Meet the family who kept their 1970 Datsun 240Z in California for three generations

This resilient little Datsun has provided a lifetime of special moments to three generations of the Davis family. Grant Davis calls it his ‘sunny-day’ vehicle.

Words: Jane Warwick Photos: Grant Davis

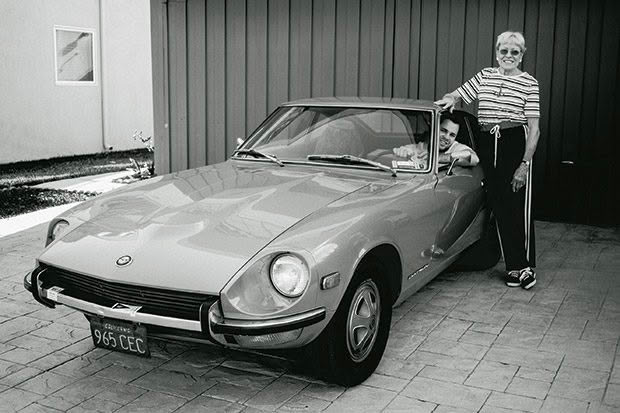

Nearly five decades, 10,000 kilometres, three sons, five grandchildren and an ocean after the Davis family’s 1970 Safari Gold Series 1 Datsun 240Z left the lot, Grant Davis’ grandma still couldn’t help but smile when one of her grandchildren took her for a spin.

It didn’t matter that the car was noisy and that insulation was non-existent. It didn’t matter that passengers could hear the diff whine, nor that they felt the change of every gear and every stone that flew up under the chassis. And it didn’t matter that no one was bothered by the wafts of exhaust caused by the leaking seals, or that the engine pumped out heat and the one-speaker AM radio crackled off station.

It wasn’t dark, so the headlights that made driving at night feel like being guided by candles weren’t needed. And it wasn’t raining so it didn’t matter that the wipers were pathetic. What mattered was that Grant had his treasured grandmother, Libby, sitting beside him and she didn’t just smile, she beamed from ear to ear. And that, says Grant, is something he will never forget.

There was a chance that jaunt might never have happened because after Grant’s grandad Whit passed away, Libby couldn’t bear the sight of the vehicle, the zippy little two-door sportscar her submariner husband, then based in San Diego, had bought for her.

There weren’t very many small cars in San Diego in the 1970s; Americans had a love affair with excessive horsepower and wide chassis, egged on by their other love affair with outer space. Cars started to emulate rockets, with big headlights and futuristic fins. America also had broad roads cutting through its wide-open spaces, so the more horsepower, the better to rip through the countryside.

The 240Z was just the thing for Whit Davis. He may have been a submarine captain spending his working hours in something a lot bigger, but when he was ashore, he loved zooming around in the little car, which, in 1970, cost him US$3200. (Grant has the original receipt.) When Whit was deployed, Libby got the car keys and cruised Coronado Naval Amphibious Base in San Diego Bay, an island rather like Auckland’s Waiheke.

Time moved on, as it does, and eventually, Whit was unable to drive. The vehicle was parked up in the early years of the millennium, and when he passed away, Libby wanted it out of the garage and out of her life.

Her oldest son collected Lotus classic cars but was notorious for then pulling them apart, and nobody wanted him to do that to the Datsun; her youngest didn’t want it. That left Grant’s father Rod who now lived in New Zealand. He didn’t want it, but he didn’t want to lose it either. He had an idea; he gifted it to Grant who had plans to work in San Francisco the following year.

Grant organized for the car to be looked over by a local mechanic who changed its many perished hoses, replaced all its vital fluids and got it drivable again.

In 2012 Grant and his mother flew to San Diego, picked up the car and drove it 600 miles to San Francisco, to the house of Grant’s sister who worked for America’s Cup Race Management (ACRM). It was a long journey, but the little car had a big heart and Grant looked forward to driving it again when he returned the following year to also work with ACRM as part of the race committee.

Sailing is in his blood. His father, Rod, either skippered or coached boats and crews for 11 America’s Cups, won gold at the Los Angeles Olympics, silver at the Barcelona Olympics, and during 2013, the year Grant worked for ACRM, was the head coach of Team New Zealand.

Grant was planning on being an architect, not a professional sailor. Still, he was more than prepared to contribute to his family’s association with the Challenge, so he stepped up to the 2013 event as a deckhand on a mark boat. There were two people per boat, and each boat was in charge of one mark that indicated the end of a leg or a turning point on the course.

As it turned out, it wasn’t only the America’s Cup that was a challenge; the gutsy little 240Z turned out to have a few problems of its own. Its clutch, for instance: it slipped, squeaked, and grumbled. It felt spongy when Grant changed gear. It slipped on the famously steep stretch of Lombard Street in San Francisco, with its eight hairpin turns, leaving Grant with a discomforting slide backwards to a spot where he could wrestle the car into gear again.

But he loved the 240Z, and when his Cup contract was up, he was only too happy to ship it back to Aotearoa.

Bar a new set of wheels and tyres, the vehicle was completely original and, as it was built in 1970, it met New Zealand’s vintage-car import regulations and can still be driven as a left-hand drive. Grant’s original purchase receipt allowed an accurate valuation so he could register it.

Grant with his grandmother, Libby.

It has a fair bit of rust as would be expected of a car that has lived all its life on an island and then oceanside in San Francisco. It took Woodhead Auto Electrical & Panel and Paint in Auckland two months of cutting and repairing of mostly chassis rust to bring it to compliance. Once done, the Datsun became Grant’s “sunny-day car”, the vehicle he takes out when he leaves his workaday BMW behind and hits the road; any windy road will do.

In 2015 Grant moved to Denmark for two years to do his master’s in architecture. During that time his parents were to build a new house, so an alternative garage had to be found for the 240Z. Grant found a haven at the classic car museum, Gasoline Heaven, in Carterton. But the day before he was due to drive to the Wairarapa, the car blew its fuel pump on one of Auckland’s busiest roundabouts at Greenlane. Needless to say, the car went to Carterton on the back of a truck.

Grant’s busy lifestyle has meant he has left the Datsun’s mechanical work in the hands of Woodhead Auto, although he hopes that this is the year he will take on more of the job himself. This year, perhaps, the crate of new pieces to replace some worn-out parts might make it out of storage. And then just a tiny tidy-up; some paint, rewired headlights, a tinker with the suspension and a little bit of extra love.

MORE HERE

A battered 1970s’-style Concord caravan restored to heyday looks

A battered 1970s’-style Concord caravan restored to heyday looks

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.