Kate White’s crusade to protect the Waitaki river in Kurow

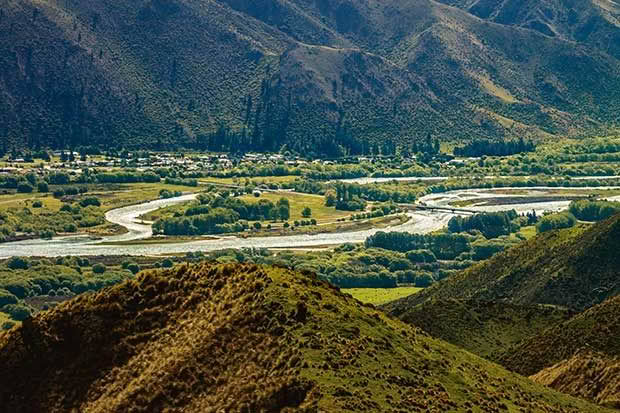

Just as the Waitaki River grinds down mountain ranges carrying them in serpentine fashion to the sea, Kate White is an irresistible force changing the face of a small south island town.

Words: Lisa Scott Photos: Brian High

Coming to Kurow hasn’t been an easy ride for Kate White.

A woman of fierce passions and phenomenal stubbornness, she wears her heart around her neck. This silver necklace – twin braids of liquid infinity – is the talismanic embodiment of the river of which she, as chair of Environment Canterbury’s Lower Waitaki Zone Committee, stands guardian and protector.

It’s also the logo of her lodge and café, Waitaki Braids.

Braided rivers are only found in four places in the world, something Kate learnt during her time with Natural History New Zealand, an experience that left her with a forever-filmic eye and the grit needed to be a female producer/director at a time when a woman in charge was as rare as a talking dog.

Kurow lies in a region kicked up by geological upheaval, where ocean floors suddenly find themselves hilltops and receding glaciers leave behind long flat buttes like ramparts.

Pressure of a different kind was brought to bear on this small town in 2002, when Meridian Energy’s Project Aqua planned to divert the river known as the “tears of Aoraki” into a separate canal for six power stations on top of the three dams already in the upper Waitaki.

“It was nothing to see 20 Prados driving around, full of university types telling us how our valley worked, and how great the project would be for our area,” says Kate.

The scheme would have produced approximately 520 mega watts of power and had considerable support from locals, one of whom, Kate believes, attempted to run her and her children off the road in the car after she started Save the Waitaki, which was seen to pose a threat to potential jobs.

With a mountain at its back and a river tickling its nose, Kurow sits in the lap of nature’s male and female energies. The river is known as Wai-para-hoanga, “water of grinding stone dirt”, referring to the glacial silt that gives it a milky hue.

Project Aqua was abandoned in 2004, six years before the Alps 2 Ocean Cycle Trail coincided with a revival bringing tourists to see the river that thankfully is still here.

Kate White, a keen horsewoman, rode into Kurow 26 years ago after marrying Pete, a beekeeper. Pete is still a beekeeper, albeit on a slightly larger scale these days. Waitaki Honey has nearly 3000 hives, selling thistle, clover and borage honey to packers who then export it around the world. Kate and Pete were BioGro-certified organic honey producers until varroa arrived in New Zealand.

Kate’s necklace was given to her by Stephen Cozens, a partner with Michelle Richardson, Peter Gordon and Michael McGrath in wine label Waitaki Braids. They were delighted to have her use it for her new venture.

Kate was also chair of the NZ Organic Exporters for a time, becoming an exporter herself, but admitting that when she sold her first FCL, “I didn’t even know what the term meant.” (Full container load.)

Fiery and spirited, from the moment she hooked then-boyfriend Pete’s tractor to one corner of a rumpty lean-to at the back of his bachelor residence, pulled it down and set fire to it, she was the talk of town. “Hear your new girlfriend set fire to your house,” teased locals down at the pub.

Cyclists on the Alps 2 Ocean trail often hitch up on the front verandah of Kate’s café and lodge which has been restored and looks just like it did when built in 1888.

“It has been a transition for me,” she says of her Kurow life, “a journey into embracing Māoridom. The local Māori have been here for 42 generations, the land is in their souls. ‘We are brothers; we are in the same waka,’ they say. But you need a river to put your waka in, a mountain to hold the snow that melts and runs down to it.”

Her insistence on the proper Māori pronunciation of place names ruffled more than a few feathers. “I fought to get on the environmental committee I now chair,” she recalls (like Boadicea one imagines, severed head in one hand).

- The möbius-like emblem celebrates the infinity of the river’s life force; a resin dog sculpture in the hallway of the lodge is by local artist Rua Pick.

- Kate likes to regale customers (and anyone who will listen) with stories about the history of Kurow.

- A resin dog sculpture in the hallway of the lodge is by local artist Rua Pick.

Has the danger passed? “The Waitaki is the only river in the country with an allocation plan; if it falls below so many cumecs they have to shut down the irrigators.”

The tangata whenua of the area, the Waitaha, might be a peace-loving people but they, and threatened species such as the wrybill, whose mother doesn’t feed it from the moment it’s born, poor mite, can be glad Kate’s a fighter.

A good keen woman, she rides with the Central Otago Hunt, swims with her horse in the Waitaki in summer, and ventures into the mountain foothills on cold mornings, the breath of horse and rider mingling in dragon plumes.

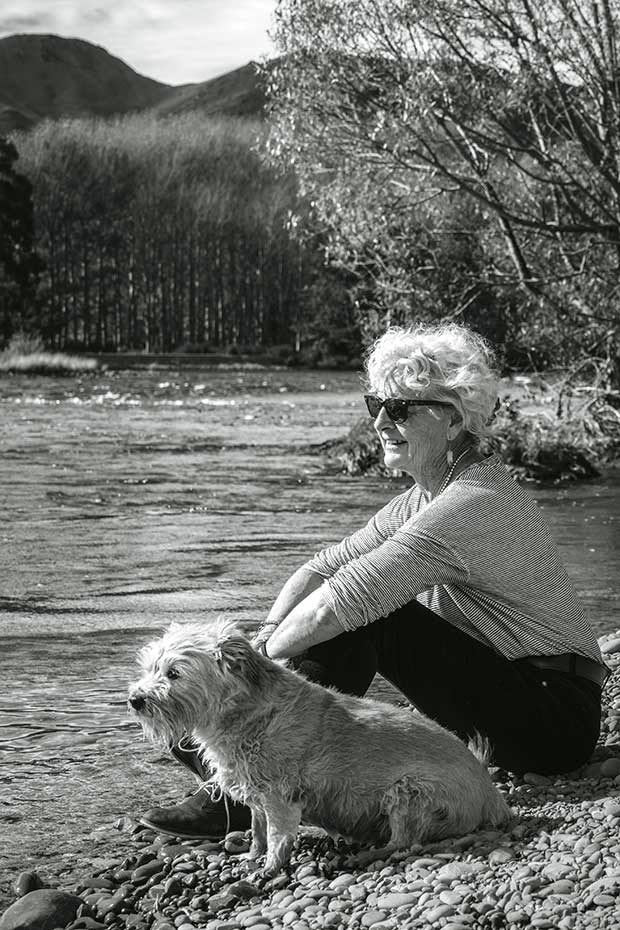

Kate, Pete and Bruno dip their toes in the river beside one of the sanctuary islands where the wrybill nests, a bird that, with its crooked beak and its parent’s penchant for kicking its babies out of the nest early, needs all the help it can get.

Pete’s bachelor pad is now a family home, seven kilometres down the road at Otiake where Mt Domett, Little Domett and Te Kohurau dominate the horizon seen from the encircling verandah. The lawn is framed by a lichen-covered layer-cake fence made from stones thrown this way and that by volcanic hands.

Half the house is 126 years old and made of local stone, the other half is 26 years old and made of rammed earth. The walls are 300mm thick.

The stone chimney was designed as a nod to those you’d see on a musterer’s hut while the French doors are one of several pairs rescued from demolition.

“I got interested in rammed earth in my twenties,” says Kate, who brought her ideas to the table when time came to build. “People said, ‘Oh you can’t do this, and you can’t do that.’ We had a really hard job with the council; in the end we got a friend to draw up a plan and did it ourselves.”

The process began with excavating 90 tonnes of earth from Pete’s brother’s farm up in the Hakataramea Valley. After three hours of hand-ramming, Kate hopped in the truck, drove to Oamaru and bought a jack hammer.

Bruno may not look like a mountain dog but he has been right to the top of Mt Domett which is in his backyard.

A collection of masks now hangs on the laboriously made walls, the first one brought from Fiji 24 years ago, the Buddha highest, serene over the rest, “as he should be”. The masks are souvenirs from many countries, some brought back from Habitat for Humanity builds the couple has participated in.

To the rear of the house is one of the first buildings in North Otago now converted into cottage accommodation and, over the fence, Waitaki Honey.

Down the road in Kurow village proper, the hill behind Waitaki Braids’ Lodge might look like a pregnant lady, feet up on the foothills of Mt Domett, but it’s not quite time for Kate to rest from her labours; she’s running the vacuum cleaner over the floor before dinner service.

- Pete and Kate harvest clover honey from hives under the big sky of the Hakataramea Valley – the inspiration for Michael Hight’s famous beehive paintings.

- Honey is exported to Japan, Italy, Denmark, Germany and the UK.

Once a general store, a hardware store, and then for years a ramshackle junk store, construction on the lodge began in August 2016, using local tradespeople. The first guests stayed in February 2017 in rooms named after tributaries of the Waitaki: Ahuriri, Hakataramea, Marawhenua.

Bruno the café ‘dog’ wanders by, his stiff back legs made of fishing twine, while mixed-media artist Rua Pick’s resin dogs bristle in the windows.

These were a celebration exhibit for the millennium and relegated to the back room of the Kurow Museum next door before Lady Fiona Elworthy suggested Kate exhibit them.

- Recycled timbers feature in the bathroom and on the stair balusters which are totara fence posts that once lined the Oamaru to Kurow railway.

- And on the stair balusters which are totara fence posts that once lined the Oamaru to Kurow railway.

- The shower in the guest accommodation is two rolls of silo iron with batts between. The round concrete floor contains pebbles from the Waitaki River.

- The kitchen is a comfortable place for coffee catch-ups with friends.

- The water bottle is Kate’s grandfather’s from World War I.

- Pete’s dad would have used these boot hooks in the days before riding boots had zips.

- Kate’s necklace was given to her by Stephen Cozens, a partner with Michelle Richardson, Peter Gordon and Michael McGrath in wine label Waitaki Braids. They were delighted to have her use it for her new venture.

- The stained-glass doors were changed to what are called “nine lights” (with nine panels of glass) by an Oamaru restoration specialist.

- Bridge beams from the old Kurow to Oamaru railway line form a pergola in the garden.

- Kate’s father, Jim, gave her the mangle.

- Popsie the horse is eight and, like a big labrador, needs a lot of attention.

- After a long walk in the hills, Pete and Bruno recover companionably on the outdoor sofa.

“They brought such an amazing energy to the building I just had to buy them and support Rua. I like to support artists; we don’t value them enough in New Zealand.”

One recent morning two people came into the café for breakfast, he the retiring CEO of Meridian on his farewell tour.

Kate, hands on hips, said, “Well, let me tell you what your company did to our small town…” He, like Kate, agreed rivers are living beings, and so precious they’re liquid gold.

And that it was a wonderful thing Project Aqua never eventuated.

Because water has a long memory.

RAMMED-EARTH REALITIES

Not to be confused with mud brick, rammed earth is a precisely controled mixture of gravel, clay, sand, cement and sometimes lime, compacted in

a removable framework to make a stone-like wall that is water-resistant, load-bearing and long-lasting.

This wall was built by Pete using stones once tossed by volcanic hands. There are 400 tonnes of stone in walls on the property.

No two rammed earth walls are ever the same. Rammed earth is particularly known for its thermal mass, storing heat and releasing it hours later

to maintain an ambient temperature.

Kate and Pete’s home has exposed trusses that come from the former Christchurch bus depot.

There are nine sets of French doors, recycled from a demolition site in Timaru. Pete and Kate scrounged some great recyclables: old fence posts used as stair-posts and balustrades, corrugated iron as bathroom walls. The recycled bridge beams are from an old Waimate bridge.

The cottage, now used by guests, is one of the first buildings in North Otago. Made of rammed earth, its walls are full of bits of old machinery for reinforcing. It was originally accommodation for potato pickers and has a sorting room below.

Kate is a brilliant project manager who knows when to delegate: “We had to dyke our house with 250 tonnes of stone wall. I lifted four rocks, went inside to get some water and never came back.”

With the experience of their own home behind them, the couple use any holiday time building Habitat for Humanity houses in Mongolia and Vietnam, Ethiopia and Fiji.

“Ten people build a house in four and a half days and it’s a really great way of seeing your charity dollars make a difference for generations. You form a relationship with the people you’re creating a home for.”

Three years ago, they were in Ethiopia. “I just loved it; it was like a movie set all the time. Africa gets under your skin and you can’t get it out.”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.