8 reasons why you should plant a hedgerow

A hedgerow is an old-fashioned way to feed yourself and your livestock, and create valuable habitat.

Words & images: Rebecca Stewart

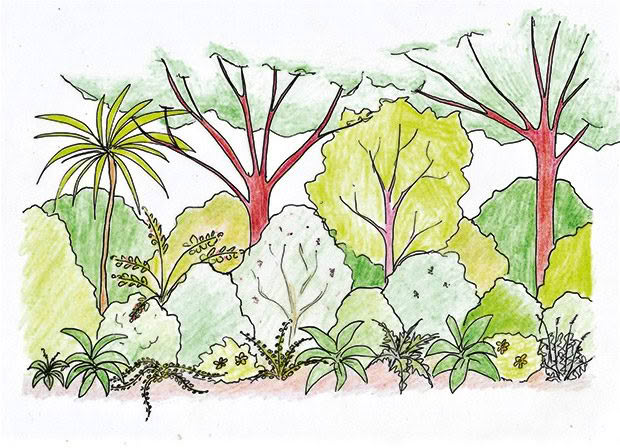

A hedgerow is a forager’s paradise. A place to gather everything: a handful of berries, a basket of greens, a feast of fruit within a tangle of trees, shrubs, climbers, brambles, and herbs. They’re also fabulous habitats for insects and wildlife to flourish and provide shelter and privacy.

New Zealand blocks and farms mostly have shelterbelts and hedges along roadsides and down fence lines, a single, uniform line of one species for shelter or privacy.

Hedgerows are wider and include a far more diverse blend of plants, such as:

■ fruit and nut trees;

■ berries;

■ flowers;

■ medicinal and edible herbs;

■ pasture species;

■ fodder trees for livestock;

■ trees for firewood, crafts, and timber.

Trees within a hedgerow are often coppiced or pollarded to provide firewood and fodder, then left to regenerate.

A hedgerow is also a haven for stock and wildlife. Animals can use it as shelter from the wind, shade from the hot summer sun, and as a food source. Birds and insects live and feed amongst clusters of plants.

Hedgerows in history

It might seem chaotic and messy to some, but a good hedgerow is an abundant, naturalised food and habitat resource. Farmers have used them as fences and food for thousands of years.

In Europe, traditional hedgerows often consisted of prickly stands of blackthorn, hawthorn, and barberry, planted for their berries and as a natural livestock barrier. Since fencing and boundaries were modernised, today’s hedgerows use less thorny plants.

In the UK, hedgerows lost to pasture and developments in the last few hundred years are now being restored to bring back diversity and wildlife corridors.

Hedgerow basics

A hedgerow is a sustainable way to maximize the use of your land. They’re long and narrow, creating a productive vertical space.

All the plants within a hedgerow should have at least one reason, but ideally multiple reasons for being there.

Traditionally, a hedgerow provided food, medicine, wood, fodder – feed that is harvested and taken to animals – and forage, where stock can walk up to the hedgerow and browse on its outer edges.

Modern hedgerows include nitrogen-fixing, mineral-accumulating, and soil-enhancing plants to help support the nutrition and growth of productive plants and trees.

However, you can also think about its appearance and include beautiful specimens. A hedgerow can be functional and look good too.

Where’s the best spot on your block

Hedgerows were traditionally used as fences, marking the outline of a paddock. While it’s practical to plant them along an established fenceline, there are other options.

First, consider the soil, rainfall (or lack thereof), wind, temperature, and angle to the sun, which will impact your choice of plants.

You can create micro-climates to support frost-tender plants, shade-loving, and cool climate plants.

A well-placed hedgerow can have dramatic effects on a landscape, reducing the land’s vulnerability to extreme weather such as drought or heavy rainfall, by:

■ providing shelter for exposed or flat, open areas;

■ preventing wind erosion and moisture evaporation of soil;

■ mitigating erosion and runoff.

If you plant a hedgerow along the contours of a clay hillside, following the land’s natural curves across a slope, it will catch rainwater and nutrients that would typically tumble down into waterways. A thick hedgerow will ‘catch’ the water and hold it in its root system.

Hedgerows planted in riparian areas can significantly reduce runoff into waterways, lessening flooding downstream. It also reduces the amount of pollutants and sediment that reach the waterways, acting as a physical barrier.

When to plant

Planting is best done from late autumn through to early spring to allow plants to establish their root systems before dry periods in summer. There’s less need for watering – unless it’s a particularly dry winter – as the soil is moist, helpful for root development.

Bare rooted plants are available from July to August and are an affordable way to purchase deciduous trees and shrubs.

Poplar and willows are also available as poles. You can then easily propagate more each year, coppicing growth to create your own pole resource.

Another economical source is plug or root trainer-grown plants from bulk supply nurseries.

However, many plants suitable for hedgerows are often easily grown from cuttings or seeds at a very low cost if you plan and propagate them ahead of time.

NATIVES

■ Options: pittosporum, corokia, coprosma, akeake, kapuka, harakeke/flax, toetoe, tī kōuka/cabbage tree, five finger, seven finger, karo, kohuhu, lemonwood, griselinia, hebe, mānuka, māhoe, horoeka/lancewood, houhere/lacebark, kōtukutuku/tree fuchsia, creeping fuchsia, koromiko, kawakawa, horopito, kumarahou, rengarenga, NZ spinach

Many native plants are suitable for hedgerows. There’s the usual hedge suspects such as griselinia, great for filling space, and livestock safe. Māhoe, kōtukutuku, tī kōuka, and mānuka provide height, but are also easy to manage.

Kakabeak, kowhai, and tutu fix nitrogen, but kowhai and tutu are toxic to stock. If you’re going to allow animals to browse, you could plant non-native soil-improving plants such as comfrey and other deep-rooted herbs instead.

Toetoe and harakeke spread outwards, fill empty spaces, prevent weeds, and can be browsed by livestock.

Koromiko is a multipurpose shrub that flowers through into autumn when there’s less bee food around and is also medicinal and good fodder. Other medicinal natives include kawakawa, horopito, houhere, and kumarahou.

Lower growing plants could include rengarenga, a lily with edible roots, prostrate coprosma and creeping fuchsia for edible berries, and NZ spinach for its edible leaves.

FOOD

■ Options: fruit trees, hazel, feijoa, currants, blueberries, gooseberries, berry brambles, grape, kiwifruit, globe artichokes, Jerusalem artichokes, rhubarb, climbing beans, herbs including fennel, rosemary, lavender, thyme, tansy, alexanders, parsley, chives, comfrey etc, perennial vegetables

Fruit trees do well in a hedgerow. It’s a good place to use up any peach, plum, or apple seedlings that pop up. It extends your orchard and acts as a buffer, so birds stop there to eat excess fruit.

Two possible exceptions are apricots and avocados, both toxic to stock.

Feijoa provide a dense evergreen barrier, flowers and fruit. Hazels have a lighter, deciduous canopy and delicious nuts for people and pigs. Persimmons are also excellent pig food.

Two traditional plants are elder for their flowers and berries and roses for their flowers and rosehips.

Most berry species originate from forest environments where they grow on the edges of tree lines or in clearings. They prefer cool root areas and should thrive as long as they receive adequate moisture. Currants and blueberries are easiest to harvest; gooseberry and worcesterberry are very thorny.

Bramble berries can also be painful to include, so you could choose thornless varieties. Raspberries naturally have fewer thorns and work well too.

FODDER

■ Options: tree lucerne (tagasaste), Japanese fodder willow, mulberries, apple rose, hazel, feijoa, holm oak, copper beech (hedged), wattle (coppiced), sweet chestnut (coppiced), alder (black or Italian, coppiced), Jerusalem artichoke.

Fodder or browse plants are well worth considering if the hedgerow is beside or in a grazing field.

The most well-known species used in hedgerows is tree lucerne. It’s a fast-growing, high-quality stock food, flowers prolifically, providing good feed for bees, fixes nitrogen in the soil, and makes good firewood.

Mulberries are a much larger tree that produces high-quality leaf fodder and delicious edible berries in autumn. They can also be successfully coppiced.

The smaller willow species, such as basket and Japanese fodder willows, do well in wet areas. You can use larger willow and poplar species, but they must be regularly coppiced as they tend to grow very fast.

Nitrogen-fixing alders and acacia species support the surrounding plants and can also be coppiced.

If you’re going to coppice bigger trees for fodder, forage or firewood, return their leaf litter and smaller branches to the hedgerow as ramial or chop-and-drop mulch.

The plants down low

The plants at ground height can include annuals such as calendula, borage, mustards, lupins, peas, phacelia, violas, or any herb or flower that won’t compete with young shrubs.

In drier sites, woody herbs such as rosemary, lavender, and thyme are great understorey plants that provide food, medicine, and flowers for bees.

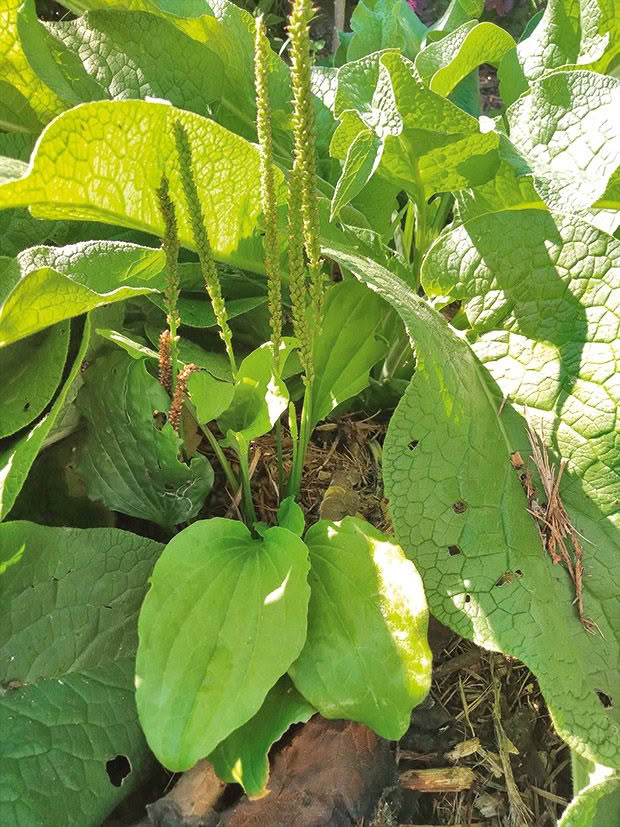

The deep roots of fennel, comfrey, yarrow, dandelion, and plantain bring up nutrients, then distribute them back to the soil as they die down.

Short-lived herbs such as calendula, borage, chamomile, parsley, and chives provide nutrients to the soil and food and habitat to beneficial insects.

However, these may not be feasible if you’re planting a large hedgerow on a block. Mulch and biodegradable plant protectors might be preferable, especially if you have rabbits and hares.

Perennial vegetables work well, including globe artichokes, Jerusalem artichokes, and alexanders, which provide food, flowers for bees, and mulch.

Rhubarb is a mineral accumulator but be aware its leaves can be toxic to livestock.

The legume family – peas, beans, vetches, clovers, lupins – provide nitrogen.

All these plants work together to feed and support the hedgerow and the health of the soil it grows in.

Hedgerows have so many benefits, and I believe they should be an integral part of our farming landscape. You can apply the principles I’ve outlined to other areas, such as gullies or an awkward corner in a paddock. If you’re planting a riparian area, why not add hedgerow plants, and make it even more helpful to your environment.

Rebecca’s tip: use mulch for weed control

Place a thick layer of mulch around plants for at least the first couple of years. It retains moisture in the soil, but more importantly, prevents weeds and grasses from suppressing the growth of trees and other plants.

I use wet cardboard covered with a 10cm deep mix of:

■ ramial mulch (freshly shredded leaves and branches);

■ aged woodchips and bark;

■ leaf litter;

■ grass clippings;

■ straw;

■ manure (around the base of plants).

Add more mulch each year until the hedgerow is fully established. Future mulch can come from trees and plants within the hedgerow itself, such as prunings and leaf litter.

Another option is a living ‘mulch’ of perennial plants such as comfrey, horseradish, rhubarb, strawberries, and clover.

Animals & hedgerows

You’ll need fencing to protect a hedgerow, either temporary or permanent, until the plants reach a size and density which can cope with being browsed. I recommend allowing for a minimum of 2m between the hedgerow and fencelines – more if you include larger trees – and electric wires.

If you live in an urban area, and a hedgerow will run along a boundary with your neighbour’s property, there may be height and overhang regulations. Check with your council before planting.

On rural properties, I recommend talking with neighbours about your plans. Ask if you can run a hot-wire on an outrigger on their side of the fence if they have large livestock such as cattle or horses.

If livestock will have access to browse along the edges of a hedgerow, ensure you don’t plant anything toxic.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.