Discovering Portugal (again): A food writer hops from sardines to custard tarts in Lisbon, Marvão and Évora

The Alentejo hill town of Marvão.

Exploring in grown-up comfort a country first experienced as a youthful adventurer, our food editor discovers that Portugal still tastes the same.

Words & photos: Anna Tait-Jamieson

Originally published Jan/Feb 2013.

I last visited Portugal 30 years ago. I travelled in a combi van and camped out with friends at the southernmost tip of the Algarve.

It was Easter, everything was closed and all we had with us were wine, olive oil, garlic and a bag of broad beans. We were rescued from starvation by a fisherman at the port who threw us a bag of sardines which we swooped on like a flock of hungry seagulls.

Busking Portuguese style at the Castelo de São Jorge, Lisbon.

We fried them in olive oil and garlic and lived on them for the following two days until a pastelaria opened and we discovered the joys of those little custard tarts called pastéis de nata. Ever since then Portugal has been stored in my memory as the tastes of sardines and custard.

I remembered little else, but on my recent visit to Portugal I was constantly nudged by a feeling of déja vu. The vast rural area of Alentejo, east of Lisbon, brought back memories of a timeless landscape with olive trees, dry-stone walls and the tinkling of bells from invisible sheep.

- The quiet streets of Marvão.

- Marvão’s prison held victims of the Inquisition and its castle walls repelled invaders.

- Joaquina, Marvão’s baker.

- Evora’s Chapel of Bones.

- The mountain town of Castelo de Vide is famous for its mineral water and many fountains.

Nothing much had changed, only this time I wasn’t sleeping in a camper van; I was staying in boutique hotels and travelling with three others in a comfortable car with a black-suited Portuguese driver named Antonio.

Antonio had an inexplicable fear of cows. We discovered this when we asked him to pull over so we could take a closer look at the cork trees that dot the Alentejo landscape. Their bark-stripped trunks appear russet-red against the yellowing pasture, providing a picture-postcard view of Portugal’s prime cork-producing area.

Hand-painted ceramics.

The meadows, or montados, in which they grow also provide grazing for cattle, sheep and pigs. The latter are the black Iberian variety that produce fantastic cured ham, partly because they feed on the acorns from the cork oaks. We wanted to jump the fence but Antonio had seen a group of cattle some distance away and would have none of it.

“Those cows very dangerous,” he warned. He herded us back to the car with the promise we would find much better cork trees elsewhere. In the meantime, he would take us to a lovely town called Marvão.

The steep streets of Castelo de Vide’s medieval Jewish quarter.

Marvão is one of many medieval hill towns in Alentejo built on Roman then Moorish foundations to protect Portugal from invasion. Right up until the Spanish Wars of the 18th century, border towns like Marvão and particularly Elvas, which is now a monument to military construction, were constantly refortified with stronger walls and bigger cannons until they became virtually impregnable.

But as time wore on and the threat of invasion diminished, the garrisons departed and the populations declined until nowadays many of these towns depend heavily on tourism to keep their economies ticking over.

Smoked sausages, air-cured meats and ewe’s milk cheeses are specialities of the Alentejo.

Marvão is like the town time forgot. It exists as a cluster of whitewashed buildings surrounded by a granite wall and overlooked by the remains of a castle. Only 115 people live there and most of them are elderly. Joaquina is a baker who makes rustic loaves in an ancient wood-fired oven. She says she has lived there always, making bread for the villagers who climb the steep steps to her door.

Bread is a big part of the traditional diet in Alentejo. It’s dropped into soups, it’s crumbled and cooked in pork fat with herbs and garlic and it’s even mixed with almonds, sugar and eggs to make a porridgy dessert that is surprisingly good.

I was given the recipe but I suspect it’s one of those dishes that tastes good only in context – in this case, a restaurant in Castelo de Vide, a town famous for both its excellent mineral water and well-preserved Jewish quarter which rambles down the hill from the castle.

The town has embraced its Jewish history, uncovering much that was hidden during the time of the Inquisition when Jews suspected of not seriously renouncing their faith were hanged from stone columns that still stand in some Alentejo towns.

Thin slices of delicious cured tuna, muxama.

The legacy of those times is also found in dishes that enabled Jews to secretly follow their dietary laws. A sausage called alheira, made from poultry flavoured with garlic and herbs to resemble pork, is still eaten today.

Exploring Portuguese cuisine is like eating one’s way through history. The Moors brought rice and oranges and the Portuguese seafarers introduced flavours such as cinnamon, pepper and piri piri chilli. Salt cod, the national dish, also comes from the great Age of Discovery when the Portuguese fished the Grand Banks off Newfoundland.

Pastéis de nata custard tarts.

Reconstituted and often mixed with eggs and potatoes, salt cod is now the basis of hundreds of dishes including my favourite little bacalhau fritters that are served as petiscos before the main course.

The Age of Discovery also brought fabulous wealth. It’s hard to imagine that the recession-ridden country of today once ruled a vast empire, but Portugal’s past is evident in the sumptuous architecture that can be found in the towns of this agricultural region.

Interior of Évora Cathedral.

The best endowed is Évora – the jewel in the crown of Alentejo or, as Antonio would have it, the cherry on the cake. An important town since Roman times, Évora benefited from the largesse of the kings who held court there during the 15th and 16th centuries. It has palaces, churches, monasteries, a glorious cathedral and a university that is jaw-droppingly magnificent.

Nearby is a chapel made from skeletons. It was built by monks, bone by bone, to remind worshippers that death comes to all, regardless of wealth and position – a lesson in humility that was clearly lost on Évora.

Elevador da Bica, one of three funiculars in Lisbon.

While the monks were stacking up bones, the nuns of Évora were baking cakes. I say this because there are so many convent cakes and pastries to be found in this town. The story goes that in medieval times the nuns of Portugal used egg whites to starch their habits and as a result they had enormous quantities of yolks left over. These found their way into hundreds of sweets, puddings and cakes, some with delightful names like “nuns’ bellies”.

In Évora, at a restaurant owned by a charming man called Gonçalo, I was introduced to a baked egg pudding called sericaia. It was flavoured with cinnamon and served with syrupy plums from Elvas and it just about finished me off.

View from Lisbon’s castle of São Jorge with the Basilica da Estrela and the River Tejo beyond.

We ate much too well in Alentejo: huge helpings of pork and fish stews flavoured with fresh coriander and washed down with very good local wines. There was no room in my belly for pastries and, besides, Antonio told me the best pastéis de nata were waiting for me in Lisbon.

All I remembered from my previous visit to Lisbon was the colour yellow. I was heartened to discover I was right about this. Lisbon may be a little faded in parts but it’s definitely yellow. As we drove into the centre I saw that the trams were yellow, many of the buildings were yellow and the sun was casting a peachy-yellow glow over the paved expanse of the Praça do Comércio.

Sardine fillets with sweet potato.

Yellow too was the delicious custard tart I’d been promised at the Antiga Confeitaria de Belém. This café with its many blue-tiled rooms has been a temple of tarts since 1837 and claims to still use the original and very secret recipe from the neighbouring monastery of Jerónimos.

This may or may not be true but I do believe its pastéis de nata are the best in Portugal on account of the amazing textural difference between the toffee-crisp pastry and the silky-light custard. They are so good I ate only one; there is nothing like excess to ruin a good taste memory.

The Praça do Comércio. The black raven is the symbol of Lisbon.

I had less luck with the sardines. Friends had told stories of eating sardines grilled on charcoal braziers in the cobbled streets of Bairro Alto and Alfama. But I wandered the hilly streets of Moorish Alfama late one evening without finding a whiff of sardine. I soon discovered it is a seasonal fish. Antonio hadn’t known this because he doesn’t eat seafood – unusual in this fish-eating nation – but a fisherman at the Lisbon market told me the only way I would get a fresh sardine in October was if it was frozen.

There were plenty of sardines in tins. On the Rua dos Bacalhoeiros there’s an old-fashioned conserveira that sells only canned fish. A woman sits at the back pasting on labels and each tin that’s purchased is wrapped in brown paper and tied with string.

Waiting for shoe-shine customers in the Baixa district.

More tinned sardines can be found at a chic restaurant in Lisbon’s splendid square, Praça do Comércio. The restaurant is appropriately named Can the Can; each dish on the menu includes something that comes from a can and the decor features a contemporary chandelier made from hundreds of sardine cans.

We stayed for lunch. The anchovies were memorable and so was the proprieter who gave us his mission statement in words I just had to write down: “The can is present in everything. It is the starting point and it’s something we use to make everything round. In essence what we’re doing is being very Portuguese.”

I didn’t know what it meant to be Portuguese but I did love the quirky nature of Lisbon. I loved riding the funiculars up impossibly steep streets. I loved going into shops that hadn’t changed in a hundred years and I loved listening to young fado singers crying their hearts out in a lovely old bar that had once been a chapel.

I was charmed by the elderly waiter who ceremoniously tied a bib around my neck while I tucked into a plate of goose-foot barnacles on one of Lisbon’s pedestrian streets. And I thought it extraordinary that I could dine at a splendid Michelin-starred restaurant and the following day lunch on mackerel in a tiny bar stocked with fishing gear and cans of sardines.

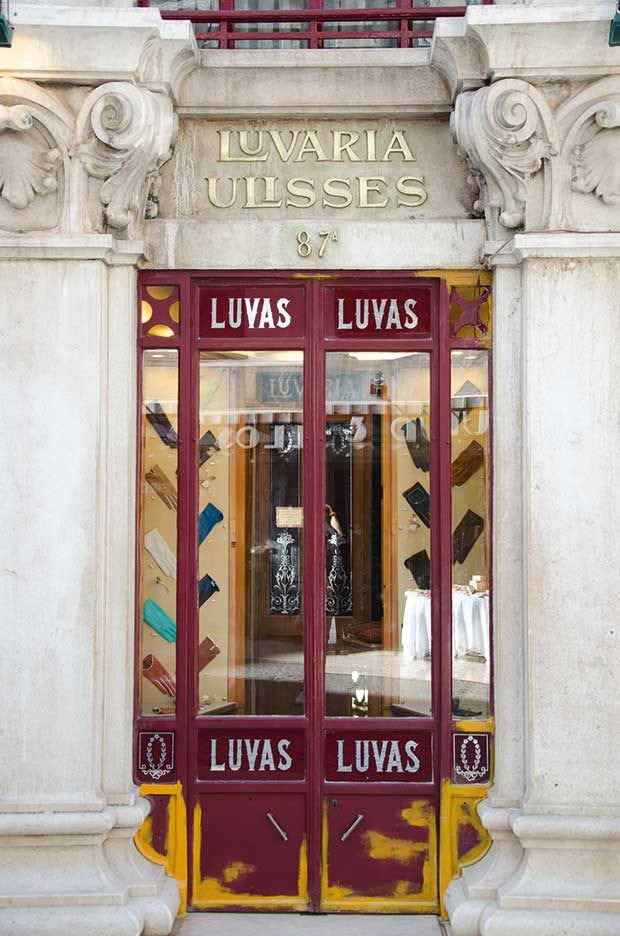

The last little glove shop in Lisbon.

More than anything I was struck by the elegance of a city that’s well past its prime but wearing it well. With that thought in mind, on my last afternoon I wandered through the Baixa in search of a shop I’d been told about: the last little glove shop in Lisbon. Luvaria Ulisses is easy to miss, being so small it can barely take two customers at a time.

I chose a style from the display then the petite woman behind the counter sized up my hands and took a pair of gloves from a box. She used a wooden instrument to stretch each leather finger and a puffer to blow talcum powder inside. With my elbow on a cushion and my fingers stretched out, she worked the glove onto my hand and then asked how it fitted.

Afternoon rush at Belém’s famous pastelaria.

Like a glove, I replied, and the woman smiled as she must have done many times before. And was I happy with the colour? I was. I still am. My gloves are the softest amber-yellow and they will always remind me of Lisbon.

What to do with empty sardine cans.

NOTEBOOK

How to get there: Anna flew to Portugal with Emirates and was hosted by Turismo de Portugal (visitportugal.com) and Turismo de Lisboa.

Where to stay: Albergaria O Poejo, a boutique hotel near Marvao with a restaurant in a converted olive mill. Av. 25 de Abril, Santo António das Areias, a-opoejo.com; Casa do Terreiro do Poço, Several villas and an old winery in the quiet wine town of Borba have been converted into a gorgeous boutique hotel with a wine-tasting cellar and a kitchen that will host cooking classes this summer. Largo dos Combatentes da Grande Guerra n.12, Borba, casadoterreirodopoco.com; Tivoli Lisboa, centrally located five-star hotel. Av. da Liberdade 185, Lisbon, tivolihotels.com

Where to eat: Casa do Parque for enormous helpings of Alentejan cuisine. Av. da Aramenha 37, Castelo de Vide; Mr Pickwick, improbably named but with very good Alentejan cuisine specializing in cataplana dishes. Alcárcova de Cima 3, Évora; Restaurant Eleven, Mediterranean cuisine in a Michelin-starred restaurant, considered by many to be the best in Portugal. Rua Marquês de Fronteira, Jardim Amália Rodrigues, Lisbon; Can the Can, Terreiro do Paço 82/83, Lisbon; Antiga Confeitaria de Belém for the best custard tarts. Also known as Café de Pastéis de Belém. Rua Belém 84, Lisbon; Sol e Pesca was a fishing-supply shop; now it’s a bar that packs in the crowds after midnight. Try thinly sliced dry-cured tuna (muxama) with a glass of vinho verde. Rua Nova do Carvalho 44, Cais do Sodré, Lisbon; Mesa de Frades was an 18th-century chapel, now a cosy fado restaurant and bar; not touristy. Rua dos Remédios 139A, Alfama, Lisbon

What to do: Lisboa Story Centre, a multimedia recreation of Lisbon’s history with an emphasis on the 1755 earthquake that destroyed the city. Located at Terreiro do Paço, otherwise known as the Praça do Comércio.

MORE HERE:

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.