20+ low cost pig feed options to help grow tasty pork

An Iberian pig in Spain. These pigs are ‘finished’ on a diet of acorns which gives the meat a unique flavour.

The price of feed can be high, but Sheryn has perfected ways of growing the tastiest pork at very little cost.

Words: Sheryn Dean

‘You are what you eat’ holds true for pigs more than any other animal. A friend claims the best pork is from a pig that slurped a flagon of red wine for its last supper. Personally, I find slurping the wine myself makes anything taste great.

But the feed your pig is ‘finished’ on – what it eats in the last three months of its life – affects the meat’s flavour and nutrient levels. The world’s ultimate ham is said to be jamon iberico de bellota which sells for US$100 a pound (about NZ$320 per kg). It’s a dry-cured ham from Iberian pigs (they resemble a Captain Cooker crossed with a Black Devon) which spend their final months grazing on acorns in Spanish forests.

WHY PORK IS RED MEAT

Legally, pork is a red meat (determined by the quantity of myoglobin, the iron-containing protein that stores oxygen). It was termed a ‘white’ meat for marketing purposes.

Pig feed pellets are available from rural supply stores and are an all-round, nutritious feed, including protein. I prefer not to feed manufactured or processed food as it negates the benefits of my meat being home- grown. Barley is probably the best all-round grain for pigs. Feed it crushed or steeped in water to soften. Meat meal provides good protein.

Here are the other feed options I use to give the meat great flavour, all grown myself.

Oaks

A pig can eat about 8kg of acorns each day.

Finishing a pig on fresh acorns will add a nutty taste to the meat.

Quercus robur acorn.

Acorns can be gathered and stored in a well-ventilated place. However, the longer they are stored before feeding out, the less effect they have on the flavour of the meat. Grazing other livestock on small amounts of seasoned brown acorns and the leaves can be beneficial.

Quercus candicans produces acorns a bit earlier than the common English oak (Quercus robur) which is a quick-growing and prolific producer of acorns. The acorns of the white oak (Q. alba), Chinese white oak (Q. aliena), and evergreen holm oak (Q. ilex) have low tannin levels and are the sweetest and tastiest acorns. These are the ones used to make coffee and flour substitutes.

The evergreen cork oak (Q. suber) is slower to produce but has a sweet, low-tannin acorn. It drops later than the other varieties, extending the season. In 25+ years, you might be able to harvest your own cork too.

Scarlet oaks (Q. coccinea) and red oaks (Q. rubra) are worth including for their autumn colours. The scarlet oak has acorns early in the season. The red oak has a low-tannin, less bitter acorn.

Warning: livestock can suffer toxicity or death if suddenly able to eat large amounts of fresh acorns. Prevent livestock from having access to oak trees in early autumn, particularly if a storm is threatening which will cause large amounts of green acorns to drop.

SHERYN’S TIPS

• If you’re planting oaks for pigs, consider a range of varieties to extend acorn availability throughout the season.

• If trees are in an area with vehicle access, consider planting them close together (1.2-2m apart) – you can thin them for firewood after 10 years.

• If you remove the bitter tannins, acorns are a highly nutritious food for humans, containing lots of vitamins and anti-oxidants.

Nuts

Planting nuts for pigs is a long-term plan but the trees will provide autumn food, shade, and shelter for centuries. Nut production can begin after three years but most trees take 7-10 years to come into full production.

The English walnut is the most common edible variety. The Japanese walnut (a weed pest in some parts of NZ) and the butternut or white walnut are also edible and enjoyed by pigs.

Single walnut trees will produce quite happily by themselves, but production will increase if there is another variety planted as a pollinator.

Chestnut trees grow well around my Waikato area and produce vast amounts of chestnuts. However, my pigs decline to get their noses pricked by the prickly burrs – I sort the nut from the burrs myself. I have seen sheep learn to stomp the burrs open to extract the nuts and I am sure pigs less spoilt (and hungrier) than mine would work it out.

Chestnuts in their spiky burrs.

A single, self-pollinating chestnut variety will produce nuts. However, a tree will produce substantially more if a second variety is planted close by as a pollinator.

Hazelnuts are a smaller tree. They can be pruned into a single-trunk tree but left to themselves will form a multi-stemmed bush that makes a great hedge/windbreak. These stems can be coppiced and harvested for many uses, including walking sticks and garden stakes.

Hazelnuts.

Hazelnuts are wind-pollinated and need a pollinator to produce. Plant a mix of varieties close together. The leaves and bark of all these trees, and the pellicles and shells of nuts and acorns have anthelmintic properties. They can help to prevent parasites from building up in an animal’s gut. I have never had to worm my pigs.

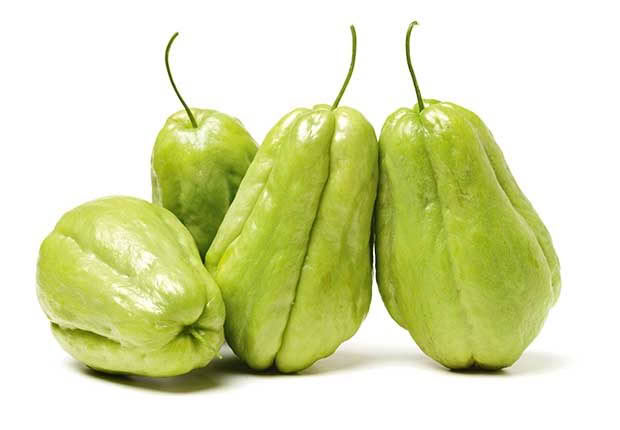

Choko

Choko.

A choko plant is a thing of fairy tales and horror stories. You can sit and watch it grow. I am sure if you fell asleep you would waken entwined in its (edible) tendrils. Anyone who grows a plant will be happy to give you some as they ripen in winter. Plants produce hundreds, possibly thousands, of fruit. My pigs love them. Leave the fruit on your windowsill over winter to sprout. Plant in spring in well-fertilised, moist, loose soil and wait.

The vine will cover any fence, woodpile or tree in the vicinity. It produces its crisp, green vegetable ‘pears’ en masse in autumn. These fruits are edible and I enjoy cooking with them.

Chokos are low in flavour and nutrition, although they do contain high amounts of vitamin C. Their texture is crisp and light. They are quick to sprout in storage. It doesn’t reduce their keeping qualities and pigs will eat the sprout as well. A big advantage is their timing. They ripen later than nuts and acorns, meaning you can pick and store them before the first frost and they’ll stay good into the start of winter.

Fruits

Fruit do not marbleise the fat like nuts and acorns do. They do contain more sugar than the starchy nuts and will be relished by your pigs. The added advantage is they’ll stay on the tree when ripe. You can pick the best for yourself and feed the rejects to the pigs. There is a wide variety of fruit you can plant for your pigs, from early plums at Christmas to Granny Smith apples in May. You can also allow them access to your orchard to eat any fallen fruit. However, be aware that a pig’s weight and size can damage small trees.

My spoilt pigs decline to eat lemons or bucket-loads of citrus skins. They are happy to munch on the occasional orange during winter. I let them eat any fruit, except for too many avocados pips in case they choke on them. I don’t know if it’s a risk or not, but I exercise caution. If you’re planting fruit trees in paddocks, choose large, robust varieties that will look after themselves, not the dwarfing types sold for urban orchards.

The Japanese plum varieties tend to grow bigger than the English varieties and can be grown easily from cuttings. Seedling trees are generally hardier and larger, sending out big root systems to mine nutrients from a large area, and they anchor the tree well. It doesn’t matter if the fruit is above picking height. What you can’t harvest will drop for the pigs.

Pears and apple seedlings are easy to grow but can vary hugely from the mother seed. However, seedling trees will live a lot longer. A graft pear’s lifespan can be as short as 40 years, but seedling pears can live three times as long or more. Seedling-grown peaches, nectarines and apricots produce fruit very similar to the mother fruit. They are also less susceptible to the fungal diseases of brown rot and leaf curl. To get seedling-grown trees you stick a seed in a pot and wait. You may wait a year or two longer for fruit than if you’d bought a grafted tree, but it will be worth it.

Melons

One seed can turn into a whole lot of delicious-to-pigs melons in one season.

A friend warned me the ‘pie melon’ plant she gave me ‘needed a bit of space’ but I didn’t realise she meant 10m² plus the duck pen, the milking shed and the grapefruit tree. All that growth produced almost a ton of melons and the pigs adored them. Chooks, sheep, and cows also got a share. However, it’s probably not a pie melon. The plant I bought bore large, white fruit. It looks quite different to the pictures of the ‘pie melon’ advertised by Kings Seeds (which is Citrullus lanatus, a type of watermelon).

Mine appears to be Cucurbita ficifolia (figleaf gourd or shark’s fin melon), a type of squash. It stores so well it was used as stock food on ships but it’s also a popular human food. The seeds are the most nutritious part and the Mexicans use them to make a version of peanut brittle. The Spanish turn the flesh into jams, sweets, and confectionery. I store mine until late winter when everything else is eaten, then smash them open for the pigs to munch on.

Yacon

Yacon is a root vegetable from South America that has thrived in my forest garden for years. It’s easy to grow, prolific, disease-free, and we all enjoy eating it. The knobbly growing tuber (which looks like pink ginger) grows a soft-leaved, multi-stemmed plant about a metre tall which burns off after the first frost. I leave tubers in the soil all winter (possible thanks to my climate), then harvest bucketfuls of smooth, kumara-like, juicy, crisp tubers which are tasty both for us and the pigs.

Yacon tastes quite sweet but is low in calories. It has a prebiotic effect, helping to feed beneficial bacteria in the gut. Pigs love it. I tend to harvest it in late winter due to its ease of storage in the ground, feeding it out when other stores have been consumed, but it can be eaten from late May. Tubers for growing are usually available on TradeMe or at NZ Tree Crop plant sales.

Grass

Do not underestimate the value of grass in a pig’s diet. Pigs equate to roughly 1.6 stock units; in other words, they will eat as much forage as 1.6 breeding ewes. The heritage breeds require green grass and fibre in their diet, especially when lactating. My black Devon sows make quite obvious requests to come up onto the lawn for extra rations of lush grass when confined to the piglet paddock.

Kunekune should be entirely grass-fed to prevent them getting over-fat, but most other heritage breeds do better with supplementary feeding. The commercial large white is least suited to grazing as its stomach is unable to digest high amounts of fibre and they don’t grow well. For them, grass should be 10% (weaner) to 50% (mature boar) of their diet.

Pigs consume a variety of grasses, clover, and herbs which gives the pork flavour complexity and depth. The constant exercise of foraging improves the texture of the meat. Pigs can damage growing grass. Soft ground tends to get cut up by their sharp hooves in winter. Pigs can and will use their noses to ‘root’, turning the grass over to get at the roots and bugs. A nose ring (or three) in the gristle of their snout will stop this.

Milk

I often get unwanted milk from dairy farmers to feed to my pigs. Milk contains lysine, an essential amino acid that is often added to commercial pig food.

Whole milk can contribute to very fatty pork. I water it down, and never feed it to kunekune pigs. I store in light-proof drums until it turns into curds and whey; it can look quite disgusting, but the pigs relish it. I scoop the cheesey curds off for the chickens. If exposed to light and heat in a clear plastic bulk container over summer, it will go sour and unpalatable after a few months. The pigs will let you know when.

Crops

Pigs without nose rings will do a fantastic job of digging over the ground for new vegetable gardens. If allowed access to root crops, they will self-serve. All vegetables we eat are suitable for pigs, and also turnips and brassicas grown for cow fodder.

Scraps

Pigs consume just about anything, making them fantastic garbage disposal units. Mine only turn up their snouts at eggshells, citrus peel and onion skins. To prevent disease, it is illegal to feed food scraps containing meat to pigs unless you cook (or re-cook) it. Any foods containing meat or that have been in touch with meat (eg, in the rubbish) must be cooked at 100°C for an hour to kill diseases like foot-and-mouth and the swine fevers.

Vegetable scraps are ok to feed raw unless they have touched meat – then they must be cooked. Cooking also makes it easier for a pig to digest the food and gain calories from it.

WHY YOU NEED TO TALK TO YOUR HOME-KILL BUTCHER BEFORE THEY PROCESS YOUR TASTY PIG

If a pig is fat, it can be skinned instead of scalded. I always do this for baconers as I don’t like the rind. If it is skinned, your butcher can separate the excess fat before processing and render it down into tasty, nutritious lard for cooking. I was horrified when the fat from one of my acorn-finished pigs was substituted with commercially-raised fat when my butcher made my salamis. Salami contains about 10 percent fat and it needs to be firm. My butcher prefers to use standardised commercial saturated fat. I now make my own salami using my pig’s fat.

DO NOT FEED THIS TO YOUR PIGS

Never give stale feed to pigs. This is anything contaminated by mould, that has a bad odour, or that is turning odd colours. White clean moulds in moderate amounts are not an issue, but food with black, yellow or green moulds should be discarded. The mycotoxins they produce can cause vomiting, reproductive problems (including abortions) and even death in extreme cases.

RENDERING FAT

Fat is a natural, tasty, highly-nutritious cooking oil (with zero food miles). Pig fat is known as lard and beef fat as tallow, but processing is the same for both. Lard has a smoke point of 185°C, slightly higher than coconut oil and about the same as extra-virgin olive oil. Tallow’s smoke point is 250°C, higher than most cooking oils.

Get your butcher to shave off any excess fat between the skin and muscle (known as the ‘fatback’) and to remove any fat around the kidneys and inside the loin. This visceral fat (called leaf lard overseas) is the highest-grade fat. It has a mild flavour and is often used in cooking, most famously in moist, flaky pastry. There are two methods to rendering fat into useable lard. I use the dry method for fatback because it is easier. I use the wet method for leaf lard as it reduces the flavour and increases the smoke point. The fats can be frozen at any stage.

The dry method

Place fat in a roasting dish in the oven at a low temperature (about 120°C) until it melts. Pour the melted fat into a cheesecloth-lined sieve and let it drip through into a metal bowl.

Once the fat has cooled a bit – but not set – pour it from the metal bowl into an ice-cream container/s and freeze until needed. This process can take several hours. Keep pouring off melted fat until all that remains are dry crispy ‘bits’. Dogs love crunching on these when cool but don’t feed too many at once.

The wet method

Place the chopped fat in a saucepan with some water and simmer until the fat melts. Allow to cool and skim off the fat.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.