A guide to the seven layers of a successful food forest

Creating a thriving food forest is an art and a science.

Words & photos: Sheryn Dean Additional photos: Guy Frederick & Tessa Chrisp

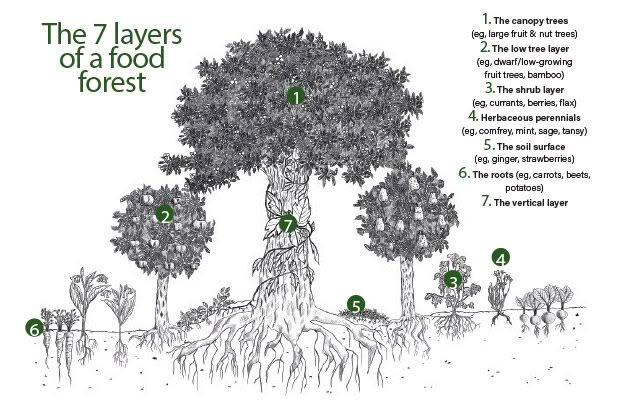

Food forests are a dream garden for many people wanting to become more self-sufficient. But creating the seven layers of trees, shrubs, herbs, root crops, and vines is tricky because the best plants for your block will be dependent on your micro-climate, soil, and the foods you want to produce.

The basic idea is it’s a layered, diverse collection of self-sustaining edible plants grown in a forest-like situation with low inputs and minimal maintenance. I selected the relevant suitable-for-organics trees, plants, and seeds.

I dedicated a north-facing slope of my South Waikato block to it, but after a few years, I was disillusioned and disappointed. I imagined a forest like New Zealand native bush, a dense entwinement of canopy trees, vines, and shrubs.

However, most of the foods I like to eat don’t grow in that environment (eg, peaches, oranges, lettuce, tomatoes, potatoes), and need a lot more space, fresh air, and sunshine.

There are successful food forests in NZ, from the sub-tropical Far North to the windy, most southern coastline of the South Island. They all look very different, like Rory Harding’s inner-city food forest, and Robert and Robyn Guyton’s near Invercargill.

Here’s what I’ve learned from creating a food forest (and what not to do), getting the foundations right is crucial to the success of your forest.

The foundations of a good food forest

1. THE CANOPY TREES

Last month I looked at the food forest’s largest trees. Canopy trees – if you have room for them – should be a mix of:

• productive, eg English walnuts, chestnuts;

• shelter, eg feijoa, Japanese plums, hazelnuts, macadamia, mixed hedgerow;

• nitrogen-fixing, eg alders, locusts, wattle.

Beware of too much shade, too much shelter, creating humid conditions and trees that are too big for the space.

2. THE LOW TREE LAYER

This is where most of the common fruit trees grow, such as apples, pears, peaches, nectarines, plums, apricots, figs, feijoas, citrus, and cherries.

However, it depends on the size of your food forest. In very small gardens, these trees may be the canopy, as they are in Rory Harding’s orchard, especially if they’re on standard-sized rootstocks.

I’ve found leaving a tree unpruned, to grow to its full natural size, means it produces a large quantity of fruit, more than enough for me (and the birds). However, Rory prunes his trees to be quite short and still harvests enormous amounts.

Fill the space between young trees with annual vegetable crops such as pumpkins and melons or try wildflowers. These will die out as the trees grow, but some seeds (eg, fennel) will perpetuate. These wildflowers were among a circle of stone fruit (note the nectarine, bottom left), which grew to touch each other in a few short years.

Nut trees are another option, such as macadamias and hazelnuts, which grow in a wide range of climates and don’t need a lot of maintenance. I don’t recommend almonds and pine nuts; they aren’t reliable producers and it’s time-consuming to process the nuts into something edible.

Mostly, this layer is temperate forest trees that need direct sunlight and space to flourish. I found low canopy trees on standard rootstock are best planted at 6m spacings, which seems huge when the trees are young. However, in a food forest, the idea is to keep everything as low-maintenance as possible, and this wide spacing means less need to prune.

Sheryn’s tips: Don’t plant in rows – follow the lay of the land, such as crests or dells. Plant in horseshoe-shaped sun traps or groups that are easy to mow around.

Create wide paths, so it’s easy to mow them, bring in a trailer of mulch, and cart out your harvest — paths also allow in more light, and provide root space.

If your block is frost-free or you have an area with a frost-free micro-climate, sub-tropicals such as bananas and cherimoya can be planted close together to emulate a jungle.

3. THE SHRUB LAYER

Shrubby plants can tolerate more shade as their natural habitat is dappled woodland. However, temperate types need space and some sunlight, so don’t plant too densely if you want healthy, productive plants.

Raspberries (foreground) are grown between permanent hoops so I can drape netting over them for protection from birds.

Good options include raspberries, blackberries, gooseberries, blueberries, Ugni molinae (also known as NZ cranberry and Chilean guava), elder, and currants. Most of these will multiply quite quickly. They’re all attractive to birds, so give the plants room to spread, and you’ll harvest enough fruit for you and them.

4. THE HERB LAYER

This layer is continuously changing in a forest. Many of these plants are annuals and need full sun, so grow them on the northern side of taller plants.

You’ll find the ones best aligned to your conditions will self-seed and spread without help or come and go with the seasons. At the start, provide good soil, constant moisture, and lots of mulch. This keeps weeds at bay as the herb layer establishes.

This was my garden for root vegetables, but it evolved into an asparagus patch (under the net) and herbal ley when I realised the constant digging was detrimental to the pear and nashi tree roots. A fig tree especially didn’t like its root zone being dug over for weeds in summer. Most tree roots are in the top 30cm of soil, but figs and citrus are especially shallow-rooted.

Once they’re away, let nature take its course. You’ll always find new plants you want to try. You’ll eliminate others when you find that no matter how hungry you get, you’re never going to eat cardoons, and you’d rather they didn’t cross-pollinate with your artichokes (learn from my mistakes).

For maintenance and aesthetic reasons, I contained my herbal layer into defined areas. I had open spaces of nitrogen fixing ground cover (clovers), which I occasionally mowed. This meant I could expand beds (or create new ones).

Plants that worked for me:

• Artichokes – great architectural plants that fill up a lot of space and self-seed.

• Asparagus, rhubarb – need full sun and lots of food, but low maintenance.

• Borage – great flowers for the bees.

• Comfrey – bee food, good compost.

• Cape gooseberries – self-seeding, no maintenance except picking (my type of fruit).

• Day lillies – the red ones tasted best.

• Myoga ginger – no maintenance except to mulch up in winter for the spring shoots.

• Parsley – popped up by itself in the citrus mulch and self-seeded everywhere.

• Perpetual spinach – self-seeding, has regrown every season for over a decade.

• Sorrel – I love the zesty fresh taste (add it to salads and soups), and so do my guinea fowl, so while it’s easy to grow, the guinea fowl eat it long before I do.

Sheryn’s tips: Wildflowers are only viable for a season or two without a lot of maintenance – the flower bank in this layer became a perennial patch with artichokes and arrowroot.

It is also important to plant a wide range of plants and varieties of each plant to find what best suits your microclimate.

5. THE SOIL SURFACE

No forest has bare soil; that’s like sleeping without a blanket. Ground covers provide a thermal layer for roots, encourage symbiotic mycorrhizas, and create habitat for beneficial insects and bugs.

One of my favourite ground covers is clover (red, white, subterranean). They fix nitrogen, are low-growing (so don’t steal sunlight from anything else), feed bees in summer, and can be mown.

Others that worked for me:

Alpine strawberries – these flourished in my forest, although they do take time to get established. Some weeding is worth it for the dainty little fruits you get in return.

Nasturtiums – very pretty, and tasty leaves, flowers, and seeds (which can be pickled and used as a substitute for capers).

The alpine strawberry is one of the parents of the modern strawberry varieties. They fruit all summer long, one or two a day of smaller (and I think tastier) fruit.

Pumpkins and melons were good in summer – I planted them directly into compost piles for a rampant spread. I tried planting orange berry (Rubus pentalobus) several times in different places without success and have never seen it fruiting (other than in photographs).

Expert gardener Abbie Jury found it infested her garden, and only produced two berries. She sentenced it to death over 10 years ago, spraying it out as its roots were too difficult to dig out (Source: jury.co.nz).

Sheryn’s tips: Don’t leave any bare soil. Even grass going to seed is providing protection, habitat, and mulch. It’s also easy to control with a weedeater or mower when you eventually want to plant something else.

6. THE ROOTS

I started with all my root crops growing in the food forest but found I damaged tree roots too much when digging them out. I gradually moved my annual crops of potatoes, garlic, kumara, and yams to a dedicated vegetable garden.

In the loose, good quality soil of the ex-potato patch, the yacon produces bucketfuls of tubers per plant annually. I leave these in the ground over winter as they store a lot better than in a cupboard – I just harvest as needed. Yacon is crunchy, sweet, and a good filler in stirfries.

I leave Jerusalem artichokes, Maori potatoes, and yacon in the ground over winter and dig out what I need by the forkful as required.

7. THE VERTICAL LAYER

Climbers need something to support them. In a real forest, this is usually another tree. Only well-established trees can support their weight and cope with their competitive roots.

I found it’s more work, but more sensible, to grow vines on sheds, along fences, and over dedicated archways. A selection of grapes is essential for me. Trusty old Albany Surprise was my star performer.

Chokos completely covering the ugly stack of firewood (at the back). Bananas, tamarillos, strawberries, and cape gooseberries flourish in front. While it looks lush and happy, I had to dig the clay soil out with a digger and backfill with truckloads of compost, sand, and vermicast before planting.

Chokos flourished once I got them going in good-quality, fertile soil, providing barrow loads of fruit for the pigs. I struggled with kiwifruit as I was missing suitable pollinators and adequate structures to hold them. Melons and pumpkins will grow upwards like a vine if they get support but can be too heavy for smaller trees.

MORE HERE

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.