Everything you need to know to make weaning go smoothly

When and how to safely wean young livestock.

Words: Dr Sarah Clews, BVSc

When weaning lambs and calves raised on their mum, there are a few simple rules. Their mums start to encourage them to drink less, and eventually we separate them so they lose all access to the udder.

This happens at an older age than it does for bottle-reared stock and is a natural pattern where things rarely go wrong.

Stock being reared by humans tend to be weaned at a much younger age, making the risks of complications higher.

It’s important to understand the ins and outs of weaning different livestock and the best way to do it.

BEEF CALVES, REARED ON MUM

Calves naturally wean from their mothers at about 10-12 months old, but there are many stories of patient, loving cows still allowing sons bigger than they are to take a swig.

Beef calves on commercial farms are usually weaned by separating them from their mothers when they’re about six months old, or around 220kg (depending on breed). This gives the mother time to regain condition, ready to produce next year’s calf. However, weaning can occur

as early as four months if there’s not enough grass and stock numbers need to be decreased or if mum needs time to regain weight.

Get the timing right

Weaning is very stressful for young stock, so try to make it as easy as possible for them. Choose a time when there is:

• good grass supplies;

• a paddock with good shelter;

• fine weather.

DAIRY CALVES, HAND-REARED

Dairy calves are separated from their mother aged 12-24 hours, so they get a feed or two of her colostrum.

They’re usually raised on calf milk powder and calf meal and weaned while still young. Make the decision based on:

• age, 12 weeks or older;

• weight greater than 100kg;

• eating more than 1kg/day of calf meal each day.

How to do it safely

It’s vital to provide access to a good quality calf meal from when they’re a few days old to encourage development of the rumen (the adults’ stomach chamber).

A pear-shaped abdomen is a sign of a well-developed rumen.

Before weaning, they should also have access to hay (fibre) which helps get their stomachs contracting. However, don’t let them binge on it – have it in a hay net or cage, which encourages them to nibble.

Watch for signs of diarrhoea (often with blood and mucous) during the first week or two following weaning. That’s when they’re most at risk of a disease called coccidiosis, a protozoan parasite they pick up from the outdoor environment, and that can spread in infected faeces. Feeding calf meal that contains a coccidiostat helps to prevent it.

LAMBS, REARED ON MUM

Lambs reared by their mother naturally wean themselves when they’re about six months old.

On commercial farms, lambs are separated from their mothers for weaning at around 3-4 months old. If you’re growing the lambs for meat, you want to aim for them to be 30-34kg at weaning. Avoid weaning under 20kg, as their growth will be markedly slower.

BOTTLE-REARED LAMBS AND GOAT KIDS

If you’ve been bottle-rearing a lamb or goat kid, they’re at high risk of gastric upsets and deathly bloat. For this reason, the recommendation is to wean early, from about 8-12 weeks old.

Vets often see a peak in bloat cases during weaning if the volume of milk is too large or the digestive system isn’t developed enough to deal with a grass diet.

To keep stock as safe as possible, wean by age and rumen development.

Age

Eight weeks is generally considered the minimum. A lamb or kid can survive if it’s weaned as early as six weeks, but you should only consider this if the risk of keeping them on milk is very high, such as ongoing bloat issues.

Rumen development

Weaning from eight weeks means the rumen (the chamber of the stomach that digests grass and supplements other than milk) should be well developed. Offer a meal supplement (known as a ‘creep feed’). It’s designed for lambs and kids to eat from just a few days old and speeds up the development of the rumen.

They should have access to pasture from when they’re a few days old (but also need a warm, dry shelter) and be grazing consistently by the time they’re weaned.

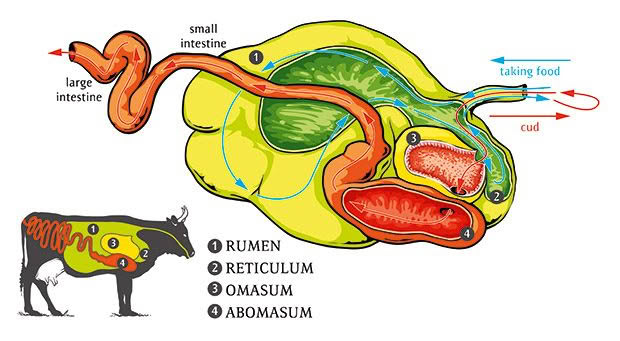

Inside your ruminants

Cows, sheep, and goats have four stomachs. When they’re babies, the abomasum does most of the work. The body senses milk as a calf suckles and diverts it down the esophageal groove to the abomasum, bypassing the rumen. At this stage, the abomasum is twice the size of the rumen and works like the human stomach to digest milk.

By the time a calf is eight weeks old, the abomasum and the rumen are about equal size, as the calf is eating a lot more meal and grass. This helps the rumen to develop a microbial population and grow papillae, the folds which greatly increase its surface area. The more papillae that form, the more nutrients the cow can absorb, and the better their growth rate, milk, and meat production over their lifetime.

By the time they’re 18 months old, a cow’s digestive system is:

• 80% rumen (food storage and fermentation vat);

• 8% abomasum (releases hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes);

• 7% omasum (absorbs water);

• 5% reticulum (removes and digests heavy/dense feed, holds accidentally ingested objects such as nails, bits of wire etc).

THINGS YOU SHOULDN’T DO WHILE WEANING

When you wean, drop the number of feeds and the volume of feeds. Don’t drop a feed in exchange for increasing the volume of others. A mother ewe or doe would let her young drink for shorter periods before kicking them off altogether.

Don’t water down milk – this can cause gut upsets and electrolyte abnormalities.

Never feed water from a bottle, as this can cause water toxicity with severe electrolyte disturbances and anaemia.

WAYS TO PROTECT STOCK HEALTH

Vaccinations

Vaccinate with a broad-spectrum 10-in-1 vaccine, which covers some of the possible causes of abomasal bloat (see page 51). A lamb or kid reared on its mum should be fine with a 5-in-1 or 6-in-1 vaccine.

Probiotics

Add probiotic bacteria to bottles of milk from a young age. Choose a product using a non-gas producing bacteria such as Bifidobacterium animalis.

Beware of using an acidophilus yogurt as a probiotic as it often comes mixed with other bacteria that do produce gas. Simply adding probiotic yoghurt to milk at the time of feeding doesn’t prevent bloat, and may increase the risk, as some of the bacteria in probiotic yoghurt produce gas.

‘Yogurtising’ milk does use acidophilus yogurt to prevent abomasal bloat.

HOW TO PREVENT ABOMASAL BLOAT

One of the big risks when bottle-feeding ruminants is that they can develop the wrong type of stomach bacteria. These can cause the milk to produce large volumes of gas, blowing the stomach up like a balloon.

A sad-looking, non-drinking lamb, calf or kid with a tight, round stomach is an EMERGENCY. Call the vet immediately – don’t wait and see how it goes as they can die from it very quickly (within 30 minutes).

It’s much better to prevent bloat than to treat it – yoghurtising milk, whey milk powder, and small, frequent feeds from birth are all good strategies.

If you’re bottle-feeding, you can yogurtise the milk.

• make up a 4-litre batch of milk as you normally would, according to the milk powder instructions;

• add 200g of unsweetened, acidophilus yogurt (50g per 1-litre milk);

• sit the bucket in the hot water cupboard at 40°C for 24 hours;

• remove half a cup to use as the ‘starter’ for the next day’s batch of milk;

• store the milk in the fridge and feed it cold. Yogurtising removes lactose, the food source for the nasty, gas-producing bacteria. Stock should stay on the yogurtised diet until weaning.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.