Conservation hero Warwick Wilson turned his Kuaotunu Peninsula bach into Project Kiwi’s home base

One man’s vision for protecting an unspoiled Coromandel Peninsula is shared by family and friends who count themselves lucky to holiday there.

Words: Sue Hoffart Photos: Simon Young

This story was first published in the January/February 2012 issue of NZ Life & Leisure.

During daylight hours, Warwick Wilson’s isolated Coromandel property delivers birdsong at your back and not another soul on the beach. The string of five unsullied bays is a rugged half-hour four-wheel-drive journey from the nearest road, through native bush and pines that sprawl across hundreds of hectares. An endangered dotterel chick totters along the shore. Mussels and oysters lie waiting to be plucked from rocks and tossed on a rusted, home-built 44-gallon-drum barbecue. It’s lovely, alright.

But the real fun begins when night falls on Warwick’s piece of Kuaotunu Peninsula, north of Whitianga. After dark, flaming projectiles soar seaward from a home-made, medieval kind of catapult, built purely for fun from scavenged materials.

North Island brown kiwi eggs are gently plucked from their nests and dispatched to a conservation programme in Rotorua. It’s all starlight and torchlight and solar power out here, with the occasional whirr of a generator or quad-bike headlights sending bunnies scattering into the shadows. Good wine and home-made liquor are quaffed, guitars emerge and tall tales are related around cooking fires.

Warwick’s family and selected friends return to Waitaia Bay year after year, to favourite beaches and camp-sites. Most know each other from earlier summers and their children range freely, picking up friendships and adventures. Latterly, the visiting great-nieces and grandchildren and friends of friends have been buying snazzy Project Kiwi T-shirts – Warwick hosts one of New Zealand’s oldest, most successful kiwi-conservation programmes – and planting pohutukawa trees they raised themselves.

The king of Waitaia Bay is doing his damnedest to protect it all, rejuvenating indigenous bush and abundant kaimoana, the bird-life, the family legacy and the joy of sharing a rare kind of coastal holiday spot.

“Our major aims are to look after what’s precious about this kind of Coromandel,” he says. “It’s some of the best remaining coastal bush we have in the North Island; it’s worth looking after.”

Warwick was smitten the moment he arrived on the beach, scratched and bleeding from a bare-legged scramble along wild-pig tracks, in the spring of 1965. The asking price for the 456-hectare block was uncomfortably high for a Te Kuiti sheep-and-beef farmer with three children at boarding school. He mortgaged himself to the hilt anyway and, within months, wool prices crashed.

The supposed tax write-off became a financial liability he refused to surrender. Instead, he sold the King Country place and found work off the farm, thereby ensuring his relationship with the Waitaia block outlasted a first marriage, a court case with his original business partner and countless meetings with financiers.

Sure, the marriage ended amicably and even the legal battle finished with handshakes and beer but the struggle to keep Waitaia has been long and touch-and-go difficult.

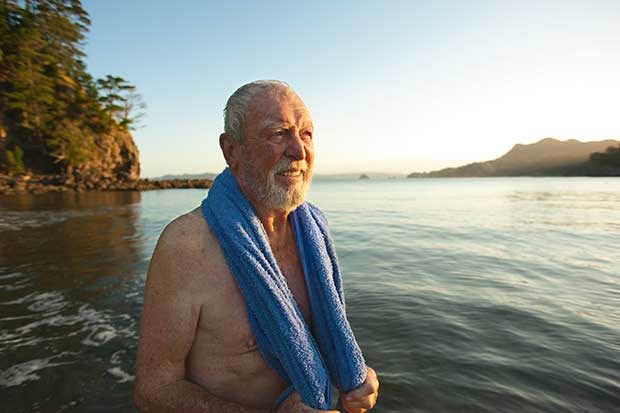

Roger Lampen sets off for a swim at Whauwhau Beach.

In recent times he’s had company for the journey. Warwick and Ann Wilson were married on the beach at Waitaia 13 years ago, ending his second bachelorhood of 19 years. Most of the year Warwick and Ann reside on a 65-hectare lifestyle block with a fine little syrah vineyard and Red Devon stud south of the Bombay Hills at Mangatawhiri. But he’ll take any excuse to be at Waitaia, counting kiwi calls or fixing water pipes or patching up the rough tracks that pass for roads.

Stuart Mitchell, one of the original Whauwhau partners.

In a minor concession to age, the septuagenarian sometimes requires two or three attempts to throw his leg over the quad bike he uses to traverse the property. There is passing mention of two hip replacements. Mostly, he gets on with it.

“There’s no point in slowing down,” he says. “Most guys don’t actually like to lie on their backs and get sunburned; they’re all keen to get on a tractor and cut some scrub or something. It’s all about keeping fit and feeling good and having fun. We do things for fun here, not for grandeur. We’re not trying to impress anybody. I saw enough of that selling real estate in Remuera for seven years.”

Part bird sanctuary, part adventure park, his is the ultimate invitation-only playground for people who want to holiday the way their parents used to. There are no pretensions or power handshakes and not a show-pony beach house in sight. Guests are expected to adhere to a straight-talking list of “reminders” that asks them not to take seafood off the property unless it’s in their bellies, to dig a toilet away from their water source, to keep drugs out.

- Sam Sherrington and Piper Beal-Terenet.

- John Terenet.

- Wright with his sons Martin, Vincent and Adam.

- Stuart’s place at the northern end of Whauwhau Beach.

Feet are bare, fashion forgotten. Everyone makes do, borrows, shares – there is no store nearby. One family rides in on horses each year. The women sport green and silver toenails, courtesy of the New Year’s Day girls’ pedicure session. Everyone contributes to property rates and conservation programmes and they sleep in hammocks and tents, old caravans or an A-frame hut.

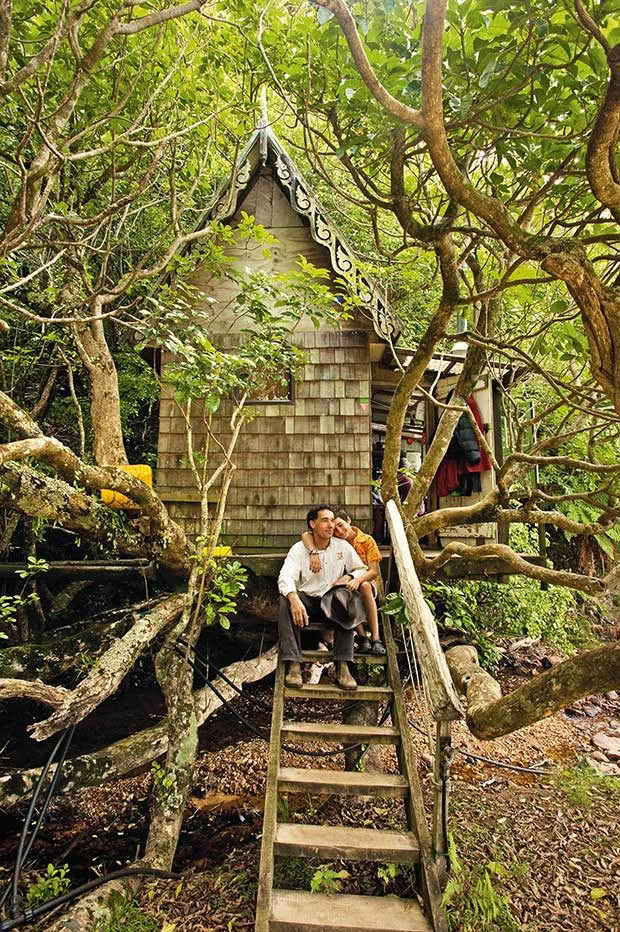

There’s even a tree house among the assorted rustic shacks, each one tucked into the bush and able to be dismantled or moved if some spoilsport, permit-hungry bureaucrat decides to sniff around. Many of these holiday visitors and family members like to pitch in to help control pests, to deal with invasive weeds or improve tracks.

Warwick’s son Andrew was an early proponent and manager of Project Kiwi, while son Nick and friends have instigated a pohutukawa seed-gathering and replanting programme. Both men and their families throw themselves into working bees and conservation projects. Daughter Jenni’s children are trustees of the family trust and everyone’s had a crack at laying traps.

James Wilson (Warwick’s nephew) and his son Max outside The Tree House.

Warwick says the act of sharing the property continually reminds him to value it. His love of the bush is deeply felt. Growing up in the Hunua Ranges south of Auckland, he would race home from school to sit in a miro tree and munch berries alongside kereru. Now watch his face as he pauses to admire an ancient, wind-ravaged puriri or skite about the healthy dotterel population on his property.

“This place shapes you. We’ve grown to appreciate what’s here; we’ve all grown into it,” he says of his family’s increasingly active role as caretakers of the land. “I hardly ever go to Waitaia now without feeling a sense of awe at such a special place.”

OWNERSHIP/SUSTAINABILITY/LOOKING FORWARD

While Warwick owns the lion’s share of his original block outright, two smaller parcels are part-owned by people he admires and a portion is in a family trust. Now that it’s paid off – he cleared that debt about three years ago – he’s working on forming a trust “to protect it from the greed factor in case anybody wants to break it up”. He’d like the property to remain in the hands of extended family who have proved their worth to Waitaia over 40-plus years.

Warwick also owns shares in a neighbouring property, the Whauwhau block, with a group of friends. That purchase came about when a previous shareholder made noises about building a 60-site subdivision. None of the incumbent families would countenance the idea so they all pitched in to buy the man out. Warwick has several ideas for future projects, including tucking a few cabins into the bush and developing a public walkway to encourage ecologically minded visitors. His sentimental green leanings are always balanced by a farmer’s practicality.

“I’m not anti-mining, I’m not anti-1080, I’m not anti anything that’s done properly. One of our biggest supporters for the kiwi project is Waihi Gold Mine. I’m against people who are bigoted or poorly educated, who won’t believe good scientific evidence.”

Rachel Jackson and Hannah Adams at Woodcock Bay – the hammock is made from an old fishing net washed up on the beach.

He is frustrated by anti-1080 protesters, saying the poison is an effective killer of rats and possums and it ensures the survival of native birds and plants. His view, backed up by Forest & Bird, is that it’s impractical and far too expensive to manage pests by trapping alone. When pines went in, in the mid-1970s, he was careful to plant only in areas where the bush had been previously cleared for pasture. The remnant native forest and pockets of regenerating kauri remained untouched. The pines are ready for harvesting and will bring some income for the original investors together with a one-off carbon credit payment. Warwick says carbon trading may provide future income for this land.

Neighbouring landowners, including Department of Conservation (DOC), collaborate on pest control and kiwi-protection programmes. While DOC provided valuable start-up funding for Project Kiwi, along with advice and practical help, these days Warwick’s crew leads the Kuaotunu conservation charge.

“I’m surrounded by DOC land that they freely admit they can’t look after terribly well because they are so short staffed and short of funding. We’re smaller and we’re passionate about what we’re doing. We believe we can do a better job than a big government department like DOC. It’s all about teamwork.”

THE LIGHTHOUSE

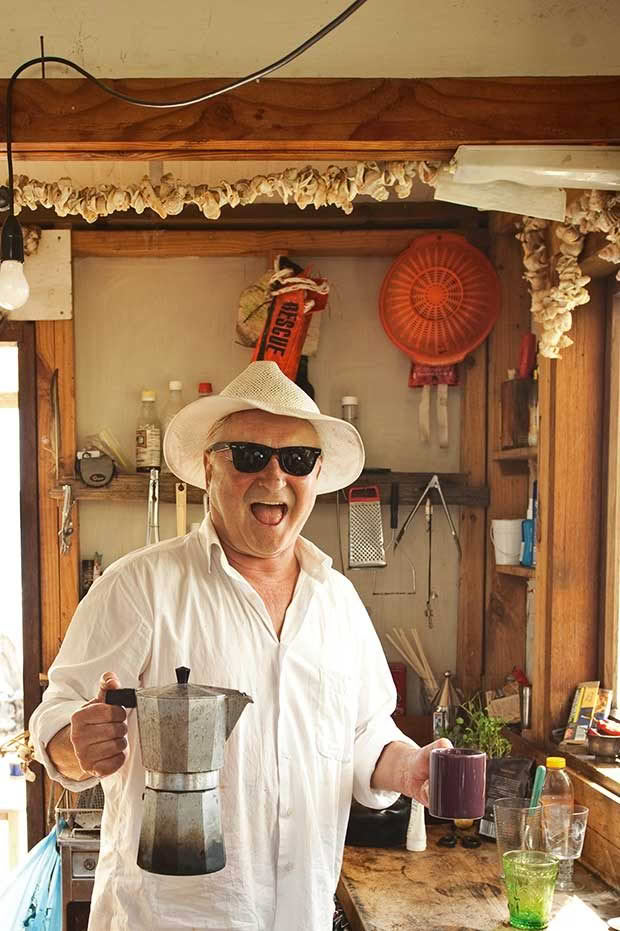

Warwick at The Lighthouse, Whauwhau Beach.

Whenever they need a break from the summertime bustle of Waitaia Bay, Warwick and Ann escape to “The Lighthouse”. This pointy-roofed, green cartoon of a bach above nearby Whauwhau Beach has been cobbled together from bits of unwanted flotsam and material from a dismantled cookhouse. Nothing is wasted around here. “You can’t get Mitre 10 Mega to show up and deliver whatever you need,” Warwick says. “Here, the pride seems to be in having something ingenious. It’s not about having the biggest or the smartest.” He and a mate built the house about 20 years ago, then lassoed it and dragged it along the beach with a bulldozer to its present site.

Visitors are welcome to use anything they find inside the tiny building, including a few cans of Ann’s favourite Ranfurly beer, a gas cooker, a mattress in the loft and a prized flush toilet. Other chattels include a solar radio, candles, 19 mugs and two ceramic wine goblets, gin, a camping toaster, a jar of olives with a rusted lid, Dettol, plenty of fishing tackle and a brown leather jacket. Outside, an old green velour couch sits beneath the corrugated plastic veranda roof and fresh mussels, harvested from the beach below, fit perfectly on Warwick’s home-made barbecue.

CANINE CONTROL

Any dogs which visit Waitaia must undertake formal kiwi-aversion training beforehand, to ensure they don’t attack the protected species. An avian-aversion trainer exposes the dogs to kiwi faeces, frozen kiwi and taxidermied birds. If the canine shows extensive interest, it receives an electric shock.

PROJECT KIWI – THE WILLIAMS FAMILY

By the time Solomon Williams starts school in two years’ time, he will know how to surf, catch fish and reset a trap. He has already learned to name the parts of a kiwi and identify several of its predators. He lives in a borer-ridden 1930s’ cottage that doubles as Project Kiwi headquarters, on the edge of a glorious, pohutukawa-fringed beach. His parents, Jono and Paula, co-manage the 15-year-old conservation initiative that cares for North Island Coromandel brown kiwi. The project fans out from its base on Warwick Wilson’s Waitaia block to embrace DOC land and other neighbouring properties that are home to an estimated 600 kiwi.

Before the Williams took up their post three years ago, they had to tender for the contract and stand their credentials alongside other contenders. But they arrived with well-established, deeply felt ties. Jono met his school-teacher bride here, when she was holidaying at Waitaia with friends. The pair married on the beach, long before they imagined the place might one day offer them work. What’s more, Jono’s mother Ann is married to Warwick and the Wilsons usually stay with the younger couple on their frequent visits. Ann is as fierce an advocate for Project Kiwi as anyone, happily standing on the beach to greet visiting boaties with armloads of fund-raising T-shirts.

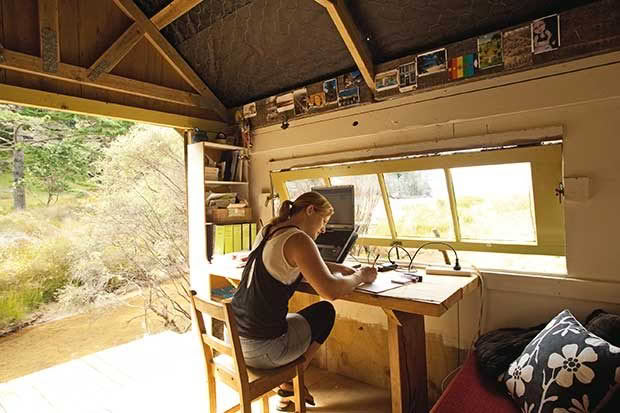

She’s good at it too, Jono says. He’s seen his mother sell $300 worth of shirts to a single group. While Solomon is young Paula stays closer to home, shouldering the fund-raising and administrative roles. She’s the one who coordinates the volunteer workforce which has locals and Waitaia Bay summer holiday-makers pitch in to design, sell or buy T-shirts, to lay bait and check traps or help tag and track kiwi. Up until her scenic stream-side office shed arrived last summer, Paula’s desk stood at the end of their bed and Project Kiwi files were stored in the linen cupboard. She jokes that the priceless pohutukawa-fringed view from her beachfront home is her 52-inch flat-screen television.

Jono looks after the fieldwork, roaming the rugged hill country to trap and poison pests and predators and monitor the resident kiwi population. On the side, he keeps an eye on the dotterel population, helping to ensure breeding success for the endangered shorebirds. Jono is also involved in the operation nest-egg programme that collects kiwi eggs and raises the chicks off site, in captivity, until they are big enough to fend for themselves. The larger birds are released back into the wild where they are better able to ward off predators and have vastly improved survival rates.

“He’s always been mister conservation,” Paula says of her rugby-playing former builder, ex-bouncer, landscape gardener and DOC-worker husband. “When we used to come down here as a couple, the first thing we would do was a beach clean-up, glasses of wine in hand. Jono has always been an environmentalist, a really passionate nature-lover.” He also mans the barbecue for all comers, pouring drinks and cracking jokes while keeping an eye on the wild pork with spice-drenched, slow-cooked potatoes and kumara on the side.

Indoor cooking and lighting rely on gas and solar power. With the track to the main road often impassable in winter, their impressive vegetable garden is a necessity. In summer, Solomon frequently gives up his room to a guest or two and holidaying visitors call on the couple’s bountiful hospitality and good humour. “We see ourselves as caretakers on behalf of the Wilson family,” Paula says. “When people need questions answered or the water’s not working, we assume that responsibility. It’s kind of our payment for living here, having this lifestyle.”

WHO ARE WAITAIANS?

The first time Louise Harness visited Waitaia Bay, she stayed in a little hut built into the arms of a pohutukawa. “I will never forget the way the place made me feel,” she says of that first visit, staying with Warwick’s son Andrew at Shearwater Bay. “I never let it go. I like the fact it’s unchanging. That pohutukawa is about 400 years old and it’s just there.” More than 20 years later, the former assistant film director is mother to two pretty girls, Cilla and Hana. Partner and camera operator Cameron McLean proposed to her and at least one of the children was conceived here. Every Christmas, the family spends three weeks in an A-frame house beside the bay. “We consider our children among the few in the world who could experience nature like this, the way I did as a child. It’s such a privilege to be part of the Waitaia community.”

It’s 18 years since Lloyd and Maria Woodroofe made their legendary journey into Waitaia Bay. A friend who tackled the impossibly rugged four-wheel-drive-only track before them warned: “Don’t come, don’t come, you’ll die”. But the pair persisted, driving a van loaded with their six children and a mastiff dog, towing a caravan full of camping gear. Lloyd laughs about it now, recalling the way he used a chainsaw to prune trees and lay planks beneath the caravan wheels to manoeuvre around every tight bend. It’s a story for the Waitaian annals.

On their arrival, Warwick offered them a temporary resting place for the caravan. The caravan has never left the grassy knoll above Shearwater Beach, so named because the Wilson children once rescued a shearwater bird on the pink-shelled beach below. “It’s unique in that it’s a beautiful, valuable coastal property and the money doesn’t matter,” Lloyd says. “It’s the old New Zealand, where you knew somebody who had a farm with access to the beach. So much beautiful coastal stuff has been taken up by the wealthy. Look at the people who come here.

One or two could choose to holiday where they wanted to but wealthy people aren’t going to poo in a short-drop and make do with camping. Because of Warwick, the average Joe can walk down on the beach, pull snapper in off the beach. New Year’s Day, we were sitting there and there was no one else on it.”

Ann and Warwick share breakfast with their grandchildren Hannah Adams and Solomon Williams at Waitaia Bay.

Lloyd and Maria describe themselves as ex-hippies, makers of kauri furniture, feijoa brandy and coffee liqueur which is offered to guests at 11.00am on a Monday. Lloyd rides superbikes, claims to work as little as possible and observes humanity closely. He likes Warwick Wilson, describing him as a humble man. “He’s real old school,” Lloyd says. “He’s a diamond in the rough. He’s a hard guy… a straight shooter. He’s a very intelligent man. He’s got a real love for people and a real heart for people.”

The youngest Woodroofe is aged 25 now and living in Germany but the family still congregates here each summer. And Lloyd and Maria have long since dismissed the notion of holidaying anywhere else. “Why would you?”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

OTHER STORIES YOU MIGHT LIKE

Photo essay: Discover the historic baches of Rangitoto Island

Chris Giblin and Sarah Mathew call Glenfern wildlife sanctuary on Great Barrier Island home

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.