Hut on the hill: Explore this wee hut on a 1400ha farm in north Canterbury

This couple has built a first-rate life among the drylands of north Canterbury, spiced up — as if it were needed — with classic cars and a cottage with a view that rolls on forever.

Words: Lee-Anne Duncan Photos: Dan Kerins

Hands tell a story and Andy Fox’s are definitely farmer’s hands. Callouses and roughened skin speak of years of working the land; the dirt under his nails early on a Saturday conveying that every day is a workday.

His wife Kath has “nice, lawyer-y hands”, she says, even if those have been pressed into unexpected services since she came — nine years ago — to Foxdown, a farm inland from the Greta Valley in north Canterbury. “Turns out I’m quite useful at lambing. I think ewes would rather have my hands helping them than Andy’s big hands.” Quite.

Further evidence that there’s no rest for farm folk is the sawdust that cloaks their clothes. This time it’s because they’ve just popped over to replenish firewood stocks at The Hut — actually a brand-new cottage with views of rolling-hill country in the Culverden Basin.

- Life on 1400 hectares farming romney sheep and hereford/angus-cross cattle keeps Kath and Andy Fox busy enough, but the couple also hosts visitors at Foxdown Hut, high in the hills of their north Canterbury station. For Kath, who’s also a lawyer, the hut gets as close to camping as she’s comfortable.

- “The hut means people can be in the middle of nowhere but still be in luxury. If the weather’s bad, it doesn’t matter because there are enormous doors out onto the view. And there’s the fire, and a proper toilet and shower.” And don’t forget the perfectly positioned outdoor bath from Stoked Stainless.

“We call it The Hut because we don’t want people to be underwhelmed,” says Andy. Unlikely. Foxdown Hut is a one-bedroom retreat in the middle of the 1400ha sheep and beef farm that Andy’s family has owned for four generations. With his three sons also keen to farm, the fifth generation is in the planning.

The hut, which is available to visitors on Canopy Camping, is the latest occupation keeping this couple busier than a hill-country huntaway mustering sheep.

Although Kath was a townie living in Lyttelton when the pair met, Andy’s familial connection to Foxdown goes back to 1877 when his great grandfather Charles Dillworth Fox bought his first piece of farmland. In 1937, Charles’ son Alex built Foxdown’s six-bedroom farmhouse, complete with art deco flourishes.

Despite carpentry skills acquired in his youth, Andy (who holds a piece of barbed wire unique to Foxdown) left the hut’s construction to others. But he did the landscaping, built the deck and was at Kath’s beck and call to knock up what else was needed. “I spend a lot of time on Pinterest, and I can say, ‘Andy, can we do this?’” Kath says. “The next minute he’s knocking up just what I need.”

It’s the house Andy grew up in and has mostly lived in since, allowing for time at boarding school, university, and an OE that took him to the big skies of Montana as a ranch-hand, then the grey skies of London as a finishing carpenter.

He enjoyed carpentry and says those skills came in handy when building the hut — he did the outside construction, including the deck, fencing, retaining walls and landscaping.

But as a born-and-bred farmer (and even as a finalist in the 1993 Young Farmer of the Year), Andy’s primary skills are agricultural, honed to those essential for a hill-country farmer on land that might be green for months but can dry to brown in a matter of weeks.

- The pallet coffee table is not Andy’s work — Kath found it on Trade Me.

“Usually by New Year’s, it’s pretty brown around here,” he says. “Although, we like to call it ‘golden’,” corrects Kath, showing the optimism also essential to farm life.

“It’s just part of our farming operation,” says Andy. “Are the seasons getting drier? They’re certainly getting warmer. I can remember an Anzac Day as a small boy with frosts hard enough we could skate on puddles that were frozen solid. These days, we regularly get to May without a frost at all. It’s making our winters easier, but in turn, summers are more challenging. Every business has its issues and dealing with the dry in north Canterbury is just one of ours.”

- Visitors are more than welcome to arrange a ride in one of Andy’s dozen (or so — Kath suspects he’s hiding some) classic cars. The usual pick is a 1927 Cadillac that sports the gauges from Al Capone’s car of the same make. “Unlike some people who collect cars, Andy drives all of his,” says Kath. “One of Andy’s cars has a full pull-down bar in the back. It has all the glasses and decanters and everything. That’s my style.”

While devoted to the farm, Kath and Andy both balance on-farm time with off-farm activities. Kath’s lawyering (banking and finance) takes her 80 kilometres into Christchurch most weekdays. Andy serves in governance roles on industry boards — the Wool Research Organisation and Wool Industry Research — both of which research new, often high-tech, uses for wool.

He is also involved with charities, including the Waikari Medical Centre, North Canterbury Farmers Trust and EB Milton Charitable Trust — the latter two set up to benefit young rural people. Before that, he spent nearly 20 years on the board of Silverfern Farms and the Meat and Wool Board.

Foxdown Hut is four kilometres from any other light source, which makes it a stargazer’s delight. Many visitors are inspired to photograph the sky in its purple and silver glory, including the image taken by Arun Brahmaniya.

For Andy, off-farm interests are a deliberate decision. “Farming can be quite solitary, and I enjoy people. I love farmers, but when you live in the country, your next-door neighbour does the same job as you, and when you go to the local school, a lot of the other parents are also farmers. It’s nice to have hobbies or business interests that take you away from the farm.”

Andy’s hobbies also attract people to the farm. Among its buildings is a purpose-built garage-cum-museum for his classic car collection, which hosts hundreds of visitors each year. Inside is an impressive array of mostly restored vehicles, all roadworthy and easily able to cope with the four-kilometre shingle road leading to Foxdown.

Former townie Kath is more than happy to cuddle up to this massive four-year-old hereford/angus-cross bull. But, then, who could be afraid of an animal that answers to Boo Boo? “His name is supposed to be Lemony Snicket, as he suffered a series of unfortunate events when he was only a day or so old, but we call him Boo Boo. I hand-reared him and used to lift him into his little shed at night. He’s grown a bit since then, but he’s still very biddable — for a bull,” says Kath.

While on the farm, as well as perhaps enjoying a pre-arranged classic car ride, visitors are encouraged to take a three-hour walk across the land, starting at the drystone stockyards built by Andy’s great-grandad in 1890, then hiking to the top of Mt Alexander. Andy takes every opportunity to share his farm’s history and farming’s economic contribution to visitors.

“Younger generations don’t have much of a connection to farms any more. We want them to understand farming and to buy what we produce. So I like to explain what we do and why and help them understand the difference between intensive farming and how we farm here.”

“Some farmers don’t like people on their property, but Andy understands the privilege of being here, and he loves sharing it,” says Kath. “That does help bridge the town-country gap.” It’s a gap Kath herself was more than happy to bridge when she met Andy 11 years ago.

“My dad has an E-type Jaguar, and his wife didn’t want to go with him on a car run, so he asked me. I thought, ‘Not really,’ but I was single at the time and I had this rule that I had to accept all invitations so I found myself saying, ‘Oh, that would be lovely.’ I thought it was going to be a lot of old fogies with their cars, but then this red Corvette came up the drive and did a doughnut. I thought, ‘That’s a bit interesting,’ and then Andy hopped out and it got even more interesting.”

Andy’s great-grandfather built the dry stone stockyards in about 1890. “There’s probably about a ton of rocks for every metre of wall, and the walls run for 100 metres,” he says. The Kaikōura earthquake brought down sections of the walls, so with the help of YouTube, Andy added drystone masonry to his set of skills. “There’s quite a science to it. It’s not simply putting one rock on top of the other.”

At that time Andy was still feeling raw from his marriage breakup and wasn’t keen on going on the run, so he took a “drinking partner who’s good company” along for the ride. The complication was that when Kath saw his male mate — who eventually married them in the drystone stockyards in 2016 — get out of the Corvette’s passenger side, she assumed she wouldn’t exactly be on Andy’s radar.

Meanwhile, Andy spotted Kath but thought her dad was her husband. Luckily, they quickly cleared up their misconceptions and Kath rode home in the Corvette, not the Jag.

Andy’s three sons — George (26), James (24), and Tim (23) — were welcoming. “They’ve always been amazing to me. I’m a good cook, and that helps with boys,” says Kath, who gave up her legal partnership for the country life. “When I announced I was off to marry a farmer and wouldn’t be coming to town as much, I think everyone thought, ‘What the hell?’ I still work in the city, but I have a balance. I am like a pig in the proverbial here. Moving to the country was the best thing I ever did.”

Pickle is the couple’s six-year-old kune kune who enjoys more house privileges than the dogs, despite her explosive nasal expulsions, which inspired the name “Foxdown snot rocket” of a cocktail created by Kath. It’s made with lime, cucumber, mint, sugar syrup and Bacardi blitzed in the blender with lots of ice.

Opening Foxdown Hut means Kath and Andy can now share their love of the country even wider. The idea began in less than ideal circumstances in January 2019. “Andy was couch-ridden, horribly sick with leptospirosis, but his mind kept thinking about projects. We’d talked about building a cottage, but I thought it would never happen.

“Next minute he had called an architectural draftsman and was organizing the excavation. That’s what I love about Andy; he’s a doer,” says Kath.

In true country style, the site was leveled by a local in payment for Andy officiating at a wedding. (Andy’s also a celebrant, a qualification he attained at the request of a to-be-married niece.) In June 2020, the first official guests were welcomed to the hut, designed to be like “camping without the discomfort”.

- Kath’s well-equipped kitchen is evidence of her culinary skills. She’s a dab hand at cocktails, too, including what’s become known as a “Foxdown snot rocket”.

- Kath with her young dog, Hash. “He’s a star,” she says.

“We’ve always had a lot of visitors here, and I understand why people love coming. We probably take some of this for granted, but it seemed that if people like coming out here, let’s make life easier for them and give them an experience,” says Kath.

It’s an adventure neither Kath nor Andy ever tire of, and while the farming life is just life as Andy’s always lived it, Kath continues to surprise herself with new skills — including playing midwife. “It’s satisfying when you pull out a lamb, and the ewe starts licking it. And sometimes I get to muster a paddock on my own with a dog.

“We have a new dog, Hash. He’s still learning, and I’m learning. There are few things better than being out on the hill with a dog. It’s pretty peaceful out there.”

CAR STORIES

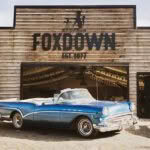

Ideally, classic cars don’t get too close to barbed wire, but Andy Fox’s museum at Foxdown exhibits his fascination for both. The purpose-built garage houses a dozen classic cars he’s sourced worldwide, including his latest restoration, a 1937 Cord.

There’s also a 1958 Edsell, a 1927 Cadillac, which sports the gauges taken from Al Capone’s actual car, and a 1936 Cadillac Roadster. Many of Andy’s cars are named for people associated with them. The Cadillac, for example, is Eliot, named for Eliot Ness, who brought Capone to justice.

- A 1957 Buick Century convertible glints outside the Foxdown Museum.

- A 1936 Cadillac convertible coupe with the plate Fox 2 is ready to hit the road.

- The beautiful dashboard belongs to a 1937 Cord.

One of his favourites is Lester, a 1939 Studebaker, which Andy has owned for 25 years. Lester is unrestored, unlike most of the other cars, but it’s a deliberate choice. “When I first drove Lester in that unrestored state, probably 80 per cent of people said, ‘Oh, you’re going to restore him?’ and 20 per cent said, ‘Leave him the way he is, with that nice patina.’ But now that’s reversed. That natural ‘barn find’ car is almost more interesting than a fully restored car.”

There’s also a 1922 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost the pair shipped to Europe in 2013 to be one of 100 Ghosts re-enacting a tour of Europe’s highest passes, originally staged a century before to show the reliability of Rolls-Royce’s vehicles.

When cleared of cars, the building is also useful for holding “drought shouts”, a party put on to bring often-isolated farming people together to lift their spirits during dry and challenging times.

The car excited a lot of interest. It was even used in a wedding in Le Quesnoy, where the Fox family has a lasting connection dating back to World War I — Andy’s grandad was the first soldier up a ladder in a Kiwi-led action to liberate the walled French town.

While a dozen cars seem a lot — and Kath isn’t entirely certain that’s the full count — Andy sees no problem. “I had a guy come visit who had 400 tractors, so I don’t think I’m too bad.”

More curious than classic is Andy’s collection of more than 100 types of barbed wire. Yes, there are that many, and more — not just the Iowa 75mm patent barb most farms use today.

- Andy works with youngest son Tim on “Lester”, a 1939 Studebaker President. Cars are a hobby that’s easily incorporated into other aspects of life, he says. Handily, it’s also the pastime that brought Andy and Kath together — they met on a car run.

- Inside the museum, Andy consults his barbed wire guide, the Barbed Wire Bible.

Andy sees romance in the spiked specimens for the part the wire played in taming the American West. “When it was invented in the mid-1800s, it spelt the end of the cowboy as the ranchers could cheaply build fences to confine their animals. There was a real scramble back when it first started as people could see it was a good thing, and because transportation was expensive, lots of areas made their own.

But only a few manufacturers survived. It was probably an invention as impactful as the silicon chip. I studied in the United States in 2003, and I picked up about 30 samples then, and we have a rare sample here that’s not used anywhere else.”

Kath also sees the romance and even wove a bit of barbed wire into her hair for their wedding. “Some of them are more like jewelry than barbed wire,” she says.

MORE HERE

Glamping at Wainamu: Jim and Anna Wheeler on transforming the camping experience

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.