A writer dives with dolphins and indulges in the delights of Rangiroa

Finger-nibbling sergeant major fish and other tropical specimens school beneath DéDé Excursions’ Torea te Manu while anchored in the Aquarium Reef in Rangiroa’s lagoon.

Rangiroa offers aquatic delights and a slice of France in the Pacific for those willing to take the plunge.

Words: Emma Rawson Photos: Andrew Long

Perched on the side of the boat, my flippers dangling like a mahi mahi on a fishing line, I’m trying to piece together exactly what is happening. As the Torea te Manu seesaws in the waves and Captain Mana rattles off instructions in French in an alarmingly serious tone, I think: “I really should have paid more attention in Madame Mouquet’s French class.”

Channelling Mme Mouquet’s high school French, I decipher what I can: jambes = legs, bateau = boat, rapide = fast, danger, risque majeur… that doesn’t sound good.

A sandspit stretches into Le Lagon Bleu, a lagoon within a lagoon in Rangiroa.

Thankfully, Pierre, DéDé Excursions’ English-speaking guide, throws me a linguistic life preserver: “We need to all jump off the boat at the same time. Then we must swim away very quickly. This is important; the current is strong. Okay, everybody, get ready. Un, deux, trois. Allez, allez!”

And we’re off! The water is a tangle of flippers and limbs. Bobbing next to Pierre, I take a moment to get my bearings.

Blacktip sharks roam the shallow waters of the lagoons — thankfully, they are disinterested in humans. The large lemon sharks on the outskirts of the main lagoon, however, are a little more human-curious.

We’re snorkelling in the Tiputa Pass in Rangiroa, French Polynesia, a world-class marine sanctuary. The enormous atoll in the Tuamotu Archipelago is the third largest in the world, made up of 214 islets and motus (islands), encircling a lagoon so big you can fit the whole island of Tahiti (French Polynesia’s main island) within it. From the window of our plane yesterday, Rangiroa resembled a pearl necklace; the Tiputa Pass, one of only two deep water “openings” in the string of islets. This trench of water acts like an artery from the Pacific Ocean to the lagoon within, and in these unique conditions, fish and other aquatic life thrive.

Today, we hope to spot some.

While other fish scrap for food on the reef, the yellow and black saddled butterflyfish flutters by unfazed.

Head downturned to the ocean floor, the deep water is a clear and vibrant shade of Yves Klein blue. French nouveau realist Klein once described the allure of his signature shade as this: “Blue is the invisible becoming visible. Blue has no dimensions; it is beyond the dimensions of which other colours partake.” I’m starting to think he was onto something. Being submerged in the cobalt water is almost meditative, making wildlife spotting even more extraordinary. My partner Andrew and I spy a tiger shark, an eagle ray and a giant humphead wrasse (aka napoleon fish). A scuba diver beneath us lets off a white safety balloon to warn boats above of their whereabouts. The balloon pirouettes its way to the surface with a hypnotic train of bubbles in tow.

Most day trips to Les Sables Roses or Le Lagon Bleu end in a trip to the Tiputa Pass for sunset dolphin watching — but be quick if trying to capture a photo, the dolphins are fast.

Pierre’s call pulls me from my blue daze: “Quickly, quickly back on the boat.” Hoots and woots alert us to why there was a need for speed as two dolphins are playing in the water on the other side of the Pass. The boat zips us across, and with a splash, we’re in the water again, and the shining silver face of a dolphin is just 30 centimetres away.

The local Tuamotu people say dolphins or te mau ouà (the jumping animals) descend from a group of children who played in the water for so long they turned into marine mammals. The dolphins’ antics today are certainly childlike as they dive, twirl and jump in front of us. Then, as speedily as they arrived, they’re off, gliding away with the current, kids chasing their next big thrill.

Common bottlenose dolphins, two of a pod of approximately 20, greet snorkellers in the deep waters of the Tiputa Pass.

Back on board, the universal word for “I have just stared into the eyes of a dolphin” is “squee”. Euphoric, we gush in our different languages about the experiences. A wide-eyed French woman talks of la joie (joy), an American talks of bucket lists, and an English-speaking Russian excitedly tells us her friend manifested the dolphins in a dream. Everyone nods as though this is plausible — the experience has made us believe in magic. We plunge overboard again, this time at Motu Nui Nui Reef in the lagoon, also known as The Aquarium due to its teeming tropical fish, and the spell continues.

DéDé Excursions’ guide Pierre was born in Rangiroa and can spot a wild creature from a way away. Stick with him in the water for a better chance of seeing the best wildlife.

In the evening, sitting at the big communal table at our accommodation Le Coconut Lodge, we chat with several scuba divers about our adventures, exchanging photos of the aquatic life we’ve seen like they are Pokėmon cards. Le Coconut Lodge is one of several pensions (family guest houses) in Rangiroa serving up French home cooking, friendly chat and excellent recommendations from the manager, Audrey.

Although she hails from the Loire region in France, Audrey has lived in Rangiroa for 19 years and has beautiful tatatau (tattoos) on her arms to show for it. In her career, she’s managed big hotels in Bora Bora, but Rangiroa’s sea life and simplicity captured her heart. “Rangiroa is very different to Tahiti. It’s slower here; not every tourist makes it this far away. It’s a bit special.”

When on dry land, cycling is the easiest and cheapest form of transport, and most pensions provide free bikes for guests.

French Polynesia is a French overseas collectivity, with Paris still controlling many aspects of life. There have been several pushes for independence over the years and calls for compensation for the nuclear tests that took place until 1996 on Mururoa and Fangataufa atolls in the far corners of the region. But despite the chequered history, the Frenchness endures. In Rangiroa, it’s not uncommon to see locals laden with baguettes riding through the flat as crêpe streets on bikes, and coconuts and figs growing wild. Restaurant menus reflect the French immigrants’ and European tourists’ unwillingness to compromise on “essentials” such as imported pâté, cheese and ham.

Kaimana Excursions’ boat anchors in comparatively deeper waters as travellers wade through the shallows to a nearby motu at Le Lagon Bleu.

Vin de Tahiti is perhaps the most obvious attempt to shape these wild isles into a tropical France. Protected from the sea by coconut trees on a motu near Rangiroa’s main village of Avatoru, it is probably the world’s only coral atoll vineyard, the mad dream of French businessman and wine enthusiast Dominique Auroy, who first began trialling growing grapes on the coral-rich soil in the 1990s.

Les Sables Roses — with climate change and rising sea levels, it may be the last chance to see this low-lying sandspit.

Carignan, italia and muscat grapes are some of the most successful varieties in the 2.8-hectare vineyard, which produces about 40,000 bottles of wine from the biannual grape harvest. In the cellar, sampling a white blend called Blanc de Corail, I can taste the passion and true grit (literally) that goes into each glass — the wines have unique mineral characteristics thanks to the lime-rich coral soil. My favourite is the Rosé Nacarat, which has a smoky quality.

Frangipani grow as big as oaks in the sunshine.

The next day, we’re off to see a rose of another kind — Les Sables Roses (Pink Sand Beach). To reach it, we take an hour-and-a-half-long boat ride to Vaiuru on the southeastern corner of the atoll. Wooden huts on stilts perched above the lagoon are used for fish trapping and pearl farming and are some of the only signs of human life we see from the boat. We arrive at Les Sables Roses when the tide is in, leaving just a slither of the pink sandbar contrasted against the turquoise of the lagoon.

The pink colour comes from shells of tiny organisms called foraminifera crushed over the aeons, but unlike them, our time here is brief. We are on to the motu of Teu, where our guide Tatiana introduces us to her relatives Laetitia and Charles. This couple lives on the island alone, harvesting copra to turn into coconut oil in Tahiti. Over a lunch of poisson cru (a family recipe) plus coconut bread and chicken cooked over an open fire, Tatiana tells us Laetitia and Charles have chosen to move here to live a more traditional life. “It’s a hard life, but it’s simple and beautiful. This is a special part of the lagoon,” she says.

Farmers of black pearls at Gauguin’s Pearl carefully remove oysters from their nets; a pocket of flesh is cut open to reveal the jewel inside and, in doing so, the oyster’s life is sacrificed for our demonstration. To keep the oyster alive, technicians must remove the pearl through a tiny opening.

Along with copra, black pearls are a primary income source for Rangiroa locals and those living in the outer Tuamotu Islands. Large top-grade pearls fetch a high price at Gauguin’s Pearl, a pearl farm and academy. Host Vaiana explains why:

A pearl is cultivated when an oyster is introduced to a nucleus resembling a small bead, with the mollusc gradually developing a radiant outer shell around it over several years. If the nucleus is positioned inaccurately, the resulting pearl may be irregular, making it less valuable. The pass rate on the pearl technician’s exam is 80 per cent, and technicians must wait two years to find out if they have passed. It is a fail if two of the 10 oysters spit out their nuclei due to incorrect placement. I buy a wonky C-grade pearl from the shop out of compassion (and due to budgetary constraints).

The Bleu Lagon from above, with the rest of the enormous atoll of Rangiroa stretching into the distance. Photo supplied by Michael Runkel/Tourism Tahiti.

Our final day is at Le Lagon Bleu, a lagoon within the lagoon. The clear waters are teaming with black tip sharks, some as large as 1.5 metres, and the shallows are a nursery of baby sharks. I’m thankful they couldn’t be less interested in us as they patrol the lagoon for fish, and even more appreciative that only one person on our trip sings the Baby Shark song. At the end of our boat ride home, we enter the Tiputa Pass for more dolphin spotting, this time from above the water. At sunset, the dolphins in the Pass start their daily spectacle, jumping in the waves of the changing tide. We watch them flip and coo like youngsters watching a fireworks display. Who needs mortgages, work and adult life when you can be a dolphin — or watch one, at least?

NOTEBOOK

Getting there: Air New Zealand and Air Tahiti Nui fly regularly to French Polynesia’s capital, Papeete, on the island of Tahiti. There is a daily one-hour flight from Papeete to Rangiroa on domestic carrier Air Tahiti.

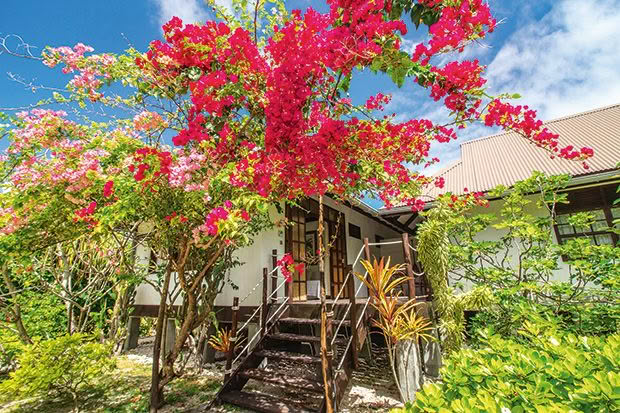

Where to stay: There are only two hotels in Rangiroa, but for a true taste of the Tuamotus, consider staying in one of the local pensions (guest houses). Le Coconut Lodge has a private coral beach and free bicycles to tour the island. All the accommodation in Rangiroa is booked months in advance.

- Beachside pension Le Coconut Lodge has friendly staff, comfy bungalows with four poster beds and trailing bougainvillea.

- Arthur at Vin de Tahiti explains how the grapes are transported by boat to the Avatoru cellar.

- Corrine and Jean-Robert from Les Relais de Joséphine.

Where to eat: Les Relais de Joséphine, a pension and restaurant, is great for a glass of wine while watching dolphins at sunset. On the menu, take your pick from swordfish sushi, crumbed sturgeon, courgette gratin and chocolate torte for dessert, served by Corrine and Jean-Robert, who hail from Paris. The Kia Ora Hotel offers French cuisine with a local twist, such as tahitian prawns with parsley butter and homemade local honey ice cream, served with a glass of wine from Vin de Tahiti.

What to do: Dédé Excursions specialises in snorkelling the Tiputa Pass — repeat trips increase your odds of spotting aquatic life. Marine animals in the Pass vary depending on the time of day and season — at certain times, hammerhead sharks, turtles and manta rays visit. Visiting the Le Lagon Bleu is another must. Kaimana Excursions has set up a hut on one of the deserted motu — your home for the day. Take your reef shoes, the coral is sharp. For a quiet day, visit Les Sables Roses with Orava Excursions. And learn pearls of wisdom at Gauguin’s Pearl.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.