How to save precious hours on your lifestyle block

The most important resource on your lifestyle block is your time, so it’s important to spend it wisely.

Words: Sheryn Dean

You can do almost anything on a lifestyle block. Grow food, generate an income, keep horses, milk goats and make cheese. Maybe, do all of them.

But all the people I meet who live off the land agree on one thing: there’s never enough hours in the day to do everything they could, should, or would like to do.

It makes sense then to be efficient and spend your time as wisely as possible.

REDUCE YOUR ROUTINES

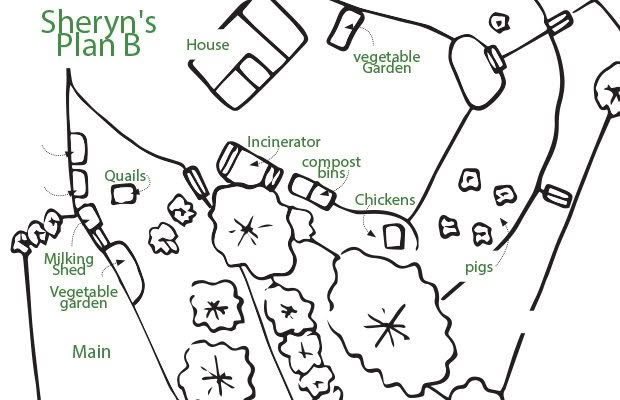

I heard this repeatedly from old-timers when I was establishing my block. Grand Plan A was for pigs there, chickens over there, compost bins back there, and orchard everywhere.

Their advice? I needed to cramp my style and cram things together.

“Compact everything. Grand Plan A means lots of fencing, and fencing is costly. And group your daily chores together, you’ll be doing them every day.”

Plan A went in the compost. Plan B still contained grand visions but revolved around a much shorter, more efficient route that went past the incinerator and compost bin to the chickens and pigs, through the orchard to the ducks and the cowshed.

These days, by the time I’ve done my round, I’ve swapped kitchen scraps for fruit, eggs, and milk. I can speed through it in 10 minutes with a basic check or take two hours if I’m being thorough. On those days, I scrub troughs and baths, hand-feed the ducks, move the quail cage, open up a new grazing break for the cows, and give the pig an extra scratch.

The system also varies according to the time of year. I walk through the vegetable garden every day and collect poultry food, but I take slightly different routes back through the orchard, depending on the season. I want to know what’s happening, what’s ready to eat, what needs doing.

Most days, I enjoy taking my time. But when it’s cold and rainy, or when I have important obligations somewhere else, I thank the old-timers for their good advice.

TAKE THINGS ONE YEAR AT A TIME (& KNOW WHEN TO STOP)

These raised vegetable beds are right outside the back door. A security light allows for night-time harvesting. I like to pick my vegetables fresh, while I’m cooking.

In the first year, I planted the orchard. In the second, I got a milking cow. Then it was the vegetable garden, ducks, pigs. I took time to carefully source stock and have the infrastructure they required properly set up for easy management.

I had to think of everything that would make life simpler and faster, such as:

• taps and hoses running to every part of the block;

• duck baths with ballcocks so they refill but don’t overflow;

• gates that swing and latch with a kick;

• paddock layouts so the cow is always near the house.

Over the next several years, I added calves, chickens, fodder trees, quails, and bees.

The beehives made me realise I couldn’t commit to it all. I was time-poor, stressed, and finding it hard to prioritise or relax. Just because you can do everything doesn’t mean you have to.

Ways to spend your time well

FIREWOOD

Here’s what a lot of people do:

• cut a tree down;

• cut it up, ring it;

• stack it;

• get the wood splitter, split it;

• re-stack it, let it cure;

• stack it in the woodshed the following season;

• cart it up to the house in winter;

• transfer it to the wood basket;

• load it into the fire.

Plan firewood poorly and you might handle it 7-9 times before using it.

You have to handle each piece of firewood seven to nine times. But you can greatly reduce your workload:

• have the splitter available as you drop the tree, so it’s cut up and split at the same time.

• stack it directly into transportable cages where it can season.

• move it (in its cages) to a shed, a woodshed near the house, or best of all, the garage.

• build a big wood storage box close to the house, so you only have to refill it once a week.

WATERING

If you spend 30 minutes, four times a week, for 20 weeks of the year standing in your garden watering during dry spells, that’s 40 hours. Every year. Now think about what you would do with an extra working week. Sounds like enough time for a holiday.

Water is important, but in the case of trees, standing there with a hose is a waste of your time, a waste of water, and it’s often detrimental to the tree. Tree roots grow towards nutrients and water. If you aim a hose at a tree, a lot of the water evaporates, and you only ever moisten the top few centimetres of soil. That encourages roots to grow near the surface, the zone that will dry out first.

Better methods include:

• adding water-holding crystals to soil during planting;

• piling mulch around trees to retain the moisture in the soil;

• have shelterbelts to reduce transpiration;

If you do have to water trees, you can use slow-leak containers. Get a 20-litre plastic bucket and drill a tiny hole in the bottom. Water slowly dribbles out into the mulch, trickling deep down into the soil.

In the veggie garden, a layer of grass clippings between plants stops the soil drying out (and eventually feeds the soil biology).

Drippers, soaker hoses, or trickle irrigation are more efficient than sprinklers.

You can also use buried olla (pronounced ‘oi ya’) pots. They’re made of unglazed terracotta, so water slowly oozes out the sides, moistening the soil. Another option is to build a wicking garden.

MOWING

I find mowing lawns a waste of time. Longer grass is healthier (kikuyu excepted), more drought-resistant, and less prone to weed infestation. If you let it grow in spring to flower and set seed, it’s a great feast for beneficial insects and birds.

For some people, mowing creates a sense of achievement but consider at least mowing higher and less often. Perhaps leave swathes of meadow from spring to autumn and mow patterns and paths in it instead. Or graze it.

SPRAYING

I used to be so anti the use of glyphosate, people thought I was extremist. So I did some research into it.

I now recommend it as the most practical and efficient option to keep a driveway clear of weeds, so long as it’s:

• used correctly;

• kept well away from food-growing areas.

I’ve tried alternatives, including teams of weeding wwoofers. The only option I haven’t tried is a flame weeder.

I could concrete the drive, and I will if I ever win Lotto. Until then, I save time and effort by carefully spraying the compacted gravel of the driveway at certain times of the year. No roots or soil biology relating to my food-productive plants will ever grow there.

I also paint it on the cambium layer on stumps of weed trees. You can cover a stump with a huge pile of mulch and ‘cook’ it to death. But if that’s not practical, you face years of cutting back regrowth unless you paint glyphosate on the stumps.

I am not advocating the indiscriminate application of chemicals. I don’t use it near food areas. However, I also support the judicious use of a tool that makes life easier.

10 TIPS TO SAVE YOU TIME AND EFFORT

1. Deal with weeds when they’re small

Pulling out a weed before it flowers and spreads seeds will save you the hassle of trying to control thousands more for years to come. The seeds of some species can remain viable in the soil for up to 50 years.

Pull out ragwort and top paddocks where there’s young gorse plants. It’s vastly more effective if you do it before the plants form seeds.

It also saves you a lot of time. It’s very quick to pull out a little weed and leave it upside down on a garden bed for the worms to eat. It’s much faster than pulling out a big weed, shaking the soil out of its roots, carting it over to the compost pile, stacking it, turning it, and waiting for it to decompose.

Hoe or poke in the little weeds every week, cover them with mulch, and let them decompose.

2. Know your weeds

You want to spot and stop an invasive weed when there’s just one. Dig out all the roots.

3. Prune

Cut off diseased growth as soon as you notice it. Cut back or rub off watershoots while they’re small, usually in spring.

3. Feed your hive

You want to do this six weeks before your local food supply flush – bees will build up numbers in time to take maximum advantage of the flush.

4. Ring calves early

Do it while they’re still suckling on their mother. It saves you both so much stress.

5. Plant strategically

Leaving plants waiting too long or planting before the soil is warm enough puts them under stress, making them more susceptible to disease and reducing survival and production rates.

6. Tidy and mulch the orchard in Novembe

Any earlier and weeds will regrow. Any later and the soil dries out too much.

7. Book homekill mid-year for December

Kill beasts for the freezer in December. They’ll be a good size after the spring flush, you get great meat for your summer barbecues, and it takes the pressure off pasture before dry summer weather slows grass growth.

8. Use organic mulch

I call this in-situ composting. It’s amazing how a knee-high pile of weeds, left in the garden and covered in woodchips in autumn, will disappear by spring. You’re simultaneously insulating and feeding the soil food web and readying your garden for planting.

9. Winter work

Plant trees after the soil has been moistened by the first of the winter rains. The retained warmth in the soil and new moisture will encourage roots to establish, providing nourishment through spring. They’ll be healthier, more resistant to drought, and more likely to survive.

10. Stop and savour

Amongst all this efficiency, don’t forget the most important task of leaning on the gate and watching the grass grow. Is that animal content? Which type of grass is it eating? Which tree is blossoming? Which insects are feasting on the flowers? What has grown since last time you looked

What hasn’t? Where is the shade falling? Can you hear frogs croaking? Stop and savour the wonder of your world.

Sheryn’s DIY wicking garden bin

Wicking gardens have a water reservoir underneath to emulate the water table and rely on the ‘wicking’ effect of the earth and roots to draw water up to the plant. They’re very water and time-efficient, and plants thrive with consistent moisture.

MATERIALS

– container with waterproof sides

Weedmat over the end so water seeps out and stones can’t get in.

This could be a large pot or a plastic-lined raised garden – I cut up a 1000 litre bulk container (known as an IBC);

• 300-400mm of good topsoil;

• draincoil going into the water reservoir;

• indicator to show water level (optional);

• porous rocks and sand;

• divots in the stones, to create ‘wicks’ of soil – don’t use weed mat or any kind of barrier to separate the soil from the stones.

• water overflow hole.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.