A prickly pal: Is gorse a friend or foe?

People tend to have strong opinions about gorse, but there are two sides to this prickly plant, and Nelson Lebo has found a way to make peace with it.

Words & photos: Nelson Lebo Additional photos: Brad Hanson

Like many of those starting out on a block, our first years were marked by nearly as many failures as successes. Two steps forward, one step back.

I owned a 15.3ha farm in New Hampshire (USA) from 2000-2008. There, weed control was relatively easy because the land was 95% forest and was covered in snow for five months of the year. The worst ‘weed’ was blackberry and the best control method was to eat the berries.

It’s a tougher job in New Zealand where plant growth is all year round, and keeping up with weed control is a never-ending endeavour.

Initially, we set out to manage invasive plant species organically. We made great headway against a sizeable population of thistles or ‘spikies’ as our then two-year-old daughter called them. Regular family walks around the farm with a toddler, spade and slasher in hand, resulted in the near eradication of the worst varieties.

There was no such luck with the gorse.

Early on, we identified an area on our block suitable for small-scale commercial blueberry production, however it was spotted with individual gorse bushes. Naively – and without any research on gorse control – we simply cut it off at the base.

That only made matters worse. The gorse grew back thicker than before, with multiple stems that made them even harder to cut back a second time.

The area is now a thick gorse forest, and we’ve abandoned the idea of growing blueberries altogether.

Gorse in context

Gorse (Ulex europaeus) was brought to New Zealand by English settlers as a hedge plant in the early 1800s. Its physical characteristics made it the perfect hedging plant:

• 2-2.5m tall;

• sharp spines on its branches;

• tolerant of exposed windy sites;

• does best in acidic soils.

Unfortunately, these same characteristics also made it invasive on open hillsides.

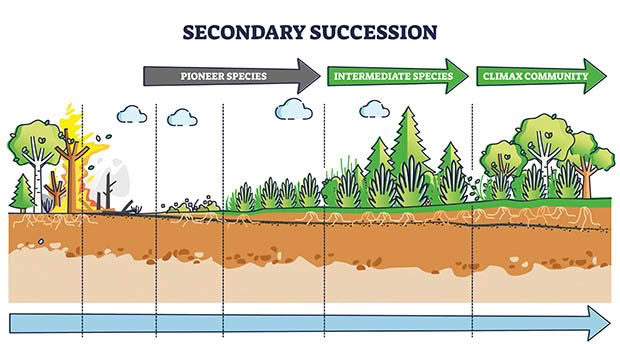

From an ecological perspective, gorse is a pioneer species. It’s the first to inhabit bare land after a disturbance of ground cover caused by a fire, slips, or forest clearing. Like many other pioneer species, gorse serves two essential services:

• it holds soil in place, thanks to its dense root structure;

• it helps build and improve soil, with root nodules that fix nitrogen.

This is the crucial first stage of ecological succession.

Gorse is a wonder pioneer plant, literally regenerating damaged land, but it’s hard for people to get past its invasive nature.

When I googled ‘gorse’ while researching this article, the first option that appeared was ‘gorse spray’, an indication of most Kiwi’s attitude towards it.

I experienced it firsthand a decade ago while presenting a permaculture property design to a whanau trust. The 4ha property included a problematic steep slope directly above a significant drain that flowed into a precarious culvert. From my perspective, the best thing to do was keep the land stable. The best way to do that was to leave the gorse already on it in place while interplanting native saplings that would eventually grow up and shade out the gorse.

When I presented that part of the design at a trust meeting, you could have heard a pin drop. Then someone spoke up. “Our father has been spraying gorse on that slope for decades and he wouldn’t tolerate doing what you suggest.”

There are a lot of people who agree. Massey University identifies gorse as one of New Zealand’s worst scrub weeds. It occupies large sections of hill country, reducing areas available for grazing livestock. It confounds foresters because it competes with young trees and inhibits access to forestry blocks.

Additionally, dry stands of gorse burn easily and fire spreads quickly.

Despite that, we still believe gorse has a place on our block.

GORSE STRATEGY 1: USE IT FOR GOOD

Poplars and gorse that survived the 2020 fire. These continue to hold the steep banks in place during heavy rain.

If you forced me to choose between fire and flood, I’d take fire – at least there’s a fighting chance.

We’ve faced both. In March 2020, an errant spark from a neighbour’s chainsaw ignited a pile of sawdust, then spread into the gorse on our block and those around us, driven by high winds.

But back in 2014, just after moving here, we learned the greatest risk we face is landslips in the steep gully above Purua Stream. You can still see the slips we experienced during 2015 and scarring along the slopes from previous heavy rain events.

One of those scars has three huge poplars growing in it. Most of the others are covered in gorse.

The best way to hold hillsides like ours in place is to let gorse do its job as a pioneer species, holding and building soil.

Under normal conditions, ecological succession takes decades, but we’re able to speed up the process with an approach I call ‘managed succession’. Like many pioneer species, gorse is shade intolerant and won’t grow or germinate underneath a canopy of its own or other trees and shrubs.

Conversely, many native trees characteristic of climax forests are shade tolerant when young, and can grow up through a low canopy of pioneers, eventually shading them out.

We’ve been able to speed things up by planting 3m poplar poles into some of the dense stands of gorse – protected by plastic sleeves where we run the goats – and good-sized native seedlings where we don’t run the goats.

This method means:

• we immediately take a decade off the clock, jump-starting the secondary growth versus waiting for seeds to germinate in the gorse litter;

• we’re able to retain the soil holding and soil building characteristics of gorse on our most vulnerable slopes.

GORSE STRATEGY 2: CUT & PASTE

Nelson’s gorse go-bag.

We take a different approach where dense stands of gorse creep outward and where individual gorse plants pop up on their own.

While some people keep a designated go-bag at the ready for potential emergency evacuation, mine is for managing gorse. It’s an old day pack with perished zippers, left here by one of our former permaculture interns. It contains loppers, secateurs, a pruning saw, gloves, and a herbicide paste called Triumph Gel. I keep it in the carport next to a doorway leading to our block’s gully of gorse.

Chopping back targeted gorse.

Cutting and pasting gorse isn’t the most glamorous chore. The go-bag makes it as easy as possible for us to do an hour here or 90 minutes there.

The result is satisfying progress. Even 20 minutes is worth it if there’s a small patch emerging at the far end of the block and I have to go there for another reason. I just grab the bag and go – combining trips – to get more done in less time.

Applying a herbicide paste to prevent regrowth; the result – dead gorse.

We don’t necessarily plan big gorse outings but instead chip away at it so as not to burn ourselves out. There is no FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) with gorse.

It will always be there waiting.

5 TIPS FOR OUT-GROWING GORSE

Gorse plants live for around 30 years and reach a maximum height of 5m; a native such as kānuka can live for more than 70 years, reaching 16m. Gorse seeds can’t germinate in shade, so if you’re patient, eventually the natives win.

That’s backed up by research. One study found gorse was vigorous in 10-year-old scrub (eg, mānuka, kānuka), senile in 34-year-old scrub, and dead in 40-year-old scrub.

Other studies have found:

• Native tree seedlings have a higher survival rate in gorse than in kanuka stands, probably because of openings in the canopy and the lower density of hares and rabbits.

• Woody native trees establish best when gorse is low in density, with a shallow litter layer underneath (mostly gorse stands over 25 years old). They’re far less likely to establish in gorse plots younger than 25 years, probably because it has a coarse-textured, deep, slow-to-decompose, dry litter layer than older gorse.

• If you use seed ‘bombs’ to help establish natives, the best seeds to use are larger ones which more easily germinate under shade than ones with tiny seeds. Options will depend on where you are in NZ, but include karaka, taraire, and pūriri.

• Once gorse starts to be shaded out (70% light or less), its growth rate falls significantly.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.