How mushrooms can transform the soil in your garden

Psilocybe subaeruginosa, decomposer.

A world of fungi is transforming the soil in this self-sufficient garden.

Words & images: Rebecca Stewart

Who: Rebecca, David, Genny, and Summer Stewart

What: 6ha (14.8 acres)

Where: National Park, 1 hour south-west of Taumarunui

Web: ‘Fodder Farm’ and ‘Homesteading New Zealand’ / @fodderfarmnz

When we moved to our block in mid-2020, we found sticky, boggy soil that struggled to cope with the region’s regular winter – often torrential – rain.

The whole terrain needed reconfiguring. Most of the runoff from the house paddock flowed straight into the vegetable garden area and had no way to flow out again.

The rest of the property was pasture with a scattering of lovely large trees, many of which needed pruning, and a few hectares of pine trees. Where some people might see a lot of work, we saw a valuable mulch resource that could benefit our growing areas.

Swales diverting water around the vegetable beds and into other parts of the garden.

To improve the soil, we:

• reshaped the vegetable gardens, using swales to guide the water flow away;

• dug out paths and added the soil to growing beds to raise them;

• filled in the paths with mulched woodchips from tree prunings to a depth of 100-200mm.

We also placed generous amounts of mulch around all the larger perennials, shrubs, and fruit trees to help prevent moisture loss.

THE BIG BONUS

King stropharia (Stropharia rugosa-annulata), decomposer

Wood mulch in and around your garden has another benefit: it creates a fungal-dominated soil. We saw this firsthand as our new garden started to respond to our work, and the wood mulch began to sprout.

We’re experimenting with Korean Natural Farming methods (KNF), collecting indigenous microorganisms from old trees growing around us. We use it to make fungal brews which we add to the soil and compost.

As any mushroom hunter knows, the fungi bug is addictive. We’ve spread fungal brews all over the garden. While we searched the wider landscape for more, a vast fungal network expanded beneath us.

Most people think fungi are the fruiting bodies (mushrooms) you see above ground. But the main body, called mycelium, spreads throughout the soil as a network of fibre-like growth called hyphae. These networks are very effective at extracting nutrients and water from the soil and mulch, making it more available to the surrounding plants.

Beneficial fungi are great little workers within the natural environment, creating healthy soil biology. They also offer direct protection to plants by producing anti-pathogens and out-competing disease organisms.

The two main beneficial fungi for gardens are mycorrhizal and saprophytic.

Mycorrhizal

Fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), mycorrhizal.

These form relationships with plants. They either attach themselves to the plant’s roots (ectomycorrhiza) or penetrate the root’s cell structure (endomycorrhiza). Their relationship is mutually beneficial:

• the fungi network (mycelium) spreads its strands into the surrounding soil, extracting nutrients, minerals, and water from a large area which it then releases to the plant;

• the plant creates carbohydrates, energy, and fatty acids through its photosynthesis process and feeds these back to the fungi.

This symbiotic relationship connects the fungi to other surrounding plants, creating a (chemical) communication network that can cover large areas.

The largest known living organism in the world is the mycelia of the parasitic honey fungus (Armillaria ostoyae) in the Blue Mountains of Oregon, USA. It’s believed to be somewhere from 2400-8000 years old and covers over 9km²; that’s 960ha, or approximately 900 rugby fields if you include the sidelines and in-goal areas.

Mycorrhizal fungi often produce fruiting bodies near the roots of their chosen plant companion. Their mycelium can be very fine, so often the only way to see it is to use a microscope.

Ectomycorrhizae

Inkcap (Coprinellus sp), decomposer

These mycorrhizal fungi fruit above ground and are generally associated with trees.

Fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), the classic fairy tale toadstool, is an ectomycorrhizal fungus often found in pine plantations. It also forms relationships with trees such as oak, spruce, fir, birch, and cedar.

Another well-known and edible species is the birch bolete (Leccinum scabrum), found under birch trees.

Endomycorrhiza

Leratiomyces ceres, also known as chip cherries, decomposer

In the vegetable garden, you’re most likely to have arbuscular mycorrhizal or AM fungi, part of the endomycorrhiza group.

These don’t produce above-ground mushrooms and aren’t visible to the naked eye. Soil scientists are still learning about AM fungi, but we do know they’re the most common symbiotic fungi-plant relationship. It’s thought that 80% of all land plant families have an AM relationship.

Saprophytic

The majority of mushrooms you’ll see in your garden are saprophytic, the decomposers, the most common type of all fungi. This group includes the common field mushroom, Agaricus campestris.

They live on dead organic matter, breaking down chitin, cellulose, lignin or woody matter, leaf matter, manure, and dead insects. This process creates humus and mineralised nutrients which plants can utilise.

Soft-bodied, delicate fungi are usually the first to show up in mulched areas, such as common inkcaps (Coprinellus sp). These digest the most readily available nutrients, making them more bioavailable to the plants.

We’ve experienced flush after flush of these short-lived mushrooms in our garden. Their delicate heads push up through the mulch, open like flowers, then dissolve into a black goo which gives them their name.

Leucocoprinus sp, decomposer

Another little relation, the fairy inkcap (Coprinellus disseminatus) forms tiny clusters along the edges of the garden beds. We step around them to avoid damaging their fragile beauty.

As mulch ages, larger, chunkier mushrooms begin to appear. These can access and digest nutrients within the cellular structure of a woody mulch as they have a more vigorous mycelium and powerful enzyme excretions.

These species often include the common, brick red Leratiomyces ceres, also known as chip cherries (a rather fitting name). They’re bright and cheerful as they spread out over the mulch, but don’t let them fool you – they’re not edible.

Another interesting fungus commonly found growing on woodchip mulch is Cyathus striatus (fluted bird’s nest or splash cups). They’re named for the tiny nest-like cups they form which contain a few peridioles (spore capsules) that look like little eggs. These curious fungi are so well camouflaged by their colours and size, they’re easy to miss unless you’re weeding or fungi hunting.

Saprophytic fungi form the most easily-seen mycelium. Lift mulch or dig into compost, and you’ll see thick, white clusters of hyphae, a vivid white against the dark browns of decomposing wood.

Fresh mulch on a garden pathway.

Pathogens

This is the second-largest fungi group in gardens and probably the most studied. These can be present as rust, root rot, brown rot, blast, smut etc.

While many resources are directed towards fighting these fungi, they’re part of nature’s cleanup crew, breaking down plant mass.

If they’re attacking your plants, it’s a clear signal something is missing or out of balance in your soil. The healthier a soil becomes, the greater the resistance plants have to fungal pathogens.

Fluted bird’s nestor splash cups (Cyathus striatus), decomposer

The cleaners

Some fungi have ‘cleaning’ functions, making them a valuable tool in the battle against pollutants. Mycoremediation is the process where fungi transform environmental toxins such as heavy metals, petroleum, herbicides, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and others using digestive enzymes to degrade them into generally harmless compounds.

However, these compounds can accumulate in the fruiting body in some cases. Shaggy ink cap (Coprinus comatus) is a common edible mushroom that can remove mercury from soil, but it can reach toxic levels as it accumulates.

Don’t eat fungi from contaminated sites, even if they’re normally considered edible.

The fairy inkcap (Coprinellus disseminatus), decomposer

The edibles

There are several popular edible mushrooms you can grow. Most grow on logs such as oyster, shiitake, and tawaka.

The most impressive that thrive in wood mulch is king stropharia (Stropharia rugosa-annulata, also known as wine caps or burgundy mushrooms). These can grow to a spectacular 30cm in height and diameter.

They’re a strong decomposer with a dense mycelial mat, breaking down wood mulch into nutrients for plants and creating beautiful soil. They’re also capable of greywater filtration.

Buy spawn for wine caps (available to buy online) and mix them into a bed of thick wood mulch. With adequate moisture and mulch, they should begin fruiting within 2-12 months and continue to provide you with plenty of mushrooms for many years.

TOO MUCH OR NOT ENOUGH

The white mycelium that grows below the mushroom is the main body of fungi.

Often in ‘conventional’ gardening and farming practices, the beneficial fungi and other microbial life forms struggle due to:

• frequent soil tilling;

• fungicides, pesticides, and herbicides;

• regular fertiliser application, especially soluble salt fertilisers;

• overgrazing, which destroys the fragile fungal networks and their relationships with plants.

Walk through old bush and you’ll see just how diverse and amazing these fungal networks can be. But a forest’s highly fungal environment isn’t what you want in a food garden or orchard.

This is where succession comes in. It’s where one ecosystem replaces another as the soil and environmental conditions change and plants respond to these changes.

Soil scientists studying the microbial world have shown bare rocky soil is highly bacterial.

As you move through soil types, the ratio of fungi to bacteria increases through each stage. You see plants like scrambling annuals, then deeper-rooted annuals, and annual grass species.

Tawaka (Cyclocybe parasitic), decomposer

Just before the 1:1 B:F ratio (Beneficial Bacteria to Beneficial Fungi ratio) – where perennial herbaceous plants and grasses thrive best – you get the soil life that supports nutritious vegetables.

The ratio of fungi increases as you move to environments that suit woody perennials, shrubs, and vines (1:2 to 1:5 B:F), then orchards (about 1:10). Deciduous trees like a range from 1:5 to 1:100 B:F. Evergreen and old-growth forests are highly fungal at 1:100 to 1:1000 B:F.

If you look at what’s currently thriving in your garden, you can work out roughly where your soil’s B:F ratio is at and then make changes.

It’s also important to limit the practices that harm fungal networks (eg tilling), increase the use of mulches, and add a diverse range of plants.

There’s a whole new world to explore beneath your feet, and bringing back the fungi is just a starting point of the soil health journey.

Ramial woodchips and straw spread around the vegetable beds

WARNING

Identifying edible mushrooms is very tricky. There’s a high risk of being poisoned by the many toxic types you may see in your garden or in the wild. Don’t rely on photos or the internet to identify fungi. Always get a correct identification from an expert before eating any fungi, even if you feel certain.

WHY YOU WANT THIS MULCH

Mulch is typically used to retain moisture during drier months. In our garden, it also allows excess water to run away from mounded garden beds in times of high rainfall, soaking into the pathways that run between them. It also forms a barrier that prevents weed seed germination and makes any that grow easier to remove.

We mostly make ramial mulch. It’s made from freshly cut branches, up to 7cm in diameter. These are mulched while the cambium layer is still green. Often leaf matter or tree buds are included, adding more nutrients to the soil as it decomposes.

Ramial mulch provides more nutrients and helps change the characteristics of the soil to a less weed-friendly environment compared to normal woodchips. Scientists aren’t sure why but believe it may have an allelopathic effect, releasing compounds that inhibit weed growth.

This younger, fresher wood has the optimal balance of carbon to nitrogen, becoming higher in carbon as it ages. Mulch made from older wood can result in a ‘nitrogen deficiency’ where the woodchip and soil meet.

Some scientists believe that because the wood is already high in carbon, microbes breaking it down compete with plants for the available nitrogen in the soil. You can negate this by adding nitrogen to the soil before you mulch (eg, blood and bone, aged manure) when you add the mulch or use ramial mulch instead.

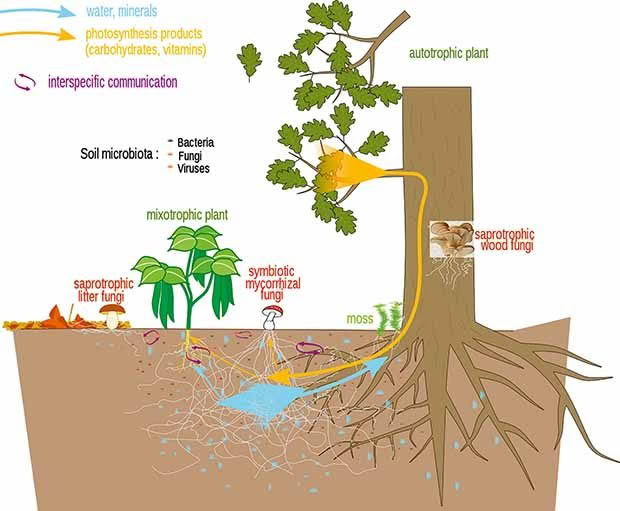

THE MYCORRHIZAL NETWORK IN YOUR GARDEN

Mycorrhizal fungi are in a symbiotic relationship with plants. The relationship is usually mutualistic:

• fungi provide the plant with water and minerals from the soil;

• plants provide the fungi with photosynthesis products, eg carbohydrates.

However, some fungi are parasitic, taking from the plant without providing benefits. Conversely, some mixotrophic or parasitic plants connect with mycorrhizal fungi to obtain photosynthesis products from other plants.

Finally, saprotrophic (or saprophytic) fungi live on dead organic matter without forming a symbiosis with plants.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.