How daylight (and lack of it) impacts a hen’s health and egg production

One of the biggest influences on your hens’ health is a star in the sky.

Words: Sue Clarke & Nadene Hall

Poultry – like all birds – are naturally seasonal creatures. Their bodies respond to increasing and decreasing hours of sunlight (or to artificial light if kept in windowless sheds).

In late July, birds respond to longer days by mating and laying eggs. When daylight hours begin to fall in late December, it’s the signal to wean their chicks, moult their feathers, and prepare for winter. Some bird species do this by flying away to warmer climates. Poultry grow denser layers of insulator feathers and increase their fat levels.

WHY THE SUPER LAYERS ARE SO SUPER

Domestic poultry has been affected by hundreds of years of breeding decisions by humans as we’ve developed birds with higher and higher egg production capabilities.

Poultry selectively bred to lay a high number of eggs (250-300+) in a year – hybrid commercial hens (Hyline, Shaver) and some light heritage breeds – are less affected when daylight hours reduce.

They continue laying long past where most other breeds of poultry stop, especially in their first 12 months of laying (aged 18-70 weeks).

They’re also far less likely to go ‘broody’. This is when a burst of hormones stops the laying process and prepares the hen’s body for incubation of her eggs.

THE NOT-SO-SUPER LAYERS

Breeds selected for meat growth (known as ‘heavy’ breeds) or both meat and egg production (dual-purpose) tend to have a much stronger seasonal instinct to lay a ‘clutch’. This is 20-30 eggs that they’ll then want to incubate. Once they’ve laid a clutch, they often go ‘broody’, sit on their eggs, and stop laying.

If you can prevent them from going broody, they may lay another 20-30 eggs starting in late December-early January. However, many tend to start moulting quite soon after daylight hours begin to shorten (December 22-23).

By March-April, moulting is in full swing. By May, some birds will have a whole new set of feathers. However, they still won’t resume laying until daylight hours start to increase.

LIGHT IT UP

All of these functions in the hen are controlled by light. Light stimulates:

■ the retinas in the eyes;

■ the pineal gland (deep inside the brain, which controls melatonin, which runs a bird’s biological clock);

■ the pituitary gland (at the base of the brain), known as the ‘master’ gland for its effect on the body’s systems and organs.

When there’s enough hours of light in a day, they all combine to turn on the hormones and other functions required for laying to start. In contrast, decreasing hours of daylight in late summer turns them off.

DAY TO NIGHT

Developing a good day-night rhythm is important to the health of all living creatures (including humans).

The amount of daylight in a typical day depends on where you live. In Auckland, during the summer solstice in late December, it’s around 14 hours, 40 minutes; in Invercargill, it’s almost 16 hours.

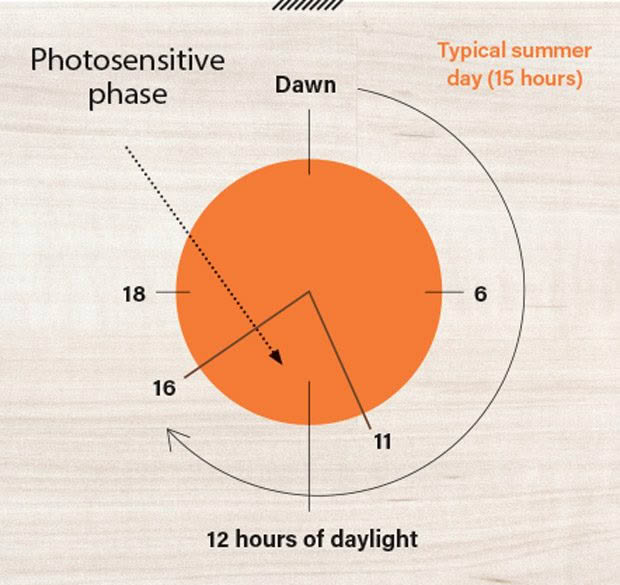

In laying hens, the approach of darkness – known as the photosensitive period – stimulates the release of a yolk from the hen’s ovary. It starts its journey down the oviduct to become the following day’s egg. The photosensitive period begins after the current day’s egg has been laid, until the sun goes down, or the lights go off (15-17 hours of daylight).

Research into intensively housed hens (which receive a carefully controlled amount of light) shows hens maintain egg production for longer when there’s 14 hours of stable daylight (or artificial light).

WHY THE DARK IS GOOD FOR HEALTH & EGG LAYING

The avian body is only triggered to produce melatonin at night. It’s a hormone that regulates the brain’s biological clock, stimulates birds to move around, eat and digest food, and affects respiration, circulation, excretion, reproduction, and the immune system.

Young chicks brooded by their mother understand and adapt to night and day straight away. She protects them, maintains their temperature at night time, and ushers them around to food sources.

If you’re hand-rearing chicks using a light bulb as a heat source – where there’s light 24-7 – it’s vital to slowly establish a day-night routine. This is essential for the on-going development of the chick’s body, including its immune and reproductive systems.

THE BEST WAY TO BROOD CHICKS

If you’re rearing chicks you’ve hatched in an incubator, it’s important to provide a heat source in a brooder for their first few weeks. Many people still use a light bulb or bulbs to warm a brooder.

However, for good health and welfare, we don’t recommend their use. Chicks forced to sit in light 24 hours a day don’t get a day-night routine or the critical hormones they need for good health and growth.

Too bright a light can also overstimulate them and may lead to feather pecking, cannibalism, and death. Another problem comes when you eventually remove the light. The chicks won’t be used to the dark, and they’ll find it very unsettling. They often cheep loudly for a long time, which might lead you to reinstate the light and prolong the problem.

Chicks develop better and faster if you use an infra-red or ceramic heat lamp (above left and at left) or a heat plate (above) that mimics a hen’s body as a heat source in a brooder. These are available from good poultry supply stores, from around $40-$50 for heat lamps and from $125 for a heat plate.

Myth: if lights are on 24-7, a hen will lay more eggs

This is untrue. Light 24-7 is one of the worst things to do to any living creature. A bird living without a ‘night-time’ develops irregular waking and sleeping cycles. It eventually stops eating or laying eggs.

In the commercial world, farmers keep lights on long enough to simulate a typical summer’s day (15-17 hours). They use lights in windowless sheds, or supplement naturally lit sheds (or sheds for birds that free-range) with lights that turn on before dawn and stay on after dusk.

WHAT IF YOUR ONLY OPTION IS A LIGHT BULB?

Chicks need a heat source until they’re 4-5 weeks old. If you’re using an old-fashioned light bulb or bulbs, it’s important to wean chicks off 24-7 light so they can slowly get used to being in the dark.

Start by turning the bulb/s off for an hour each day at a time when it’s still light outside and warm. Increase the time (eventually utilising night-time) until they’re on a regular day-night schedule for the time of year.

Chicks raised under light bulbs will cheep loudly when you first turn off the light. This is almost always a ‘location chirp’, a vocalisation they use in the dark until they find a safe place to sleep or snuggle, after about 10 minutes or so.

Be careful to position drinkers and feeders away from brooder walls. Chicks may smother one another by piling in behind them if they’re frightened by the dark. After a few days, they’ll get used to the dark period and settle more quickly.

SUE’S TIP

If an old-fashioned light bulb is your only option, you can turn it into a DIY heat plate by using a terracotta plant pot as a ‘light shade’.

Put the bulb inside the pot with the socket poking out of the hole. Attach the bulb to its cable/socket. Sit the pot (with the light on) upside down on a large ceramic tile.

This way, there’s no (or very little) light, but the bulb heats the pot and the tile. Be careful with the electrics if you choose to use this option, check the temperature regularly, and always use a surge protector.

MORE HERE

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.