At home with Northland artist Lester Hall

Lester strikes a pose for this portrait in an ironic nod to the period of the first contact between Māori and Pākehā, which often occupies his thoughts as an artist. It’s not his usual kit.

Lester Hall uses art to make sense of New Zealand’s multi-cultural history — and future.

Words: Kate Coughlan Photos: Jane Ussher

Lester Hall has a great idea, which is hardly news since the Northland-based artist is neither short of ideas nor the ability to articulate them in his work. He wants Aotearoa to initiate an international competition called the World Cup of Colonized Outcomes. Then he wants us to win it.

“We are trying to make this relationship between Māori and Pākehā work, but we don’t take it seriously enough. If there were a world cup for creating the best colonized nation in the world, we would have a plan, and we would find ways to win it. Our politicians would lead us to victory. But they are silent on how we should deal with Treaty of Waitangi reparations. Like a bunch of spoiled brats, we just talk about money.”

Lester’s work, often an eyebrow-raising tongue-in-cheek perspective on the connection/collision of the colonial worlds of Māori and Pākehā, has found its way into the homes and hearts of many New Zealanders. And no one is more surprised by this than the artist himself.

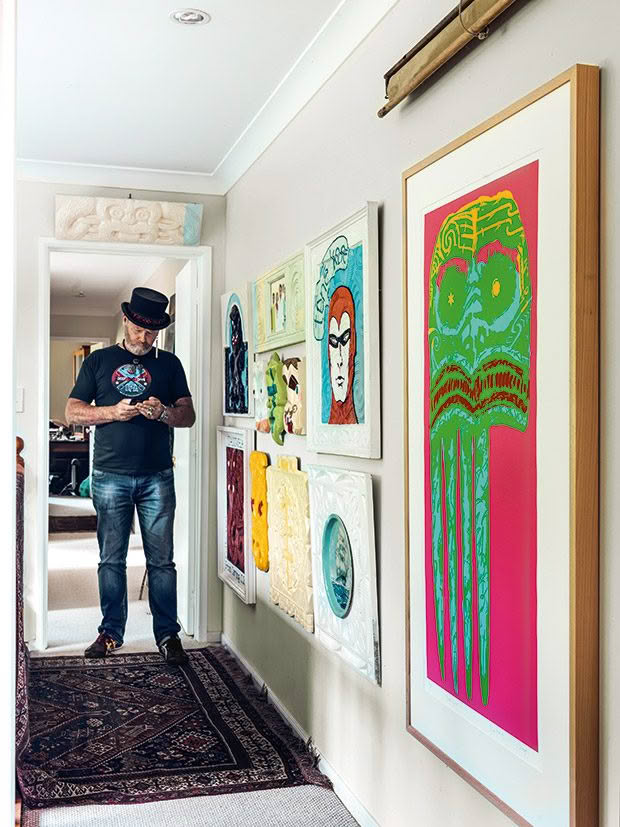

Painted carvings, sculpted reliefs of Māori chiefs and Lester’s Barnet Burns artwork (top) form the nucleus of what the artist refers to as his Wall of Contemplation. Painting and carvings come and go on the wall as he ponders the relationships between them.

“I started the Ngāti Pākehā series 25 years ago when it was still ‘horis and whities’; trying to make sense of stuff within myself. It wasn’t to make money. I had an exhibition thinking I would maybe sell two prints, but I ended up with a business.”

Lester has never planned his life, which is probably a good thing because for the most part, he hasn’t had a high opinion of himself. Without the serendipity of fateful interventions, he’d surely have sold himself short. “I never thought I’d create something good enough for me to respect; that I’d draw anything properly. I expected to fail. That there are some artworks I am proud of is an absolute surprise. I can’t believe it. I am astonished that I make a living from art.”

The universe, however, saw otherwise and from time to time threw Lester a lifeline. The way he sees it, everything good has come along at the hand of fate – his art and health diagnosis being two great examples. Firstly his art.

Artist Paora Tiatoa’s new work, Māori Lynn, to the right of Lester’s Phantom, appropriates Andy Warhol’s work to leverage a conversation about treasures and Māori taonga held in the British Museum. Lester followed the Phantom cartoon strips as a child in the daily Dominion newspaper, and his Phantom Country series shows his love of black line drawing.

Meet Lester in his 20s. He’s left adolescence behind in his hometown of Wellington and moved to Auckland. He’s a boozer (a drunk, to be honest), a casual but skilled labourer, hooning around – sometimes drunkenly – on a 10-speed bike or in a “broken-arse” Fiat 127 with an old-fashioned dial telephone on the dashboard and a pair of Barbie dolls doing high kicks from the windscreen wipers.

(His first car had been a 1960 Cadillac Fleetwood convertible in which there might have been some late-night speed runs along the motorway near Porirua with no exhaust pipes, flames lighting up the underside of the car. But that was another time, right?)

While life doesn’t fit Lester comfortably, it is not entirely black either. Where he sees ugliness, he also sees the potential for visual improvements. He recalls, as a little boy, staring at the dashboard of the family car, wanting to make it look nicer with a thicker piece there, a slimmer one here…

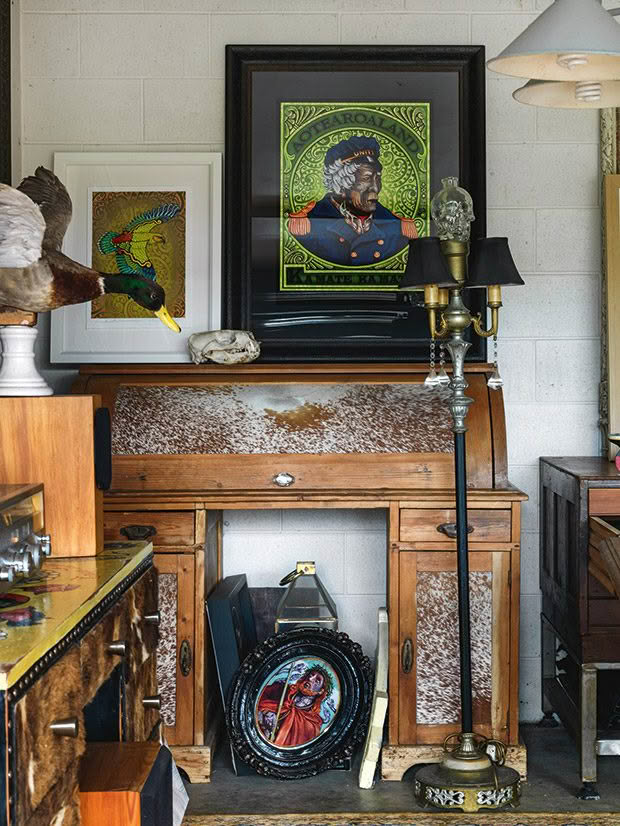

Above the Lester-fied roll-top desk (inlaid with cowhide) is a special version of Lester’s Ka Mate Ka Mate artwork waiting to be packed and sent to the Hori Gallery in Ōtaki. The serial upcycler is using a repurposed Crystal Head Vodka bottle to form a lampshade on a stand that has also been Lester-fied.

Also always with him in that imperfect world are the teachings of the Catholic nuns and priests of his Island Bay childhood. Visions of terrifying demons and the everlasting flames of hell are unwelcome companions.

“Women looking like Batman in their nun’s outfits telling me every day that there are devils everywhere. It is dreadful, as a five-year-old, to be constantly in a cycle of terrifying questioning: Is hell real? Answer: Yes, hell is real. Will the burning hurt forever? Answer: Yes, you will feel the pain forever.”

Lester not only creates his artworks, but also prints them, sends them out for framing and despatches them himself. He has been a self-supporting artist for more than 20 years and is proud of it.

These dark thoughts about sin, punishment and the unlikelihood of redemption quietly grind deep ruts in his neural pathways.

Meanwhile, he applies for a job at the Auckland War Memorial Museum and there, in its dusty corridors, fate steers him towards art. Though he had applied for a maintenance job, he ended up creating displays of artefacts, including some famous pieces such as the Kaitaia Lintel and the display for Kave, an internationally significant Melanesian god. One day, his work involved a pre-colonial korowai/cloak, which he had to help hang.

“It was exquisite, with the elegance of the finest Italian wool suit. I had been taught that the Māori were Stone Age people with Neolithic skills. And in my hands was fabric so soft and had such sophistication that it blew something in my mind. How could this be? Maybe Stone Age isn’t necessarily ignorant; Stone Age isn’t just hitting a shellfish with a rock. If Māori could create this, what else was I wrong about?”

- Queen of the Fern II is one of Lester’s most popular artworks. On the drop-leaf table below are three Lester-fied Royal Doulton pieces, including a Marie Antoinette.

- The korowai/cloak on the stairwell wall was a gift from the mother of fellow artist Paora Tiatoa in gratitude for Lester’s mentorship and delivered with a haka and waiata.

- An odd collection on the hall table includes a carving gifted to him (origin unknown), now wearing a bowler hat and a “shipwrecked” Italian chandelier adrift in front of a Lester-fied porthole, all sitting upon a zebra skin.

- He loves the intricacies of insignia design. For years, he has collected bullion badges, of which a small part is visible, and they help inform his drawings.

Lester says his art is a way of making sense of New Zealand’s multi-cultural history. “I am just a white guy trying to understand. I didn’t go to university and study ‘What it means to be Pākehā in the 21st century.’ I’m just a part of a conversation; take what you like and leave the rest.”

Not everyone responds positively to his work; not that criticism bothers him much. “I’ve had a few threats and accusations that I’m an idiot and a maggot goblin [a derisory term for Pākehā]. But my art has made me friends and opened paths I never imagined it would. It has not bought crazed Pākehā to my door going: ‘Yeah, yeah, white supremacy.’ The opposite, it has brought Māori back into my life.

“A gorgeous local tā moko artist, Paitangi, arrived at my door to sing a waiata she’d written and give me korowai. Out of the blue. That’s dumbfounding, humbling and uniquely Kiwi.

Richie Brownsword and his dog Scouty Scout Pants consider bribery by crayfish an excellent way of encouraging Lester to design labels for Richie’s craft-beer brand, Harpooned Beersies.

“There’s this thing called Third Space.* And we are all in this together, whether we like it or not. But we’re not thanking each other. Yet an enormous number of people are putting themselves out, financially and politically, and often at a personal cost. Māori, in particular, are giving great forgiveness, but we are not ending up together over this.”

Of utmost importance to Lester currently is his mentorship of talented artist Paora Tiatoa, of Ngāpuhi and Ngāti Raukawa iwi, in a role he calls a “brotégé” (think, “bro” and “protégé”). “I am passing on to Paora, like the lifeline thrown to me by my dear friend Craig Taylor, a business whisperer who taught me about “sales solutions” and other keys to avoiding the artist’s poverty trap. The knowledge that art is not enough, that an artist must also develop a business-like attitude to the small things.

- The artist is keen to acknowledge both Māori and Pākehā histories in his decoration of the Duke. Take, for example, his enhancement of the bar’s grand piano. “The Māori people who work in that hotel are proud and appreciative of seeing their history at the hotel, and in their hearts, they know they are in Ipipiri, but every map calls it the Bay of Islands. Things change. This wouldn’t have happened 15 years ago — me being allowed to paint the grand piano like this.”

- For several years, Lester has worked on the interiors of the Duke of Marlborough Hotel in Russell, owned by Anton and Bridget Haagh, Riki Kinnaird and Jayne Shirley.

- The Whaling Wall in the dining room references the early days of the then-whaling port when the hotel, first known as Johnny Johnston’s Grog Shop, was granted the country’s first liquor licence in 1827. Lester loves this work and admires the two couples for the employment (50 jobs) they offer and the care they are taking in the grand building’s refurbishment.

“Turning up to the mundane, like doing your invoicing, this is what I have to share with Paora. For so long, it seemed unobtainable for me to make a living from art, but when the universe threw me that peanut, I jumped and caught it.

“The tough and hurtful question we have to face is that equal rights are not the same as equal opportunity, and so fraternity is incredibly relevant, which is why my relationship with Paora is significant to me. He is becoming financially successful, having enjoyed and followed my advice and contacts.

“I have been a self-supporting artist with no breaks for 20 years, and I am proud of that. He searched me out and asked for help, and that is in itself extraordinary. You might say that we ‘brolaborate’.” Which brings the story back to another lifeline tossed by the hands of fate; the diagnosis of his mental state.

Meet Lester two years ago, a renowned artist, in his 60s and 27 years clean and sober. He’s painting in his Kerikeri studio, fully engaged in his biggest-ever commission (to provide art and décor for the Duke of Marlborough Hotel on the Russell foreshore as part of its multi-million dollar refurbishment). The phone rings, and he takes a call from Mike King asking if Lester would be one of seven artists to decorate scooters on which Mike and his team will travel the country talking to kids about mental health.

Early Russell resident Charlotte Badger was a convict and a pirate and the inspiration behind Lester’s Charlotte series, which initially drew the attention of the Duke’s owners. They asked him to decorate not only the hotel but they then named their Paihia waterfront restaurant after Charlotte Badger. “She was quite a woman and quite a troublemaker,” says Lester.

“I had admired Mike’s direct talk and his kaupapa/agenda, so I was privileged to help. He picked my bike, Pūkana of Hope, as his personal ride. I’d included on it the names of my grandnephew and the mother of a young Māori boy who had been admiring my art. They had both committed suicide in the year before.”

After the public launch of Mike’s I Am Hope tour, Lester found Mike outside loading the scooters onto a trailer by himself. To Lester’s offer of help, Mike said: ‘Everyone wants to be in the photo but not do the māhī (work).’

“It’s a bicultural expression acknowledging two histories in the benign setting of a seaside hotel restaurant,” says Lester, discussing the Duke’s decoration with owners Bridget Haagh and Jayne Shirley.

“I suggested he might want me for a driver or something on the trip. I’d thought it was a month away, but it was the next Saturday. When he quickly accepted, I said, ‘No worries bro’ to Mike, and ‘holy crap’ to myself. A month on the road; luckily I’m an artist with nothing better to do.” In hindsight, he can’t think of anything it would have been better to do.

“Mike is a force of nature; a wild creature firing from the hip, a keen intellect and in a street fight for those kids and adults. He demands fierce energy from himself. I love that. We crisscrossed the country doing three full talks a day, two schools and a community in the evening. Get up at 5.30am, sort bikes, have a team talk and breakfast, ride scooters that max out at 55 kilometres to school and talk, eat, ride bikes to next school, talk, ride bikes to town and talk, dinner and team talk. I was keeping the full-time riders on the road and making sure they were safe.”

Lester designs labels for various craft beers brewed by his Kerikeri mate Richie Brownsword of Harpooned Beersies.

The focus on wellness forced Lester to confront his own lack of mental health. That interfering old universe at it once again. “It was time to settle the unknowns. I booked myself into a $500-an-hour psychiatrist and, funny thing, the psychiatrist was late. ‘Hey dude,’ I told him when he finally appeared, ‘I am not happy that you are late, so you are going to get a crystal-clear view of my personality.’

He said he was sorry, and I replied ‘No, you are not, you only said that because I raised it. I’ve driven four hours to see you, and because you are late, I’ll be 20 minutes late getting to the Harbour Bridge, and this has ruined my window for a decent ride home.’ That’s how I see things.”

The diagnosis? Neuro-atypical on the obsessive-compulsive disorder spectrum with severe post-traumatic stress. This is, curiously, a relief to Lester. “I now know it was me, my OCD personality, driving those ruts in my neural pathways about hell and the nuns. It is good to know this; the brilliance of being released from my hatred of that Catholic upbringing. To understand why I reacted the way I did when my brother and sisters didn’t, to know why I see the world the way I do. Not that I am entirely at ease with myself, there’s still that love-hate relationship.

The artist likes the nautical themes and insignia elements of this work even if he doesn’t take to the brews himself. “Funny that I am designing beer labels as I don’t drink. But it is only me that can’t drink.”

“I don’t always like this world; it can be a shit of a place. Everything here is eating something else. Getting sober helped in the way I view things; I was told to be grateful, to have willingness and acceptance, and then a smile would come more easily. The fact is that sleep, self-care and kindness create a much happier day.

“I think humanity is extraordinary. You see what it can do and marvel at its beauty. We are blessed because we live on a stack of understanding created by science and written language. Imagine if all we had was superstition passed down through generations. Then we will throw some poor prick in a flaming cage, and it is a madhouse. I swing from thinking, ‘It is glorious to it’s not, it’s a shithole, to no, it’s stunningly outrageously gorgeous.’”

THE FLAG DEBATE

Lester was initially excited about a new flag but went into orbit over the lack of intelligent and thoughtful debate.

“It could have been awesome, but it was vacuous. Put a rugby symbol on a flag and call it good enough. My red ensign Aotearoa [above, hanging in his stairwell] was just a thought-starter contribution to the discussion, which should have asked: ‘How do we pull in a disaffected Māori man from the Hokianga and a right-wing businessman from Christchurch and find a space for them both?’”

MORE HERE

How Northland artist Shane Hansen found solace with art, whānau and self-care

Ōpōtiki artist Fiona Kerr Gedson transforms feathers into Nepal-inspired mandalas

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.