oil sealer

The couple did not want to use MDF in their cabinetry, to avoid volatile gas emissions. Binders and resins in MDF can give off carcinogenic formaldehyde gas for years. They also didn’t use – to their knowledge, says Rhys – any polyurethane sealer. The floor is covered with terracotta tiles.

“We’ve got relatively little plywood, we don’t have any vinyl flooring or any artificial carpets either. So very little in the way of volatile gas emitters and the air quality of the houses is greatly assisted by that. It’s a very ‘clean’ house in that sense.”

Natural products were important to Anne and Rhys, to avoid volatile gas emissions. The house has terracotta tiles on the floor, and a kitchen made from rimu and macrocarpa.

THE WINDOWS

Joinery: unplasticised polyvinyl chloride (uPVC) in a faux oak finish

Glazing: double glazed, with lowE film and filled with argon gas | NK Windows

One of the picture windows, framing the Four Peaks Range.

The couple’s tilt-and-turn windows are of German design. Turn the handle horizontal and they open sideways, for easy cleaning. Turn the handle up and they tilt open from the top, for ventilation and security.

“The frames are uPVC so they are plastic but they’re ultraviolet resistant and they’re formed to look like oak – everyone thinks it’s wood.”

uPVC has the highest insulation value of any window framing you can use, with very little heat loss and no condensation.

An important design factor is the lack of windows in the house, to help maintain warmth in winter, and keep it cool in summer.

“Very big footprint houses have loads of picture windows and they’re completely thermally inefficient,” says Rhys. “They overheat (the house) in summer and are too cold in winter.

“Very few of our windows are large. We don’t have big picture windows, we’ve got windows that work like pictures – quite a few are square. I’m looking at the Four Peaks from here, and it’s perfectly framed by the window.”

The solar airbox sits on the north-facing wall of the house, generating hot air that is 20°C warmer than outside. It is blown into the coldest part of the house by a fan, warming it, and also helping with ventilation. The fan is turned off in summer.

THE HEATING & VENTILATION SETTINGS

Heating: Metro Tiny Rad wood burning stove | Metro Fires

Underfloor heating: Thermofloor

Ventilation: passive solar ‘stacking’

Rhys says thanks to their home’s high thermal mass, which absorbs large amounts of heat during the day, they only need a small wood-burning stove to heat their home.

“It was the smallest clean-burning woodstove we could buy and that is sufficient heating if we burn it for two hours a day (in winter) – that’s all it needs. We grow our own wood which we use for fuel, so we’re carbon neutral, we’re only burning wood that grows on our site.”

Another important heating system started as an experiment. At the front of the house is a large, black, square, flat box fitted to the wall. It has very small, regular-sized holes in it, and a vent at the top. In winter, a small, 12-volt, solar-powered fan pulls hot air out of the black box and blows it into the coldest part of the house.

“The airbox, being black, heats up whenever it’s sunny. When you have enough sun to power the solar panel, which powers the fan, you also have enough heat to warm the air. The fan starts up automatically and draws air into the box from outside.”

Rhys says the system is very effective.

“It raises the temperature of the air in winter by 20°C. If it’s a 10°C day outside, and we’ve got sunshine, the air coming into the house, which is a small volume of air, comes in at 30°C.”

This air helps to warm and ventilate the house. Any moisture, from bathroom steam or cooking, is picked up by the warm air and ventilated out the pop-up clerestory window on the roof (pictured beside Rhys above, and from inside, below).

This type of window has been used by architects since ancient Egyptian times to allow more light into a building. However, on the sunny side of an energy-efficient house, they can also play a big part in ventilating air, passively heating or cooling a house. It’s known as a solar stack.

“The clerestory windows face north and let beautiful light into the house,” says Rhys. “But more interesting, in winter, on a sunny day, we have those windows open all the time.

The clerestory window in the bathroom helps to ventilate moisture out of the house.

“The warm humid air rises and goes out of the clerestory windows, which removes condensation. We don’t need an extractor fan in the bathroom because the natural stack ventilation of having a north-facing window open at the highest point, plus warmth in the concrete walls, drives a gentle airflow that takes out moisture automatically.”

Years of living in cold rental properties and his experience in sustainable building have shown Rhys that New Zealanders don’t fully understand the concept of heating and ventilation. Warm air carries a lot of moisture.

“If your house is warm and you have lots of steam from cooking or from baths and showers, unless you ventilate it pronto, it’s going to condense somewhere else in the house, like the back of your wardrobe.”

THE LIVING ROOF

Concept: habitat for native skinks

Original plants: 30 native species

Current plants: mostly exotic grasses

Most people don’t think of their neighbours when they build a house, but Anne and Rhys wanted to preserve the unspoiled views of the stunning mountain range for the people living next door.

“We deliberately planned it so our neighbours see only the view of the four peaks – they don’t see our house.”

The roof is level with the hillside, meaning it’s easy for Rhys to access it.

A concrete block retaining wall on the east side is also the exterior wall of the house, providing an almost seamless transition from the hillside to the roof. The roof is made of concrete panels, covered with a layer of poured concrete.

There are layers of insulation, a butynol waterproof membrane, geotextile mats as root barriers, a layer of shingle, and a thin layer of soil (about a hand-span deep). Drains between the hill and the roof channel stormwater into a storage tank.

The couple weeded the roof religiously for the first 18 months to preserve their plantings. Today, Rhys uses the mower.

“We probably had too much soil depth, and it was too fertile for low-growing natives to compete with the exotic pasture grass seeds that blew in, and soon shaded them. Many do persist as an understory to the grasses. There are skinks there!”

Their roof ‘meadow is mowed once a year.

The original plantings were a mix of native grasses and groundcovers.

“We’ve got sufficient soil depth that it doesn’t dry out, so it stays green. East of the house, at the same level, is a food garden, separated from the roof, for visitors’ safety, by a corokia hedge.”

“Corokia was chosen as it is a clippable hedge and the fruits are useful lizard food.”

ENERGY

Panels: 9 Mitsubishi photovoltaic (PV) panels with Enphase microinverters

Total energy generation since installation in October 2016: 6.9 MWh (Mega-watt-hours), exported at 9c/kWh

Solar hot water: Thermocell solar hot water system | Atone Engineering

Installation: Auric Electrical

Even the underfloor heating in the bathroom is powered by solar. It’s on a timer, meaning Anne and Rhys wake up to a warm floor.

In the morning, the solar panels power appliances like the washing machine and dishwasher. In the afternoon, it helps to heat the couple’s hot water supply and recharge Rhys’s laptop.

The house is still on the grid because the couple doesn’t have batteries. They buy in power when it’s dark, but all the efficiencies in their home mean even in the middle of a cold, dark winter, their worst power bill was just $113.

“The next logical step would be to add batteries,” says Rhys. “(Our system) has been designed to include extra panels. We’d probably then add batteries and would be even more efficient because we could generate a surplus during the day and store it for use at night.”

Their array of nine solar PV panels all face north but are at different angles: 25 degrees off horizontal on the veranda (summer-optimised); 45 degrees (winter-optimised) on the two woodsheds. The wood sheds doubling as frames for the solar panels had great appeal to Rhys.

The solar system includes panels (on the porch pergola) that power the house during the day. Solar thermal panels sit above the hot water cylinder and preheat the water to 40-50°C.

“We’re quite interested in permaculture and one of the principles I’ve always liked was that everything should have more than one function to be more effective.”

A solar water heating system pre-heats their water to 40°C, sometimes up to 50°C – “if we’re lucky”. A sealed, glycol-filled pipe is heated by a series of panels on the roof. It runs down into the hot water cylinder, transferring heat, then back to the panels. The hot water cylinder’s top section is heated up to 60°C each afternoon by power from the PV panels, controlled by a timer.

“I wouldn’t say our hot water is free, because we had to buy all the equipment, but using that equipment, we get a reliable supply of hot water every day.”

Anne and Rhys are planning an extension to their house. Adding extra solar panels and micro inverters to its roof would turn them into power exporters.

“If we install a minimum of 2.4 kWh capacity of batteries when building phase two, we could cover some morning and evening peak demands (like the electric jug, cooker, lighting), or lower our overnight power use (freezer, fridge which run 24 hours a day) from a stored daytime surplus.”

Would solar work on your block?

To get the best from solar panels, it’s important to orientate panels to solar north and at a slope angle close to your latitude. The free-to-use Solarview calculator from NIWA helps you to work that out, using your location. It shows the differences between summer and winter potential generation in kWh/sq metre per day.

The cool-store larder

Size: 2m² x 2.5m²

Average temperature: 6°C lower than the living space in the house

The cool temperature larder is on the colder, southern side of the house

Anne and Rhys are enthusiastic preservers, storing fresh, long-keeping fruits, and bottled fruit, juices, jams, chutneys, and root vegetables. They also use the larder to store bulk groceries and the occasional wine or beer bottle.

“We’ve got an exterior grade insulated wall that separates the living space from this part of the house in the south-east, which was always going to be the coldest bit,” says Rhys. “We needed a wall strong enough to hold the roof up (anyway), but also decided we needed a fully insulated wall.”

The temperature in the larder is, on average, 6°C colder than in the main part of the house, providing good conditions for food storage.

3 things Rhys would do differently

1. Build a second bedroom

A house with a small footprint is important, but over the years, Rhys and Anne have had an increasing number of visitors. They are now building a small extension to house a guest bedroom, an office, and a food processing area so they can preserve large amounts of food without having to cram it all into their home kitchen.

2 No big picture window

An important rule of passive solar homes is to keep windows to a minimum, with most glazing on the northern side. When Anne and Rhys built the house, they included a triple bi-fold window on the south-west side to take in the views.

“It overheated us in the summer,” says Rhys. “We took out that window and extended our lounge out by 2m which gave us space for the woodstove.

“On summer afternoons, when the sun is low but still very powerful, we just took in more heat because having a structure like this, all the heat that shines in gets soaked up… and we overheated in summer. We installed small windows instead and now it works very well.

“It may have been a design fault early on, but the end result is really good.”

3. The green roof

The couple are very proud of their roof, but Rhys says it was a big expense.

“I would think twice about doing such a massive green roof and retaining wall structure because it added many thousands to our construction costs… I probably would have tried to afford to have a two-bedroom house rather than a one-bedroom one from the start.”

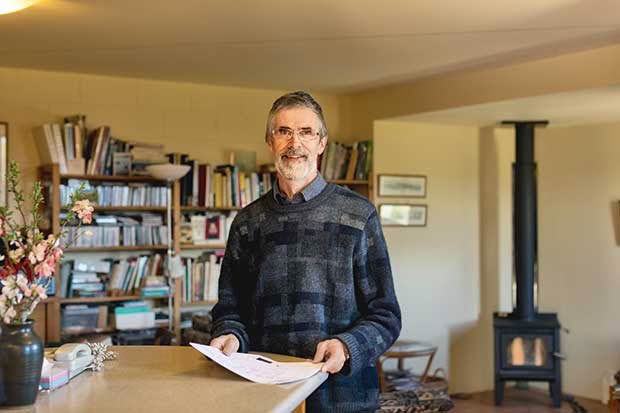

Rhys Taylor

National Co-ordinator, Sustainable Living Education Trust

Rhys is the national coordinator of the Sustainable Living Education Trust which runs the Future Living Skills community education programme.

Its courses cover aspects of sustainability, including eco-building, energy efficiency, water use and river protection, growing organic vegetables, waste minimisation, healthy food choices, travel options, and carbon impacts, and community resilience.

The courses are available online for free, by registering at sustainableliving.org.nz

MORE HERE:

How New Zealanders can build smarter and more efficient homes