A crown jewel in Northland: The Moretti family lives in isolation running the 3000-hectare Mimiwhangata Coastal Park

A family which counts itself lucky to be the keepers of a DOC farm in an unspoiled coastal wilderness shares it every summer with holiday campers.

Words: Polly Greeks Photos: Jane Dove Juneau

Originally published in the Jan/Feb 2011 issue of NZ Life & Leisure.

The dusty road linking the Moretti family to the outside world secures the rest of New Zealand to something that’s just about vanished.

“It’s a way of life you might have found in the 1950s,” Chris Moretti says, reflecting on his family’s lifestyle at Mimiwhangata Coastal Park. “This is one of the last places in Northland that’s pretty much untouched.”

Getting there involves a winding drive over steep hills terraced by cattle hooves before the increasingly narrow dirt road descends through native bush. Around a bend, the view suddenly spreads its arms wide to the Pacific Ocean as the trail dissolves amidst great sweeping arcs of white-sand beaches strung between rocky headlands.

On one side of the peninsula the surf’s hollow song surges in while on the other gnarled pohutukawa lean over turquoise bays where tiny waves lap at the stillness. Tui notes drip nectar-sweet from pockets of bush and the night calls of kiwi and morepork echo over black-shadowed land.

There are cattle and rare native ducks, a capering farm dog, visiting dolphins and boys with sun-bleached hair who disappear outdoors from dawn until long after dusk, roaming wild on adventures that end only when hunger drives them in.

Cows graze near the barely used airstrip.

The Department of Conservation calls Mimiwhangata one of the jewels in its coastal crown. For Ngati Wai it is an outdoor cathedral but for Chris and Nadeane Moretti’s three sons, Joe, Paul and Ben, the 3000-hectare seaside farm is simply known as home.

The family shifted onto the property a decade ago, following Chris’ appointment as its DOC ranger. At the time he was managing a private training establishment offering alternative education opportunities to those struggling in mainstream education and was feeling the pressure of the job.

The farm’s population of pateke (brown teal) is carefully monitored by DOC.

“It was a good lifestyle change,” he says, noting that his physical and mental malaise vanished the day he relocated.

it’s a 15-minute drive just to reach their letter-box, Chris and Nadeane were well acquainted with remote locations before they arrived, having spent three years on Stewart Island where Chris was a paua diver at the start of their relationship. The Marlborough Sounds area was also home for a number of years while he worked as an Outward Bound instructor at Anakiwa.

Nadeane’s vege garden keeps the family well fed.

These days his duties are to manage the coastal farm park and a DOC camp ground, as well as three houses available for rent as holiday accommodation. A local farmer owns the livestock, paying DOC per head of cattle for the right to graze there. It is rare, Chris says, to encounter coastal farms these days.

“There’s not a lot of money in it.”

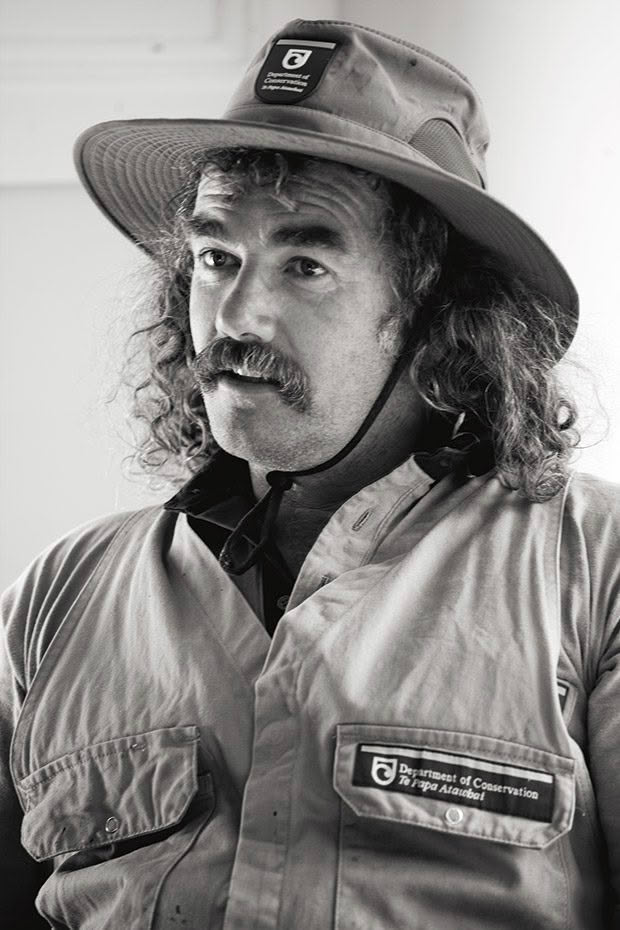

Chris Moretti.

Rare, too, is the sort of camp ground found at the park. Separated by a pohutukawa-smothered headland and accessible only by foot, the sheltered crescent moon of Waikahoa Bay offers composting toilets and a cold-water tap but, despite the lack of amenities, the 36 camp-sites are full from Boxing Day until the end of January.

Nadeane shakes her head at the popularity of the place.

Nadeane and Ben feed the calves.

“The camp ground opens on the first of September and by the end of the day it’s fully booked for summer. The phone runs hot.”

It wasn’t always so. When the Morettis took over the camp ground it was bringing in barely $6500 per annum. Last year it earned $34,000.

“Now it’s like a village over summer,” Chris says. “It’s a whole heap of people with really varied backgrounds. They come for a couple of weeks at a time, year after year. We’ve seen babies grow up.”

It is, Nadeane says, a highly social time for the family and provides a nice balance to the winter months when everyone focuses on the farm.

The Marine Report commissioned by New Zealand Breweries in the 1970s declared Mimiwhangata to be “beautiful, rich and varied to a degree probably unsurpassed anywhere in New Zealand”.

Although some ecologically minded people may tut-tut that the property is run as a farm, Chris says it provides visitors with an experience of nature many have never had before.

As well as the immense sense of space the open land affords, there are walking tracks between bays, pretty streams draining into small estuaries, stands of fenced-off bush and dunes, wetlands, healthy populations of sea and forest birds, more than 20 kilometres of shoreline designated as a marine park and ponds which are home to one of the world’s rarest water fowl, the brown teal or pateke.

The Moretti boys used to ride their horses around the property but now they prefer riding the waves just beyond their back door.

Chris says the rich archaeological landscape offers a journey in time from early settlement to the present day.

“The way I see it, if you manage the farm the right way then everything else out here that’s special is cared for and protected. My title here is ranger but I’d rather have the title of kaitiaki, or caretaker.”

At weekends Chris drives them around the North Island to take part in surfing competitions.

Mimiwhangata has been a farm since the 1840s. Recognizing the beauty and potential of the land, New Zealand Breweries bought the property in 1962 and funded extensive archaeological, ecological and marine surveys.

“They had huge plans to turn it into an eco resort but it was before its time and there was considerable opposition to it, particularly given the significance afforded by the surveys,” Nadeane says. “Then they created a charitable farm park trust in 1975. In 1993 it was handed over to the government in exchange for land in Wellington.” It has recently been gazetted as a scenic reserve which furthers DOC’s power to protect it.

The Morettis live in the farmhouse which was built in 1923 to replace a burned-down predecessor. With a deep porch facing the sea, it’s a sturdy wooden structure surrounded by scratching bantams and rampant geraniums spilling over the fence.

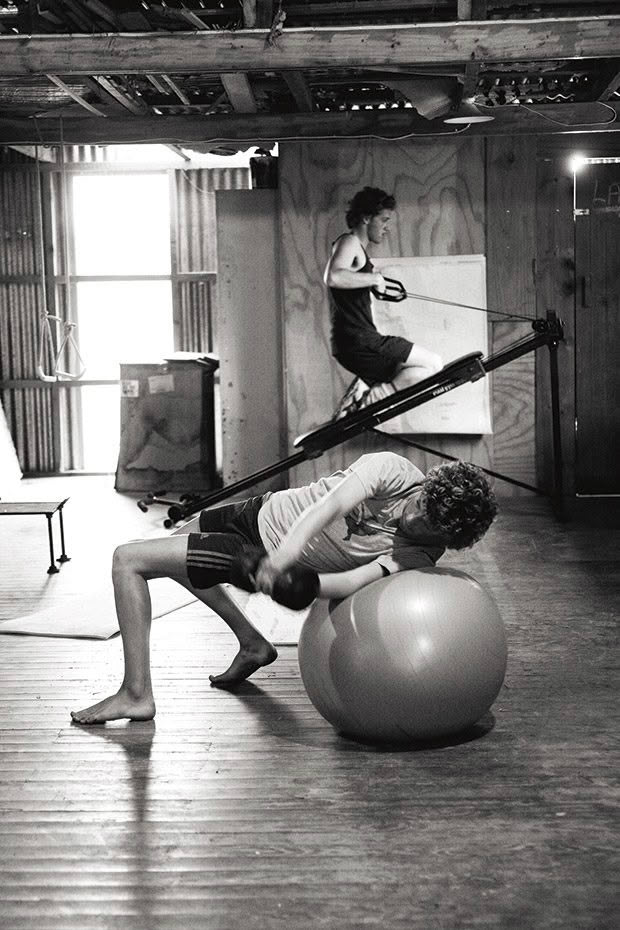

Joe and Paul have constructed a gym in the woodshed.

There are fruit trees planted by Nadeane – guavas and bananas, feijoas and macadamias, all doing well in the harsh coastal air – and she’s also brought the vegetable patch back from the wilderness under which it had been smothered. She drives to Whangarei once a fortnight for supplies.

“We’re pretty self-sufficient. We have our own meat, there’s plenty of seafood and the chooks give us eggs. We keep a hive as well.”

Down by the gate, the wetsuits hanging under a pohutukawa tree belong to Chris and the boys.

“It’s all been a big adventure,” Nadeane says of her sons’ lives. “The boys have never really known the word ‘can’t’.”

“Surfing’s the kids’ lives,” Chris says.

It’s something at which the older boys excel which is no surprise, given the surf break on their doorstep and the hours they spend on their boards. The sport also provides them with a social life. Joe, aged 17, and Paul, 15, regularly take part in competitions, following the national surf circuit around the North Island in an old bus driven by Chris.

Last year Joe represented New Zealand in Ecuador, taking two terms off school to raise the funds and still managing to pass his sixth-form exams. He and Paul both study via correspondence and, as well as being motivated with their studies, are exceptionally hard workers around the farm, according to their proud father.

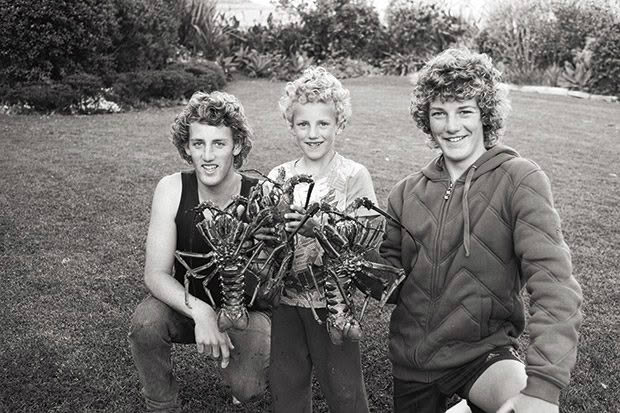

Joe, Ben and Paul with a clutch of crayfish.

Despite a lack of friends when they were younger, Joe says the lifestyle has more than made up for it. “And I’ve gained a whole bunch of useful skills – fishing, diving, hunting, sailing and surfing.”

Six-year-old Ben was born on the property, prematurely at 26 weeks, and it’s the one time Nadeane felt the family’s geographical isolation. An emergency plane ride down to Auckland Hospital and a spell of confinement followed the birth, but watching the high-spirited child race about the farm now it is hard to believe he ever suffered health problems.

The giant pohutukawa is of special significance to Nadeane and Chris as their newborn daughter’s ashes lie beneath it.

Whether it’s the home-grown diet or the sea air, the entire family seems particularly clear-eyed and vibrant.

“We’re pretty healthy,” Chris agrees. Unlike his brothers, Ben attends a local school which involves a daily ride on the back of a quad bike across paddocks and through streams to a neighbour who ferries her child and Ben to the rural school bus-stop.

Paul shows off a possum whose fur will provide him with pocket money for surfing trips.

Emphasizing Mimiwhangata’s unique link to the past, Chris refers to one of its regular visitors, an 85-year-old man who takes great delight in the fact the place has changed so little from when he came as a boy.

While he knows he can’t stay on the land forever, Chris hopes his own sons can one day return and find the same length of pristine public coastline.

Ben helps out in the kitchen.

However, he’s also painfully aware that places such as Mimiwhangata are fast becoming relics. He rattles off the names of tracts of coastal land renowned for their beauty which have recently been subdivided, including a nearby peninsula sold to a Russian millionaire.

“New Zealanders don’t really realize it yet but this is a real piece of history.”

For a moment there’s a sense of urgency as he tries to impress the land’s role as a bridge to a fading past and then he grins philosophically. “I’m just glad we got to be a part of it.”

FIT FOR A QUEEN

While the scenery of Mimiwhangata was once deemed fit for a queen, cowpats were most certainly not, which is why some poor soul was given the task of removing them from the beachfront the day Queen Elizabeth came for lunch.

Sailing into the bay on the royal yacht Britannia in the 1970s, Her Majesty and family spent a couple of days picnicking at what’s known as Queen’s Corner, while the Duke drove himself around the peninsula to Okupe beach, the location of the three properties available to rent at the coastal park.

The family farmhouse.

One of the holiday homes, known as the shearers’ quarters, was once home to shepherds and before that was inhabited by a couple who raised eight children there. All three houses, as well as the Moretti family farmhouse, now use solar power for their hot water.

A BEAUTY OF A BATTLE

Despite Mimiwhangata’s breathtaking beauty, the land’s name bears no reference to it. Instead, it refers to a time long ago in Ngati Wai’s history when a mighty battle took place there.

One hundred and twelve archaeological sites have been identified on the coastal farm, including middens, pa, burial grounds and stone structures relating to this time and earlier occupation.

While a Treaty of Waitangi land claim by Ngati Wai for the region has not yet been processed, Chris says he has enjoyed support in his role as Mimiwhangata’s caretaker by local kaumatua and kuia.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.