How to get started in sharemilking

If your cow has the right temperament, she can turn grass into milk, steak, and money.

Words & images: Sheryn Dean

‘Sharemilking’ on a lifestyle block doesn’t mean the same as it does in the commercial dairy industry. It’s where you run a house cow, which provides milk for you and a calf. There’s always enough milk to share. When you don’t need it or can’t be bothered milking, the calf converts it into meat to eat or sell at a profit.

It sounds idyllic. Mum and babies frolicking around the paddock, you skipping down to the paddock with your pail in a picturesque milk-maid scene.

The pluses of sharemilking

While I’ve found little opportunity to skip anywhere, sharemilking with a dairy house cow is a great way to farm, and produce milk for the household.A good dairy breed will produce a lot more milk than one little calf can drink, up to 15-20 litres a day. A newborn calf needs just 4-5 litres.

You can line up with a bucket from Day 1 and turn colostrum into puddings. From Day 5 onwards, you’ll get more than enough creamy milk to make cheese, cheese, and more cheese.

Getting extra calves to feed off a house cow takes a bit of time and effort initially, but it pays off. Calves raised on a cow are healthier, larger, and have a better-developed digestive system than those raised on milk powder. You also get meat or money if you sell the animal, and all at a fraction of the cost and time of raising them by hand.

Sheryn’s tips: Either choose a lower-producing breed such as a Dexter cow (10-12 litres per day). However, when the calf is bigger and drinking more, you’re going to need to save several days worth of milk to get the 10 litres you’ll need to make a cheese.

Or go with my preference, a high-producing dairy breed. She’ll raise her own calf, and seven foster calves throughout a spring-autumn lactation.

The pitfalls of sharemilking

Don’t let the following put you off, but you need to know this before you start.

• Dairy breeds such as Friesian and Jersey produce way too much milk for one little calf. There will be times you’ll need to milk mum to release udder pressure, whether you want milk that day or not.

• Other times, a cow may ‘hold’ their milk for their baby. This means they physically don’t allow (or ‘let down’) any milk into the udder. Worse, she just won’t let you touch her teats at all.

• The calf can cause the teats to crack. They might become so sore your cow will kick out as soon as you touch them.

• If you’re not organised, the calves will drink her dry, even if you separate cow and calf the night before. Calves can be ingenious at finding a way to drink through fences and barricades.

It’s all about the cow

Whether you can foster calves depends on your cow’s temperament. In my experience, older cows from a commercial dairy herd tend to accept strange calves. They’re certainly better at it than the cherished, specially bred Jerseys I raised from calves to be my house cows/foster mothers.

But it depends. Farmers I’ve spoken to who foster calves onto Herefords tell me they’ve found the opposite: if they don’t train a heifer to take on foster calves when she’s young, she won’t do it as an adult.

I’ve never met the perfect house cow/foster mother. In my experience, there are two types:

• great mothers that accept any nuzzling newborn, but refuse to ‘let down’ their milk for me; or,

• they’ve been happy for me to take whatever milk I want, but won’t let foster calves within 10 feet of them.

HOW TO FOSTER CALVES ONTO A RELUCTANT COW

I’ve tried everything:

• sourcing calves (aged 4-14 days) just before my cow’s birthing day and rubbing her own calf’s birthing fluids over them;

• removing her calf;

• keeping all the calves, including hers, separate from her overnight, then supervising feeding in the milking shed the next morning.

I did hobble a reluctant cow once, but she needed careful supervision at feeding time. Eventually, I found it easier and safer to hold her halter while calves were feeding.

My method

Over the years I’ve found it best to:

• keep the cow separate from the foster calves for the first few days;

• restrain the cow in a milking bail in a pen twice a day;

• milk the cow;

• let the foster calves into the pen to feed through the sides of the bail.

After a week or so, I start holding her by the halter in the paddock while the foster calves feed. Most calves are pretty determined, especially when they get hungry, and quickly figure out to latch onto a spare teat when a cow’s own calf is feeding.

Sheryn with house cow Miss Sue and her calf Sapphire. A well-fed Jersey can easily give you 2-4 litres of milk each day, and have enough left over to feed two calves.

A good foster mum will stand happily on her own while four calves bunt her and fight each other for her milk. Depending on the maternal nature of the cow, after a couple of days of supervision, mum and the calves get the idea, and you can leave them to feed on her as they need it.

Sheryn’s tips

• Source calves of a similar colour to a cow’s own calf;

• Cows seem to accept new calves more readily at the beginning of a lactation.

WHY COWS HOLD MILK AND WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT

Some cows have a strong maternal instinct. They’ll charge a dog from two paddocks away, and fall in love with any calf, anytime. But they won’t accept you. They’ll kick and perform in the milking bail and won’t ‘let down’ their milk.

Cows can control their milk flow. It’s usually stimulated by calves suckling or when you wash the teats with warm water. But if she doesn’t like you taking her milk, she can stop it from flowing. I’ve tried a variety of methods to encourage a cow to let down her milk, including:

• wet, warm flannels;

• singing;

• swearing (definitely didn’t work but I felt better);

• oxytocin.

Oxytocin is a hormone that, when injected into cattle (or other livestock), contracts muscles in the mammary gland, which induces milk let-down. It usually takes one or two doses to get the cow into the habit of releasing her milk when she comes into the shed.

My first house cow needed it every year at the start of milking. Her head would hang low, her ears would droop, and she’d look relaxed. Serenely stoned. But I wasn’t happy about it.

Eventually, I altered the milking bail. The calves would be penned on one side and could reach through the bars to suckle two of her teats. I would frantically milk the other side and try to ensure there was no calf dribble in the bucket.

A friend who wasn’t confident at hand milking had a young heifer who would viciously kick out when she tried to milk her. Even her calf wouldn’t suckle when her mother was in the bail. She tried lots of tricks but eventually resorted to buying a one-cow milking machine that solved the problem.

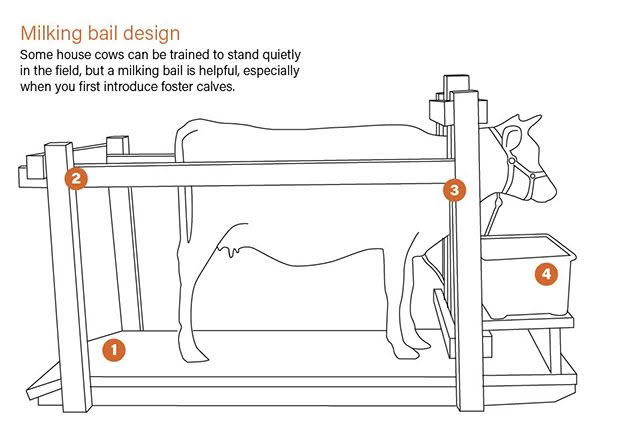

The milking bail

This bail has one rail, but you could have two for more strength. The rails should be up high, so you (and the calves) have easy access to the udder. A rope, chain, or board at the rear stops the cow from backing out. Sometimes you may need to loop a rope around one rear leg if she has a habit of kicking out when you first touch her.

If the bail is open on both sides, foster calves can feed from behind (between the cow’s legs) or from either side. This bail features:

1. A wooden floor, so the cow is slightly raised, giving you easier access to the udder. It’s also on skids so it can be towed into a pen, paddock, or shed.

2. One or two rails, which are higher than udder height.

3. A head bail to keep the cow in place.

4. A trough for feed and supplements is a good enticement for a cow, so she’ll stand quietly during milking

HOW TO RAISE 8 CALVES ON ONE COW

I’ve always had high-producing dairy breeds (Jerseys or Jersey-Friesian crosses). If they have ample feed and excellent care, they can produce enough milk for a household and raise eight calves in a year.

I would source three calves when my cow birthed in early spring. Nights are still cold at this time of year, so I’d initially keep the three calves in a shed to give her time to get used to them. After about a week, they’d free range and feed in the paddock with her and her calf. Two or three times a week, I’d separate mother and calves overnight so I could milk her the next morning.

After 8-10 weeks, I’d wean the three foster calves and add two new foster calves. They’d learn to drink when she fed her own calf in the bail; after a couple of weeks, they could be let out together.

Taking on a third pair was always more complicated. It’s harder to find newborn calves in December as it’s out of season for dairy farms. I’d also have to wean her own calf, otherwise it would overpower the young ones and drink all the available milk.

My house cow, with marginal maternal instincts, was also less willing to accept foster calves later in her lactation. In my case, I had to use a collar and tie her to a post, then stand with her while they fed, twice a day at the start, then once a day as the calves got older.

Sheryn’s tips

• Always have fresh water available to calves. It needs to be in a bucket, positioned off the ground (to avoid accidental contamination from manure), and easy to remove for regular, thorough cleaning.

• Use a teat cream or emollient salve on a cow’s teats after the calves have fed to keep the skin soft and supple, so you avoid painful cracks.

TIPS FOR BUYING & CARING FOR FOSTER CALVES

1. The one best place to buy calves

Bringing new calves onto your block is a big biosecurity problem. The main risk is disease, such as the highly contagious rotavirus, which is almost impossible to eradicate.

The best option is to source calves directly from a commercial farmer. Look for one who won’t let you into their calf sheds, a sign they take biosecurity seriously. Buying directly also reduces the risk of a calf picking up diseases or becoming stressed during transport or in sale yards.

If you can establish a good relationship with a farmer, offer to pay them extra to keep the calf until it’s 10 days old instead of the standard four. That extra week makes it much easier for the calf to transition onto a foster cow. Don’t buy the runty bargain. You want the strongest, healthiest-looking calves with shiny hair and bright eyes.

2. Take care when changing their diet

It’s essential to transition calves onto their new diet gradually.

• Check what the farmer is feeding them:

– if it’s milk from their shed, ask for a 20-litre bucket of it when you collect the calves;

– if it’s milk powder, organise to buy some from the bag they’re using (and get instructions on the correct powder to water ratio and the amount to feed).

• If you’ve brought the calves home late in the day, skip the evening feed and let them settle in a warm shed with access to water.

• The following morning, warm up and feed them two litres of the farmer’s milk. That night, feed two litres of 50% milk (or colostrum) from your cow and 50% of the farmer’s milk, with a cup of home-made yoghurt mixed in. Watch their stomachs while they feed and time how long they take to finish.

• Increase the ratio of your cow’s milk over the next day or two.

• Once they’re drinking only your cow’s milk, separate her calf from her overnight. You want hungry calves and a cow with

a full udder for the next morning.

• Put your cow in the milking bail and introduce the calves to the teats. Get them to suck on one of your fingers, bring it up close to a teat and they’ll soon get the idea.

• If the cow kicks, tie one rear leg to a post (with an easy-to-release knot).

House cow Shadow with her fosters calves. Jerseys make great housecows and foster mothers. They’re small, light (in comparison to a Friesian), docile, easy to handle, and who can resist those beautiful brown eyes?

• Watch and time how long the calves drink to ensure they don’t overfeed. Too much milk will give them nutritional scours (see box, above right).

WHAT IS NUTRITIONAL SCOURS?

Main symptom: bright yellow or white (undigested milk) watery scours

Other symptoms: depression/lack of energy, dehydrated, sunken eyes, wet under the tail, dry muzzle, high temperature (39.4°C+)

Cause: overfeeding, stress (transport, new surroundings,new people), change in diet (switching too fast from one to another), environment (sudden change in temperature, overcrowding, too humid)

Treatment: call your vet immediately for advice – don’t leave it until the next morning,

or a couple of hours. Dehydration from scours can kill a calf very quickly, even if it looks healthy and is still drinking. Typically, treatment involves stopping milk feeds for 24 hours and replacing it with an electrolyte drink

Warning: If scours are dark or bloody, or the calf is looking sickly or dehydrated, it’s an emergency and you need a vet immediately.

MORE HERE