How to profit from specialty timber (from two foresters who’ve done it)

Specialty timber trees or natives can be a profitable option if you’re planning to plant out more than a hectare. Two long-time foresters share how you can get the best out of your block, based on their 30 years of experience.

Words: Emma Rawson Images: Simon Young

Who: Gabrielle and Andrew Walton

Where: Summerhill Forest, Papamoa Hills, 10km south of Tauranga

What: 100ha forestry plantation of specialty species including cypress (Cupressus lusitanica), Tasmanian blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon), Victorian ash (Eucalyptus regnans), and Sydney blue gum (Eucalyptus saligna)

Gabrielle and Andrew Walton’s new timber home smells of sap and sunshine.

The house took two years to build but was decades in the making. They grew nearly every single plank of wood used in their home on their farm forest, Summerhill, in the nearby Papamoa Hills.

The exceptions were redwood, sourced from an 80-year-old plantation in the Waikato, and the plywood that sits behind the redwood for waterproofing.

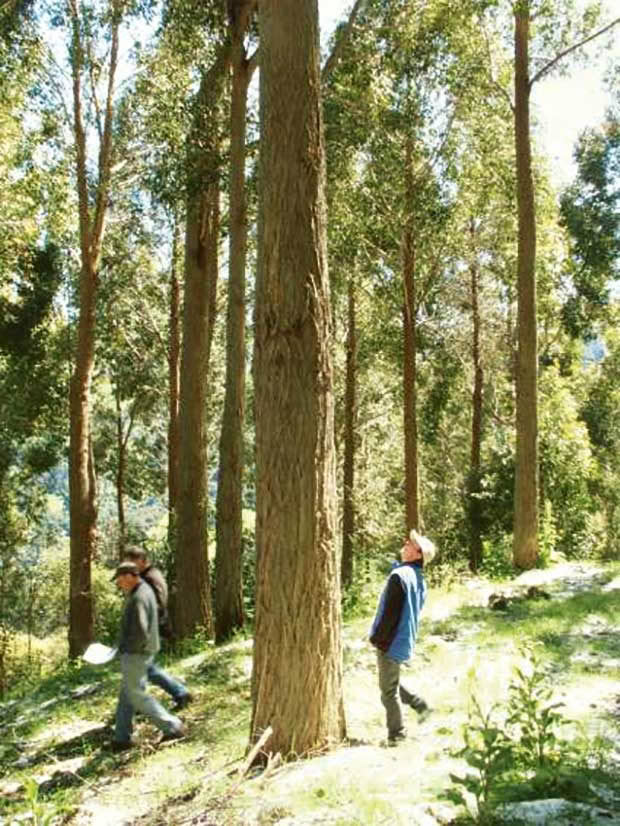

This image and left: Gabrielle and Andrew Walton in their specialty timber forest, near Tauranga. The couple are advocates of growing niche trees under a continuous cover policy, where only select trees are felled as they reach maturity, leaving the rest of the forest intact.

All the accolades the house has received don’t come close to matching the satisfaction Gabrielle and Andrew feel seeing the manifestation of 30+ years of hard graft. It has taken years of planting, thinning, pruning, and relentless weed control on land so steep, the forestry workers’ calf muscles are in constant extension.

In 1984, Andrew and Gabrielle created a joint forestry venture with her parents, David and Cloie Blackley. Specialty timber was a bit of a gamble in a country where 90 percent of commercial forests are Pinus radiata.

The Walton’s house, designed by architect John Henderson, won a prize in the NZIA Waikato/Bay of Plenty Architecture Awards, and a highly commended in the 2018 NZ Wood Resene Timber Design Awards.

But landscape architect Gabrielle was determined, insisting that they plant a mix of exotics: Cypress (Cupressus lusitanica), Tasmanian blackwood

(Acacia melanoxylon), Victorian ash (Eucalyptus regnans), Sydney blue gum (Eucalyptus saligna), Tasmanian blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon), redwood, poplar, alder, and the fast-growing Chinese native, paulownia.

“We didn’t know for sure there would be a market for specialty timber 30 years down the track, but I also didn’t want to put all my eggs in one basket,” says Gabrielle. “New Zealand has a ‘pine mentality’, and the whole forestry and building industry are geared around a commodity crop like pine. But that’s short-sighted in my opinion; New Zealand needs to diversify.”

Forestry contractor Caleb Davies working on cypress in the Walton’s forest.

The cypress, Tasmanian blackwood, Victorian ash, and Sydney blue gum at Summerhill are all coming into maturity, but the specialty timber industry is still in its infancy. Gabrielle and Andrew sell their wood for a premium through their website, marketing it directly to architects and designers.

One big challenge is the NZ building code, which is primarily geared towards treated pine and, to a lesser extent, douglas fir. Homes constructed with specialty timbers often require a special building permit called an ‘alternative solution’.

Structural grade untreated larch and untreated heartwood from the cypress species are the only specialty timbers written into the building code for framing.

NZS 3602 allows untreated heartwood from redwood, western red cedar, cypress species and New Zealand beech for outdoor use in stairs, decking, and handrails. Specialty woods must be proven to be fit for purpose to be used in a NZ building, despite many such as eucalyptus being naturally strong and durable.

Gabrielle Walton with contractors Caleb Davies and Rob Brown. Gabrielle often has to book forestry teams to work off-peak times, when they are in-between big contracts, as the Walton’s work is considered a small job.

When it came to Gabrielle and Andrew’s house, they had to use data from Australia to prove their eucalyptus could be used in the build.

“It was more work but the timbers we used in construction are naturally stronger and as durable as treated pine,” says Gabrielle. “The good architects that know this aren’t deterred.”

GABRIELLE’S TIPS

The Waltons and other specialty timber growers are keen for more people to join the industry to help bolster the supply chain. Small exotic timber forests are well suited to lifestyle blocks. Their high-value makes them a good use of space and worth the time.

Gabrielle’s tips for getting it right include:

Right tree, right place, right purpose

The motto of Crown Research Institute Scion is good advice. Do your research on which species are suited to your region.

“The Farm Forestry Association’s website is a great resource and try visiting a Farm Forestry field day to meet other growers in your region.”

Access is critical

“Don’t put specialty timber species way out the back of the farm,” says Gabrielle. “Grow them somewhere that’s easily accessible as you’ll need to visit them often.”

Think about extraction from the beginning

It can be tempting to plant in marginal areas, but consider how you will fell and remove logs before you start planting.

“You might need to bring in big machinery or trucks.”

Think about height

Find out how tall the trees will grow. Consider your views and your neighbours’.

Who: Dean Satchell

Where: Kerikeri, Far North

What: 150ha

Dean Satchell describes himself as a hard-nosed commercial tree grower.

“I’m here to plant trees, not to hug them,” he says. “I’m also here to produce revenue from them.”

He has been trialing different exotic tree species on his forest farm near Kerikeri for 30 years, recording many of his findings on the Farm Forestry Association website.

“We need more of these exotic species planted for product development to take place,” he says. “Otherwise, it’s a niche market. I want to see more plantation success stories because I’ve seen so many growers fail.”

One spectacular example was a vast plantation of 100,000 trees in the Waikato which didn’t get established after an expensive helicopter spray failed to kill grass growth. That was a fundamental mistake, says Dean.

A slice of a 10-year-old blackdown stringybark (Eucalyptus sphaerocarpa), one of Dean’s favourite timbers. He notes its high heartwood content (the darker wood in the middle), even at this relatively young age.

“You need to check your forest regularly. Had that grower checked their plantation, they would have seen the spray hadn’t killed the grass and weed control was needed. A forest plantation should never be a case of ‘out of sight, out of mind’.”

While Pinus radiata will grow almost anywhere in NZ, Dean says they’re not the best crop for a small farm forest. He’s in favour of continuous-cover forestry, where only a few large trees are removed from a forest, leaving smaller trees to grow on.

“Pinus radiata is all about big business. There are big logging trucks and big factory production. The scale of the industry doesn’t suit people who might only want a few trees felled at a time.”

DEAN’S TIPS

Choose the right species

Specialty timber trees are very site-specific and require research before planting. For example, there are 600 different varieties of eucalyptus, each one adapted to a specific micro-climate.

Dean has had a lot of success growing several of the stringybark varieties. He says the hardwood trees are as easy to grow as pine, but the timber, often used for decking and flooring, is much more valuable.

When stringybark eucalypts are planted close together, they self-prune, and force each other to grow upwards. “It’s a trade-off,” says Dean. “You have higher costs at the start with the plantings, but you negate those costs with lower pruning and silviculture costs down the track.”

“Do the research on your location before you plant. Members of the Farm Forestry Association are keen to give advice, farm forestry field days are well worth attending.” Upcoming field day dates are posted on the association’s website and in its newsletter.

Control pests

Kill possums, hares, and rabbits before planting, or they will munch on seedlings. Make sure fencing is good enough to keep cattle at bay. Weed control or ‘releasing’ is critical, particularly in the first few months

“Weeds will grow faster than trees,” says Dean. “If you plant trees and forget about them, the weeds will smother them. The ideal time for releasing is that moment when the weeds are starting to compete with the trees, but you’re not struggling to find the seedlings.”

Winter is the best time to plant

“Planting times can be site and species-specific, but generally, forest farmers will spray for weeds and plant in winter, and release in spring and summer.”

Be aware of drift

Be wary of spraying paddocks adjacent to plantations – don’t allow chemicals to blow onto trees.

The first 10 years are the hardest

Species such as eucalypt and cypress will take a decade to reach canopy stage. They then mature for at least another 20 years but require a lot less maintenance.

“People often approach planting trees with gusto and then they move onto the next project,” says Dean. “For a successful forest, you need to follow through with pruning and thinning, selecting the best trees. It’s hard work for 10 years.”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.