How Papamoa couple Gabrielle and Andrew Walton’s long-term vision to grow their home tree by tree was made into reality

A couple, seeing the wood within the trees, set out with a long-term vision for a new home and an alternative forestry industry.

Words: Emma Rawson Photos: Simon Young

TIGER COUNTRY IS what David Blackley called the steep, toothy parts of his Bay of Plenty farm, with its thick jungle of gorse, pampas and woolly nightshade shrubs as tall as pongas.

In the early years of Summerhill, a 400-hectare sheep and beef farm, anyone who braved the hairy parts of the terrain emerged scratched to hell and with stinging calf muscles.

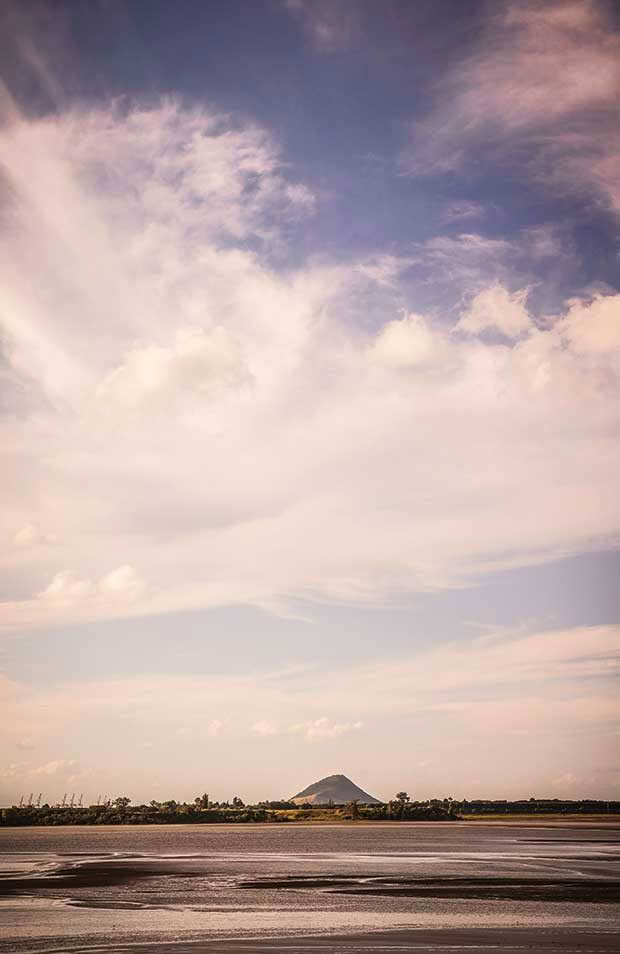

In 1958, David and his wife Cloie bought the property, from which one can peer down on Papamoa and Mt Maunganui. Today, these are among the fastest-growing suburbs in New Zealand, but back then there was just a sprinkle of baches near the beach.

Gabrielle and Andrew Walton’s home in Rangataua Bay took two years to build, but it was decades in the making considering the time it took to grow the timber on their forestry farm, Summer Hill Timbers.

Summerhill’s mineral-deficient farmland, which caused bush sickness in cattle, was transformed into prime pasture with aerial cobalt topdressing in the 1940s. But scrub and erosion remained a problem.

To tame the tiger, David and Cloie initially planted pine on the steepest and most remote slopes.

In 1984, their daughter Gabrielle Walton, fresh out of Lincoln University with a post-graduate diploma in landscape architecture and a head full of ideas, convinced them to diversify into specialty timber species.

Later, Gabrielle and her husband Andrew formed a joint venture with David and Cloie and planted second-rotation pine and more specialty trees.

Summerhill now has more than 100 hectares in mixed species including Cupressus lusitanica (cypress), Acacia melanoxylon (tasmanian blackwood), Eucalyptus regnans (victorian ash) and Eucalyptus saligna (sydney blue gum) — many now coming into maturity — as well as poplar, alder, the fast-growing Chinese native paulownia and the forest behemoth, redwood.

The house is built on the site of a former mandarin and avocado orchard and overlooks Mt Maunganui/Mauao. When the wind is blowing in the right direction, Gabrielle and Andrew can hear concerts playing at ASB Baypark Stadium.

Would there be a market for the timber of these exotics when they were ready to be harvested decades down the track? Gabrielle wasn’t certain but the Blackley/Walton team was determined.

“It was a gamble, but we didn’t want to put all our eggs in one basket and to plant only pine [which forms 90 per cent of the country’s commercial plantings],” Gabrielle says. “I really believed there was a future in specialty timber.

“New Zealand has what I call a ‘pine mentality’. In the search for a quick-growing, easy cash crop, we had forgotten about all these other beautiful, high-value timbers with so much potential.”

The door is made from the same timber but is dark because it was treated with a traditional Japanese charred-timber method called shou sugi ban. The door handle is a mānuka branch.

It took 35 years for “tiger country” to earn its stripes. The first plantations of cypress, victorian ash and eucalyptus are now being selectively harvested, dried and milled and are ready for sale. Gabrielle and Andrew launched their wholesale business Summerhill Timbers in August 2018.

Specialty timber is a lot more work than standard pine, says Gabrielle. Some species grow more slowly and require a lot more pruning. But they fetch a higher price.

“Acacia [tasmanian blackwood] is a pig to grow because it’s a tree that really wants to be a bush with lots of branches. Yet it has rich, dark and extremely hard timber, so it’s worth the effort.”

- A two-bedroom sleep-out was built first while the main house was being constructed. The sleep-out features eucalyptus on the walls.

- A leaf design was cut into ply doors on a CNC (computer numerical control) machine in a similar process to laser cutting.

- The en suite opens straight into the lawn.

- The bedroom, like the en suit, opens to the lawn and pōhutukawas.

- Laser-cut leaves are one of the only trimmings in this simple bedroom.

Many varieties of specialty timber planted in the 1980s, when alternative timbers were being promoted by the government to replace the dwindling native timber supply, are now reaching maturity. As more are used in new builds, demand grows.

“People are becoming more aware of issues such as traceability and a product’s origin. Instead of choosing imported cedar, customers are looking for wood grown in New Zealand. It’s like the garden-to-table movement except it’s more like from forest-to-feature wall.”

Gabrielle and Andrew’s new home in Tauranga’s Rangataua Bay smells of sap and sunshine. The house, built on the site of a former mandarin orchard, is a nine-kilometre drive from Summerhill farm. It is the beautiful articulation of all those decades of hard yakka.

The forest in the Papamoa hills is a 10-minute drive from home.

The house is constructed entirely from timber grown at Summerhill — the only exceptions being redwood sourced from an 80-year-old plantation in the Waikato and some ply behind the redwood cladding for waterproofing.

Gabrielle says growing the timber for a house is akin to the satisfaction a gardener might feel growing vegetables — multiplied by a couple of thousand.

“We measure the trees as they grow every year and it always amazes me how big they get. The felling of a tree is as exciting as growing it.”

The walls of the main house are made from poplar, which has a white-washed Scandinavian look.

There are five different timbers used in the house and sleep-out, including poplar and eucalyptus from a shelterbelt on the internal walls, redwood joinery and exterior cladding and cypress structural beams. Gabrielle selected the timber, scrutinizing it for knots, nicks and discolouration.

Every. Single. Plank. “Every time I saw a knot in the wood, I thought about how we’d pruned the branches of the tree and if we could have done anything differently.”

Andrew was initially worried the contrasting timber colours would look chaotic but loves the result of combining dark blackwood floor, white poplar walls and ceilings, and laminated cypress beams and rafters.

Some moments of the build were nerve-racking for Andrew. Would there be enough of the deep brown tasmanian blackwood to finish the flooring?

“It’s not like you can run into Bunnings and buy extra wood off the shelf. We’d reached the final corner, and it was looking like we were about to run out.”

Gabrielle and Andrew grow much of their food and there are 25 avocado trees growing in the former mandarin orchard.

That explains the streak of sapwood (the outside layer of the timber closer to the bark) running through a plank in the kitchen flooring, a piece Gabrielle had at first rejected.

“I didn’t want to use that piece of timber but the man who did our flooring was a skilled craftsman and worked it in extremely well,” she says. “I’ve grown to like it. The whites of the line emphasize the curve of the tree. It’s now a feature I point out to people.”

The cabinet under the television is in tasmanian blackwood timber with a streak of sapwood.

The Walton’s Tauranga architect John Henderson won a prize in the NZIA Waikato/Bay of Plenty Architecture Awards, and a highly commended in the 2018 NZ Wood Resene Timber Design Awards. The judges praised how New Zealand-grown timber was showcased and heroed in the build.

The first 10 years of a forest plantation are the hardest. Planting the slopes is a feat in itself, then the trees are pruned and thinned. There’s an ongoing battle to keep weeds at bay. “Everything grows well in the Bay of Plenty, including weeds. It’s a huge issue,” says Gabrielle.

Gabrielle loves the illawarra flame tree outside the sleep-out. “It’s funny, I don’t get sentimental about cutting down forestry trees, but I’d be upset if that was ever cut down.”

Over the years, Gabrielle and Andrew’s four children, Rebecca, Hamish, Sam and Tim, all now in their 20s, helped with planting and pruning. “They’ll tell you only too willingly just how many trees they have planted,” says Gabrielle. “The boys even had small businesses selling firewood while they were at school.”

Before they had the Rangataua Bay house, the Waltons lived in Mt Maunganui closer to Andrew’s former accounting practice (he’s since begun working full-time on Summerhill Timber). When holiday-goers flocked to the Mount for the beach, the family headed for the hills.

“We built a cabin as we wanted the kids to grow up appreciating the forest. In Japan, they call the idea of enjoying trees ‘forest bathing’. Often our kids would bring their friends to the forest, and at first they would stick close to the cabin, but eventually, they’d become more confident and go exploring.”

- A cabin near a dam in the forest was built 17 years ago.

- Andrew and Gabrielle liked the timber interiors of the two-bedroom cabin so much they decided to line their main house in timber also.

- The interiors of the cabin.

In the 30-year lifecycle of a plantation forest, Andrew’s favourite stages are when the seedlings are established (and shooting up triumphant over the weeds) and years later when the mature canopy has grown. “At that time, we’ve done all the hard work, and the trees have had their final prune. The trees are big, and you can walk beneath them. It’s a special feeling.”

Intergenerational forestry is popular in parts of Europe. In some villages, one generation plants seedlings for the next generation to harvest decades later. Andrew and Gabrielle say their children are probably daunted by the idea of taking over the forest in the future, “the finances are hard to get your head around when you’re in your 20s. It’s a lot of money up front and a 30-year wait for pay-off,” says Andrew.

But they are jointly applying for grants through the government’s One Billion Trees programme. “We’ll do all the hard work of course, but it’s nice to think of the forest carrying on,” he says.

THE WHEEL DEAL

Gabrielle’s parents Cloie and David gifted 126 hectares of their land to a charitable trust for public use. Summerhill Mountain Bike Park includes five different mountain-biking trails in the forest as well as jumps and obstacles. There is also a walking track that connects to the neighbouring Papamoa Hills Regional Park (Te Rae O Papamoa).

Gabrielle and her father David.

Gabrielle and her parents helped set up the park with the Bay of Plenty Regional Council in 2004. It was the first regional park outside the Auckland and Wellington regions.

“Papamoa and Mt Maunganui have grown so much, and my mother is really passionate about retaining a greenbelt in the city,” says Gabrielle, who also manages the charitable trust.

Views of Tauranga harbour attracted Gabrielle’s father to the land originally.

CAREFUL MANAGEMENT

Summerhill Timber uses “selective harvesting” to maintain continuous-cover forestry when felling the specialty timber trees. Only the biggest trees are taken out, leaving the rest of the forest intact.

Gabrielle and Andrew in front of recently felled 35-year-old cypress and tasmanian blackwood trees.

This method is often considered more sustainable than clear-felling, which sees huge patches of hillside cleared and can lead to erosion and water pollution.

THE WOOD LIFE

Building with specialty timbers can be rewarding, but it has its challenges. Gabrielle says the Building Code sets minimum performance standards for wood, but largely references only radiata pine and douglas fir.

Contract forestry workers Caleb Davies and Rob Brown take a break from the cypress harvest.

In many cases, a build using an unlisted timber requires permission from a local council (called an Alternative Solution). This is to demonstrate the timber will comply with the code and is fit for purpose. Gabrielle and Andrew had to use data sourced from Australia to prove that eucalyptus intended for their framing timber was suitable.

A forest walk under canopy-stage redwood and alder.

Gabrielle is a member of the Farm Forestry Association, encouraging the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) to look at including more specialty timbers in the Building Code. Architects shouldn’t be deterred from designing houses for construction with specialty varieties, she says.

“Attaining the Alternative Solution was straightforward for us in the end. The joiner and builders who worked on our home found the project rewarding. Our joiner fell in love with redwood timber and said he’d sworn off imported cedar for good.”

Other advantages include the natural strength, durability and versatility of woods such as cypress, which is not treated with chromated copper arsenate (CCA) and can be used for structural parts such as beams and rafters.

MORE HERE:

How a small Waikato farm harnesses the power of Paulownia, the fastest-growing tree in the world

Ellis Emmett on conquering mountains, underwater explorations and life in a treehouse

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.