Why Mt Eliza raw milk cheese has the critics tweeting

Jill Whalley.

Katikati couple’s artisan efforts are proving to be the big cheese.

Words: Anna Tait-Jamieson Photos: Simon Young

The cheese room is warm, damp and smelling sweetly of milk on this crisp morning in autumn. It’s cheddar-making day at Mt Eliza Cheese and Chris and Jill Whalley are bent over the vat, lifting, stacking, turning and re-stacking wet slabs of massed curd.

The process, called “cheddaring”, has been in use since the mid 19th century and, while it looks pointlessly repetitive, there is method in it. As the lumpy curds bond together under their weight, the slabs become smooth, elastic and shiny.

From cow to cheesethe artisan process is entirely hands on. Chris and Jill Whalley stack and mill the curds then press them into wheels that are routinely turned and core-sampled to ensure they ripen correctly.

“Cheddaring changes the whole structure,” says Jill, as she tears off a piece of the curd. The texture is like cooked chicken breast; it tastes fairly bland and it squeaks between your teeth like halloumi.

“The idea is to get rid of the whey,” adds Chris. “As the whey drains, the acidity develops – we test for acidity along the way – and one of the ways we control the microbiology is by controlling the acids.”

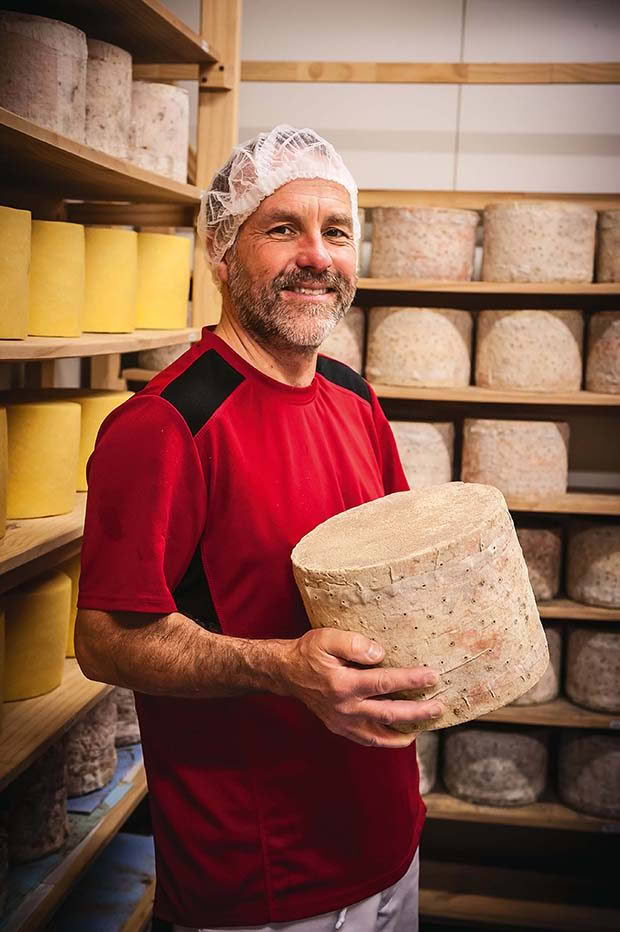

The science comes easily to Chris. An industrial chemist by trade and an artisan by nature, he’s found his niche in a craft that melds technology and tradition in equal measure.

Chris Whalley.

The decision to change careers came about when the couple decided to leave Chris’ homeland in the UK and relocate to Jill’s home patch in the Bay of Plenty. They had no idea what they would do to support their proposed new lifestyle until one day they happened to visit a cheesemaker in Wales.

“We sat in his garden drinking coffee and there was this moment when the light bulbs came on,” recalls Jill. “We looked at each other and said, ‘We could do this.’”

It all happened quite quickly. Chris trained with specialist cheesemakers in Wensleydale. In 2007 they settled their family on a lifestyle block near Katikati and built a small dairy factory on site. From the start they specialized in British farmhouse cheeses: notably cheshire, cheddar, red leicester, double gloucester and a stilton-style blue.

Chris’ first cheeses were well received and he could have rested on his reputation at that point but he’s a perfectionist. So when the government relaxed the rules to enable cheesemakers to use unpasteurized milk, he jumped at the chance.

He and Jill have been sorely tested by officialdom but in March 2015, more than four years after their initial application, they won approval to launch their first unpasteurized cheese – a fine-tasting, cloth-bound red leicester.

They’ve since added a cheddar and a blue to the unpasteurized range. Chris explains it in scientific terms: “Raw milk retains all the micro flora that adds to the character and flavour of the cheese. And, we’re not killing enzymes or denaturing the proteins unnecessarily so it helps with texture and flavour.”

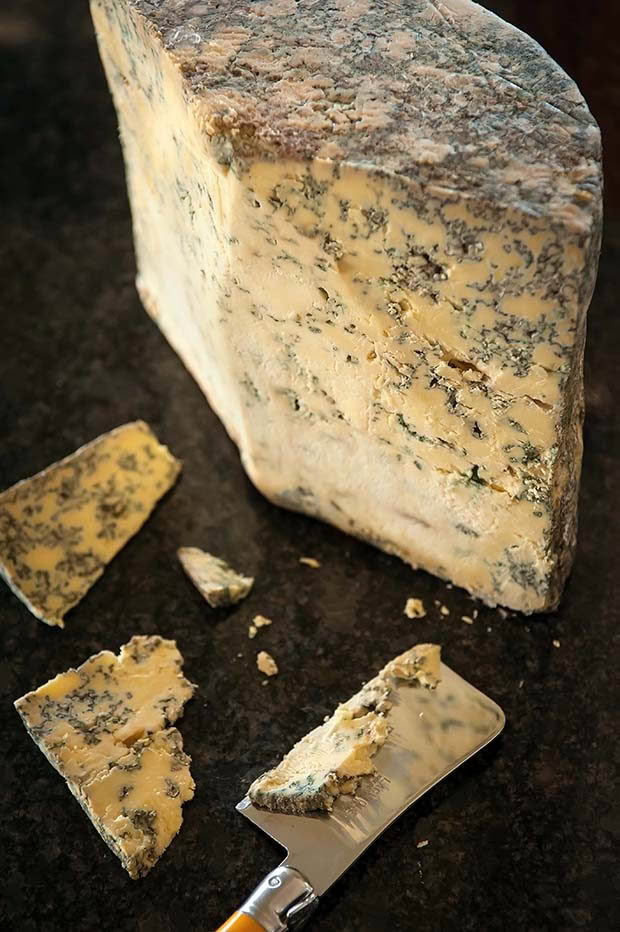

Mt Eliza red leicester and blue cheeses are cloth-bound in the traditional farmhouse way, the others have the sort of edible rind you’d find on a gouda. The seven-kilogram wheels are aged from four to 12 months and are sold to specialist cheese shops, at farmer’s markets and by mail order. The lengthy maturation process of hard-pressed raw-milk cheeses helps kill off any bad bacteria. “It’s one of the control measures we have to make sure pathogens won’t survive,” says Chris.

Cheesemonger Calum Hodgson of Sabato is more effusive. On receiving his first sample, he set Twitter a flutter with a tweet that compared tasting Mt Eliza’s raw-milk cheese to watching colour television after years of black and white. Since that tweet took flight, production has trebled.

The feedback and the subsequent awards they’ve received have given the couple a much-needed boost after the marathon effort of getting their raw-milk cheeses over the line. The Ministry for Primary Industry (MPI) has set rigorous guidelines for raw-milk cheesemakers.

They must have stringent risk-management programmes for both the farm milk and dairy operations, as well as “validation protocols” for each type of cheese. Only Mt Eliza and Aroha Goat Cheese have achieved this so far.

It’s been a steep learning curve for Chris and especially Jill, who works as an occupational therapist when she’s not helping in the cheese room. “This is my bed-time reading,” she says lifting up a hefty textbook, Microbes in Cheese. She has made it her mission to understand the science behind all the tests.

She keeps a spreadsheet with a line for each batch of cheese and records the measurements at every step of the process, from the cowshed to the ripening room. Temperature and acidity are recorded on site and a further 17 samples are sent to an accredited laboratory, where they’re tested for pathogens.

“It’s been tough,” agrees Chris. “We have been breaking new ground in New Zealand – the regulations are tougher here than they are for imported raw-milk cheeses made in the EU. In many ways our raw-milk cheese is safer than pasteurized because we’re monitoring so much of the process.”

Which is not to say this is cheesemaking by numbers. “We use traditional English recipes so the type of culture, the temperature at which we scald the curds, the size of the curds, the salting, the manipulation, pressing, ageing and turning are all variables of the recipe. There are more variables with raw milk but that’s part of the beauty of it. You get variations in the cheese and we embrace them.”

After months of maturation in the ripening room, the flavours intensify. The cheddar is crumbly and tastes sharpish as a cheddar should, while the red leicester is more mellow and buttery with a delightfully nutty flavour that gets nuttier towards the rind. The Eliza Blue has completely sold out, with almost the entire first batch bought by Calum at Sabato, who was won over by its restrained blue notes and “farmy nuances”.

Chris admits to a preference for cheddar himself, and as he nibbles on a shard he considers what it is he loves best about his new vocation. “It’s making something that has so much character. It goes from quite a bland product into something with a huge amount of flavour, character and variability. And things don’t always work out, so there’s a bit of magic about it.”

Dairy farmer Carl Williams with assistant Joshua Watson.

MILKING IT

Any cheesemaker will tell you the magic starts with the milk. The Whalleys source theirs locally from Carl Williams’ mixed herd of friesian and jersey cows. Carl remembers the day they came to ask him to supply them. “I thought, ‘Why not? It’s a good opportunity for Chris. So long as I don’t have to do any paperwork.’”

Well, that proviso came unstuck very early on. Not only does Carl have a lot more paperwork, but also the milk-testing standards are higher and he’s had to improve the cooling systems in his shed. Not that he’s complaining. He says it’s rewarding knowing a small portion of his milk is contributing to an award-winning product. He loves the Whalleys’ cheese, and their spirit. “I take my hat off to them with all the hoops they’ve had to jump through.”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.