The basics of firewood harvesting and storage from an expert

The ins-and-outs of keeping the best firewood for your homestead.

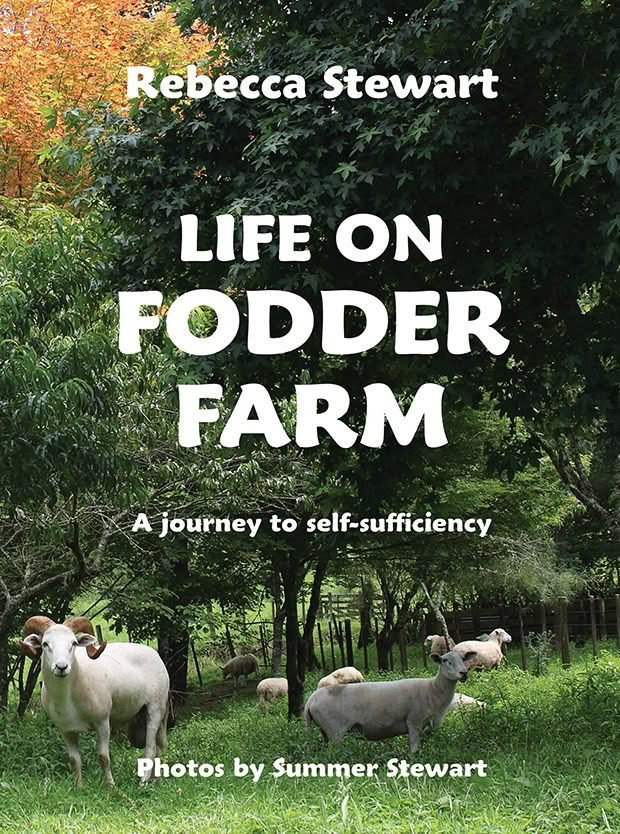

Words and photos: Extracted from Life on Fodder Farm by Rebecca Stewart.

The nights are growing chilly, and we are starting to light the fire in the evening. Firewood is an extremely important resource for us; it not only heats our home, but also all our hot water via wetback and over the cooler months we use our woodstove for cooking. We do have a gas stove, but the gas is an outside expense, and the wood is a homegrown sustainable resource.

Over summer we have been lighting the fire most mornings to warm the water for the day and leaving the house wide open. Until now it has been too hot for evening fires, we can’t leave the French doors wide open at night as the bugs inundate us.

These cooler nights are the time that many people begin thinking about their firewood stores. But for those of us living off the land and reliant on our wood burners, this year’s wood should already be dried and ready to burn. Leaving it till the cold sets in could leave us with smoky fires which struggle to warm the house and a sooted-up flue. Better still, we aim to have at least two years’ worth of wood cut, with at least one year’s worth dry stored.

We are fortunate to have a property with many trees; it was one of the reasons we bought it. Trees, water, privacy and land – those were our main requirements – we have all of them here. We also have serious quantities of pine slash, post pine harvest. This is actually a good wood for our fireplace as often hardwood creates a too-intense heat for cooking in the woodstove. Good dry pine can keep the oven ticking along at a nice even temperature.

Getting our wood well dried starts most often in the previous winter. Cutting at low sap is traditional advice when firewooding. The winter to early spring, while deciduous trees are dormant, is the main harvest time for firewood and timber for woodworking. Trees were coppiced at low sap for various timber uses and regrowth from the stumps occurred in spring. This created a regenerating timber and firewood source.

It is also thought that at low sap the moisture from the tree is lower as it is in the roots, not the trunk. Whether this would apply to evergreen trees, I am not sure, but a common view held by the forestry industry is that there is no real difference in seasonal moisture content and that trees, in fact, hold a relatively constant moisture content all year round.

Another line of thought is that cutting down a tree in sap run can actually speed up seasoning/drying time, due to the tree effectively ‘bleeding out’. But deciduous trees lose their leaves over low sap/dormancy, which can lower the weight of the tree and make cleaning up easier. However, if you are making full use of the tree, ramial wood mulch can be made from branches under 7 centimetres in diameter, with or without the leaves. In full leaf, there will obviously be a higher green matter content to the mulch and the fresher the branches, the more nutrient available for the soil. Lots to consider – and you thought we were just getting the firewood in.

But probably one of the main reasons we start the previous winter is firewood can be hard and heavy work. Cutting, moving and stacking firewood over the cooler months can be easier than doing it in the heat of summer. It is also the downtime for many other farm jobs. And you have a higher appreciation of the results when you enter the warmth of the house after hours in the cold. There are of course other factors for the timing of firewood cutting.

Pruning done at any time creates potential firewood or wood mulch and can be specific to what season suits each particular tree. Fruit trees are a good example of this with stone fruit usually pruned in summer to avoid disease and pip fruit pruned while dormant in the winter. Our pine slash is already down so the main issue we have with collecting it is the state of the paddock. Over winter it is too wet to drive across so we can only bring the wood in once the land dries out. This pushes our firewooding out to late spring, but as the wood has already had time curing in the paddock, it dries fast once stacked. Generally, our schedule is to cut wood in the winter or early spring, dry it over summer and get it into the shed by March ready for those cooler nights.

When pruning or felling trees we will often just pile the firewood, cut into rings to our woodstove length, near where the tree was. The rain washes out the sap that keeps the wood green and speeds up the drying time. But the issue with this is that many trees are best split soon after felling as they can harden over time and if you are hand splitting with an axe it is easier to split the wood fresh.

As the land dries out, we can drive around the paddocks collecting the firewood. It is brought up to the home paddock, split and stacked on a row of pallets to keep the wood off the ground and allow airflow underneath. A tidy outer wall layer is stacked with attention put into stabilising or ‘locking in’ the corners with crossover pieces. It’s like building a 3D jigsaw. Most of the wood is either flat, triangular, half-round or round and can be fitted together to make a stable structure. The gap in the centre is filled with all the odd shaped, short and knobbly bits. These are put in randomly, but the space needs to be filled as you stack the walls and be relatively closely packed to support the walls. Air will still flow through as there will be many small gaps in the stack. Once the stack reaches about 1.2 metres, we create a slight pitch along the length and place several sheets of old corrugated iron on top. The pitch allows for water runoff from the iron roof, and we weigh it down with some heavy chunks of wood.

This structure is very stable and can be built in a paddock where the livestock are. Our house cow might occasionally try to knock it around a bit but the structure stays standing. The size of the stack, which is the width of a pallet and usually four or five metres long, means we can stack a large quantity of wood, in a relatively compact space. Most firewood stacking advice that I have seen says to singlewidth stack. While this works, for us it would take up too much area, be less stable in the paddock and be difficult to put a corrugated iron ‘roof’ on. The corrugated iron provides a heat sink that warms and dries the air inside the pile, while keeping most of the rain off. The outside of the stack remains exposed to the elements especially wind and sun, which help dry the wood. We find the stacked wood is ready to be transferred to shed storage in about three to four months. It will be bone dry and excellent burning. Bone dry wood burns hotter, for longer and, when the fire is shut down, turns to charcoal, which creates a low burn to last through the night.

If you forego this step and move the wood straight into the shed, you are more likely to end up with damp, mouldy wood. Burning wet or unseasoned firewood produces less heat and can cause creosote build-up in your flue, especially with softwoods, which can cause chimney fires. Taking the time to ensure your wood is fully dry before putting it in the shed can save you time and wood in the long run. Once shed-stored, it should stay dry, as long as the roof doesn’t leak, the shed is north or northwest facing for maximum sun, and it allows for airflow.

A simple, cheap shed design is a corrugated iron roof on four 2-metre-high (or higher) posts. Cover the ground with pallets to let the air flow underneath and keep the wood off the damp, cold ground. Hurricane netting can be used around the outside ‘walls’ to hold the wood in but still allow airflow and, if necessary, a wall can be built on the prevailing rain side or to the south, but keep the sunny side open. Any wood on the outer edges that gets rain-wet will soon dry on a sunny day if it was dried well before going in the shed.

It is a good idea to have at least a week’s worth of wood close to the house in the event of bad weather. Trudging across a paddock in the rain with a wheelbarrow-load of firewood is not cool for you or the wood.

There are many views on firewood and systems to manage it, but this suits us and provides us with plenty of well-seasoned firewood throughout the year.

SUSTAINABLE FIREWOOD

The existing trees on our property are our first resource for firewood. I’m not saying we go and cut them down, there are other, better ways to get firewood. By identifying and learning about what trees we have and how best to manage them, we can source firewood by pruning them, lifting branches or thinning out some trees if planted too close. If they can be coppiced or pollarded, it will increase our firewood capabilities as they rapidly regrow from a developed root system. Owning a property with trees is an amazing resource and removing trees should only be done if they are a risk or negatively impact their surrounding environment.

Having assessed the existing trees, we are now working on planting a sustainable wood and feed lot, hedgerows and large multipurpose orchard and nut groves. These can provide not only firewood but food, livestock food, garden mulch and stakes, fencing materials, timber and a beautiful landscape. As we already have a massive amount of pine slash firewood available, many of the plants are being grown from seed, cuttings and locally sourced saplings.

Any trees we plant must be multipurpose, which maximises the use of the space they occupy – fruit and nut trees are a great example of this. They feed us and the livestock, bring in the birds and bees, are attractive shade trees and their prunings provide firewood. Inter-planting them with support trees, such as tree lucerne (a fast-growing firewood, stock fodder and nitrogen-fixing small tree) maximises the use of the space. Many of the deciduous trees can be coppiced, such as alders, birches, hazels, sweet chestnuts, mulberries and poplars. They provide a fast-growing renewable and sustainable resource for timber, nuts, fruits and livestock food as well as firewood. Gums have a great reputation for firewood, but they are hungry trees and do not give back to the environment in a positive way, a bit like planting conifer species. They can also quickly become hazardous if not managed well, as they tend to drop branches once they reach a large size. We believe there are much more suitable and useful trees available than gums or for that matter pines. Acacias support the soil around them through their nitrogen-fixing and mineral accumulator properties, are fast growing and as firewood are hot burning and easy to split. We especially like the black wattle and Tasmanian blackwood.

Fodder trees are well worth looking into if you have livestock, they are a great feed resource in times of drought but also provide diversity and added nutrition for your animals. If planted in areas where they are protected but next to or in paddocks, they can also provide shelter and shade – two factors that are, unfortunately, often not provided for on many farms. Here again, the tree lucerne (tagasaste) really stands out as it is a high-protein feed, drought-hardy, fast-growing and good firewood. Mulberry is another highprotein feed and, if you can beat the birds, has very tasty berries. It is also, apparently, one of the top heat-producing woods. The most common fodder trees in New Zealand are, of course, the willow and poplar. Willow makes a good fire starter if well dried but burns fast without much heat. Some poplars have good dense wood and, as they grow fast, they can be a valuable resource in a sustainable firewood lot.

Our native trees mānuka and kānuka are great firewood and fast-growing pioneer trees. They can be used with other small trees, like tree lucerne (not native), māhoe, kōwhai and pittosporums, to fill in the gaps while larger slower growing trees, like NZ beech and tōtara, are getting established, then felled for firewood when no longer needed. The older slower growing natives are best left standing; while some may be great firewood, they are not suitable for a sustainable firewood lot. It is best to choose trees that have good regrowth and nutritionally support the surrounding trees or provide some of the many uses we have mentioned.

There’s an old saying ‘The best time to plant trees was twenty years ago, the second-best time is now.’

Extract from Life on Fodder Farm: A journey to self-sufficiency by Rebecca Stewart $39.99 RRP, Upstart Press. Available now where all good books are sold.