The couple finding a lifetime of peace in Hawke’s Bay

The symmetrical formal façade of the nearly 100-year-old concrete house on the outskirts of Havelock North belies the approach of its owners of 25 years, Mac and Pip Macpherson.

A pair of serial entrepreneurs are right at home in the province where they were born. They have never lived elsewhere — maybe they just didn’t have time to consider moving?

Words: Kate Coughlan Photos: Tessa Chrisp

When Mac (John) Macpherson was a fresh-faced English literature grad, working in industrial relations at the country’s biggest meat works, Whakatu in Hastings, his uni friends taunted him with postcards sent from their travels to the most exotic places in the world. So, he’d send one back.

“Generally, a postcard of the Hastings clock tower or Fantasyland —Hawke’s Bay answer to Disneyland at the time.” Mac might have been tempted to join his mates abroad, but for a few factors — the most important being a girl from Havelock North, his girlfriend then and wife now of 32 years, Pip.

She was the Jeans Queen of Hawke’s Bay, and the three stores she managed sold truckloads of Levi’s and iconic 1980s brand Holiday Tees. Mac, an entrepreneur who tied enough fishing flies in his teens to create a sizeable house deposit for the couple’s first home, was asked to help investigate the business potential of a new-fangled device called a pager. An acquaintance had spotted one in Britain and wondered if it might have the potential alongside those other “modern” communication methods of the fax and the telex. Letters and telegrams were giving way to telexes (tape-driven and phone-connected printers) and fax machines (a printer that spat out a facsimile of what was fed in at the sender’s end). Mac did the legwork to see if a pager could be useful in the finance industry. The idea was that subscribers would pay for money market and foreign exchange data sent to the pagers.

“I know it has a formal look about it, but trust me, there’s been nothing formal about how we have lived here. It’s a big house that comes alive when it’s full of people. We love it when our children are home; their friends are here, and extended family is staying over Christmas … there’s more than enough space for everyone, with so many spots inside and out to entertain. I love seeing kids running round the front lawn or having fun in the pool.”

“Could they be useful or what?” says Mac of the roller coaster that followed. “We fed endless data into the machines, updating them every 30 seconds. Suddenly, traders could go to lunch without missing vital shifts in foreign currency rates. Bankers bought them, exporters bought them, and high-net-worth individuals bought them. The business, Infoscan, became very successful, very quickly.”

Fast-paced growth followed: first, Australian partners and a new joint-venture company, MarketSource, followed by a push into Southeast Asia. Then, global multimedia giant Reuters took an exclusive partnership for the region. Before Mac knew it, business was booming.

“It was an amazing time. Mac started that in his early 20s, and he travelled all the time,” recalls Pip, who was more than busy herself clothing the hip youngsters of the Bay.

“We had no money; I slept on people’s floors when I started the business,” says Mac. “By the time we were in our 30s, the business had culminated in a global licence as Reuters’ preferred partner for mobile financial data.”

The bronze huia feather sculpture is by Paul Dibble, and Dick Frizzell painted the wooden presentation case it sits on. This combo was a family gift for Pip’s 50th birthday. Each dark Perspex plane on the wall, by artist Michele Bryant, is etched with the name of a favourite place the couple has visited worldwide.

Was this enough for the busy duo? Mac returned from a six-week stint overseas, and they celebrated with dinner at a much-raved-about local eatery, the Clive Grapery, located in the old Clive drapery store. Hawke’s Bay being a small place, Pip knew one of the waitresses, and when she remarked that it was a cool spot, the waitress told her to buy it as the founder had recently suffered a heart attack.

That was Wednesday. By Monday, Pip and Mac owned the Clive Grapery’s land, buildings and lease. They knew diddly squat about the restaurant world except for what they’d learned during school holiday jobs as waiters at Vidal Winery restaurant — then Hawke’s Bay’s smartest venue. However, they were well-travelled diners and thought the local eating-out scene was due for a shake-up.

‘Ingrid Bergman’ roses, visible from within the sitting room, survived the couple’s rose ban. They’d over-indulged in a previous property and had 400 bushes. “It took us a whole weekend to deadhead them. That’s not living.”

“At that time, restaurants were either fine dining with white tablecloths, candles and violins in the corner, or steak bars. We travelled a lot and had come to enjoy casual dining — with great food, a vibrant spirit and no stuffiness,” says Mac.

They say their strength was finding the right people to work with them and working as hard as their employees to make everything hum. And hum it did; Clive Grapery is still recalled fondly by people who loved it then and wish it would reappear.

All 90 seats were booked out three weeks in advance, from Thursday to Sunday for five years. That was in the 1990s, and Pip and Mac were going for it.

“We both worked our arses off with 90-hour weeks. But it was pre-family. In fact, we married at the Clive Grapery when I was 27 and Mac was 30,” says Pip.

The house was renovated 24 years ago and has hardly been touched since. ”Most of the furniture is still the same, and that’s saying something considering the three big, boisterous children we’ve raised here,” says Pip. “When we were doing the house — especially the kitchen — we’d ask, ‘Will this still suit the house in 20 years?’ If anything was in fashion or on-trend, we weren’t interested.

“It was the busiest place in Hawke’s Bay by a country mile, with cool young staff. The Infoscan business hadn’t gone international when we first bought the restaurant but was just starting to morph into it,” recalls Mac. “Pip worked seven double shifts a week. I worked at the software business; then I’d race home at 5.30pm, put on a white shirt and tie, and get to the restaurant and do the bar during the dinner shift. Then, I’d do the bar lunch and dinner on Saturday and Sunday.

“It was exciting and addictive. Customers were so happy, and when they left after their meal, they’d be trying to connect to say thank you for their experience. That feeling is hospo at its most rewarding. Our staff loved it too, and it was a lot of fun.” Until it wasn’t.

After tending to several hectares of formal gardens in their previous property, Mac designed the grounds to be easy to maintain. The big front lawn is home to Pip’s gift to Mac for his 50th birthday, sculptures by their friend and artist Ricks Terstappen, who lives nearby.

Mac’s new Marketsource business grew to have installations worldwide and large ones — 10,000 customers in Tokyo and 5000 in Singapore, for example. He was travelling even more than ever. They started a family; first Grace (now 31) and William (29). Pip realised that the 90-hour weeks were only pleasurable without little people in their lives. After five years of running the Clive Grapery, she told Mac: “That’s it. I’ve had it. I want to spend more time at home being a mum.”

So, there they were, in their mid-30s, two entrepreneurs, two successful businesses (one sold), two children, and a cute house with a hectare of formal garden (the 400 roses requiring an entire weekend to deadhead) when Mac’s business partnership began to unravel and become litigious, and their third child Timothy was due.

The house suited a classic look; those early decisions have stood the test of time. We see so many kitchens that are ‘time stamps’. In 10 years, you’ll know exactly the era they were designed in. That wasn’t for us. We wanted to run in the other direction.”

Long story short, there was soon a second business sale, and Mac, cashed up at the tender age of 37, had time on his hands. A worrying thought, adds Pip. But what is a serial entrepreneur to do? Buy another house and one that requires a team of skilled tradespeople full-time for a year to bring the grand manor-style house, constructed in 1919 of poured concrete, into the 21st century, with all its 440 square metres of bits and pieces better than ever. Mac and Pip consulted local architect John Hoogerbrug to design a new kitchen to replace the old lean-to, and Mac got detailed about the layout of the property to ensure there wasn’t a formal flower bed nor a rose in sight — lawns, trees, hedges and edges are his keys to an easy-care property. He took an old cool store, sadly burnt out, and converted it into a swimming pool. He turned the former fruit retail shed into a slot car man’s heaven.

Baxter, a seven-year-old maltese shih-tzu cross, is Pip’s constant companion and “my fourth child — love him to bits”.

The old orchard of peach and apple trees was pulled out, much to the neighbours’ relief, due to the heavy black spot fungal load in the uncared-for orchard. (Today, 10 hectares are leased to Bostock Organics.) And, to Pip’s concern, Mac also began dreaming of other business opportunities.

“Well, he never stops thinking,” observes Pip. As Pip and Mac lived at their Ocean Beach holiday home and renovations and remodelling progressed, Mac thought about new business opportunities. This was 24 years ago, and although pundits told Mac the new “interwebby thing” was a fad and would never catch on, he wasn’t so sure. He was advised adamantly against e-commerce as it was “common knowledge that no one would ever use their credit card online”. He wasn’t so sure.

But he was completely sure of his interest in wine; he’d tested a fair bit of good and bad wine by this time. Advintage, launched in 1999, was a brick-and-mortar retail venture (though very non-posh) with an online component from the start.

Within a few years, Mac found himself regularly in demand to address marketing forums about his e-commerce success.

Son Tim, briefly home from life in Auckland, works in sales and marketing in the motor industry.

“I’d say, ‘In 15 years, this is how most people are going to shop’, and the audience would be sceptical. ‘Mate,’ I was told often, ‘No one is going to put their credit cards into a computer. It’s not going to work.’”

Early-adopter Mac proved them wrong and though the business started with faxed wine sale offers; it quickly became a powerful online retailer of domestic and international wine.

In typical Mac and Pip style, there’s no highbrow nonsense in the business. They both work in it and have since the beginning — Pip lugging crates of wine weighing 15 kilogrammes, though she does ask herself these days why.

Mac and Pip had long dreamed of a walled swimming pool when they realised a derelict cool store and packhouse could be converted to precisely that. And it is where they spend much of their time over summer. “If we ever leave here, this will be the part of the property I’ll miss the most,” says Pip.

“The whole point of Advintage is to take the wanky factor out of wine. We are one of the bigger wine businesses in the country and hang our hat on being a great place if you have $12 to $25 to spend on a bottle. If a customer says, ‘I want a good chardonnay, and my budget is $30’, we pride ourselves on selling them a $25 bottle where they think a $35 wine should be.”

Their slogan, “I’d rather drink plonk with great people than drink great wine with plonkers”, hangs above the retail counter in their Havelock North store and imbues everything they do in business and life.

Now that they’ve established a good team and are almost redundant in their own business, Mac again has a bit more time to think. Pip is eyeing him interestedly.

“He’s always thinking; has always been like that. And he can do anything he turns his hand to,” she says. “I’m a lucky girl.”

Is there anything he can’t do? “Listen to his wife,” she says, and chuckles.

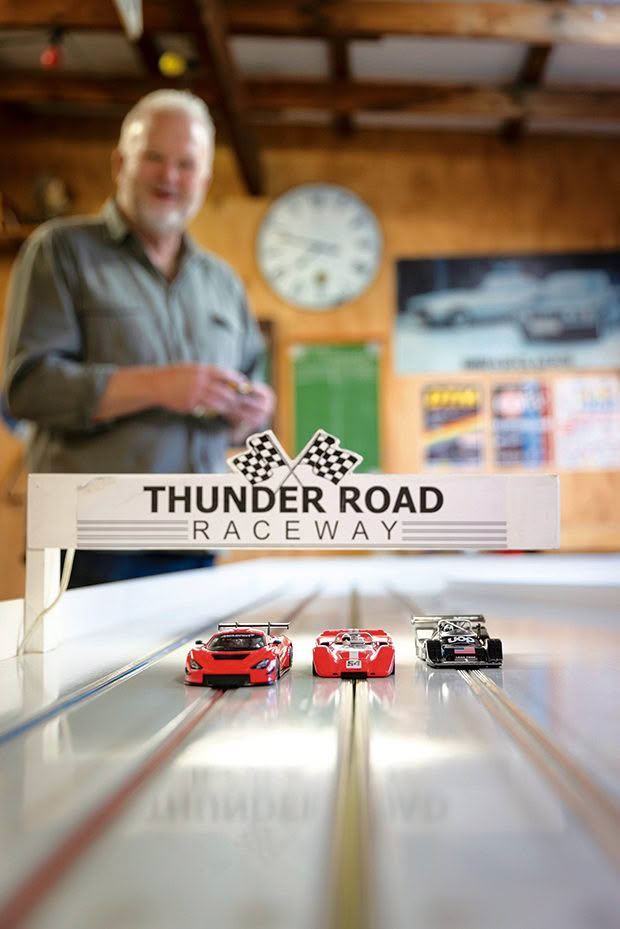

SLOT CAR NUTTERS

Few people have built a 35-metre, digitally timed, wooden slot car track in their backyard shed. “And not many would want one,” says Mac. “I still have no idea how this has become such a big thing for me, but it’s a wonderful pastime, and I love it. It helps if you are obsessive about tiny details. It’s like building Swiss watches that you race the heck out of. Hobbies are cool.”

Mac: “When I was a kid, there were commercial slot car racetracks in every town in New Zealand. After school, kids flocked to them, paid 20 cents and got 20 minutes of live track time to race. When all the kids had buggered off, older guys would come in at night with modified cars and race very competitively.

“Our local club has 20 members and four to six tracks in private ownership. We are slot car nutters, racing the cars to specific rules. Some guys, like me, take it pretty seriously. I am there to win, although some are just there for the camaraderie.”

How it happens: “You buy a car off the shelf, put it into the workshop (and laugh at yourself saying this because you are the workshop) to transform it from a toy slot car like an English-brand Scalextric into a Swiss watch that handles like a dream on the track. Tuning makes a difference, like night and day.

“I remove the wheels, gears and motor and replace them with aluminium gears and wheels, a lightweight alloy axle and a different motor, so the only original part is the body. Then the head engineer (that’s me, Mac) grinds obsessively for hours on a lathe to reduce the tyres by a fraction of a millimetre.

“In my world (says Mac — now driver Mac, not head engineer Mac), if I am racing you and I am beating you by a 1/10th of a second per lap, I am not beating you; I’m killing you.

“I know, it’s a crack-up, and I know how weird it all is. I never normally talk slot cars to anyone as they imagine a little table or a wee plastic track running cars around.”

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.