Flowers, Ink, Pounamu, Stitches: How these four Kiwi women found their creative calling

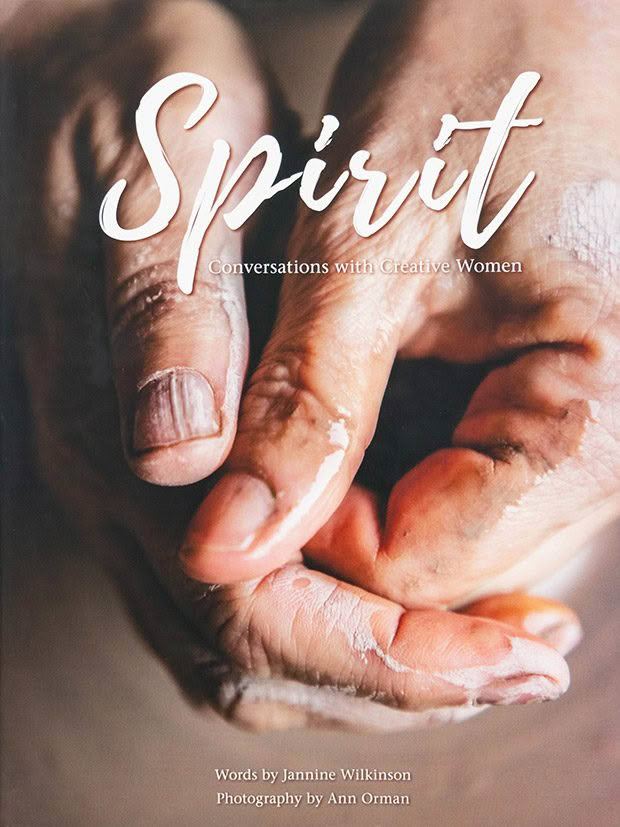

It took more than three years for this writer and photographer to compile stories about artistic women for their book, Spirit: Conversations with Creative Women. They share four inspiring journeys they captured along the way.

Words: Jannine Wilkinson Photos: Ann Orman

The women featured below, among 34 interviewed for the book, Spirit: Conversations with Creative Women, have opened their homes, workspaces and hearts and shared deeply intimate accounts of their personal challenges and determination to follow their instincts to create.

1. Gypsy West, Cromwell

Creative Florist | Romantic | Forager

Walking into the house of Gypsy West you would be forgiven for thinking you’ve just stepped into a beautiful flower-filled garden! A recent move to Cromwell has meant that she is currently working out of her kitchen, and her dining room, and the spare bedroom.

Oh, and the garden shed! She can’t wait for partner, Malcolm to get started on their new space where she will be able to spread out and organise her many, many buckets of flowers, dried foliage, feathers, vases, and all sorts of other interesting paraphernalia.

She’s always had a love of flowers, right back to her younger years gardening with her grandmother, aunt and mother in Tasmania (actually, just picking the flowers rather than any gardening). Having four distinct seasons meant there was always something new and exciting begging to be picked.

When creating Gypsy tends to select one piece of either a flower or foliage, and then works (in front of a mirror) to arrange around this piece. What is available at the time of the year may also dictate the outcome, and some dried components might be sprayed to achieve just the right colour. She dries all her own stock. Knowing when to stop is challenging – being careful not to swamp a small bride or make the bouquet too heavy to carry!

Moving to Cromwell means that Gypsy works out of her kitchen currently, but a soon-to-be-built new studio will mean she can properly unpack, to have the room to freely choose things on the fly, and to walk away from it all at the end of the day. She knows exactly what it is going to look like and how it will work.

There’s no downtime for Gypsy, being a mum, partner and dual business owner. There are lots of things she would still like to try, but her work is not work to her, it’s a total creative delight and one that she is inspired to enable others to share the joy.

2. Kate Hursthouse, Te Atatū Peninsula

Calligrapher | Mark Maker | Mum

Kate Hursthouse never thought that she would become involved in calligraphy or illustration when she studied architecture at university. She had very little interest in the design aspect and found herself spending more time on her presentations than anything else.

She eventually started working for an architect in Melbourne but the work was not what she thought it would be, finding herself working on toilets, electrical wiring, air conditioning, and plumbing – she hated it and it certainly was not at all creative. A worldwide crash also impacted her decision to get out of architecture, knowing that making any money in the industry at a time such as this would be difficult.

She decided to complete a one-year diploma in design school. It was the best decision she made, and she loved the learning of design and illustration. “I fell in love with drawing again.”

Kate feels strongly that changes in circumstances are there to feed change to your perspective, and to keep you learning and trying new paths. This was her first change in perspective. She felt that for her to be able to really do something creative meant she had to take a step back to be able to move forward and explore calligraphy in a deeper sense. So began years of learning and creating, starting with a simple night school class where she was taught the formal foundation of calligraphic styles.

It was a trip to Italy that really sealed Kate’s interest in calligraphy as an art form and her future as a full-time artist. A five-day experimental workshop based in a beautiful renaissance building, the home of calligrapher Monica Dengo, fed her creative side but more importantly showed her that it was ok to break the ‘rules’ of traditional calligraphy and challenge people’s views and traditions.

She’s dabbled with various styles over time, some of which are her favourite, some being more accepted versions of commercial calligraphy. This was a magic time for Kate, and one that ignited her love for the art form.

Calligraphy has a long history and is a beautiful and ancient art form that is becoming somewhat lost in the western world, but happily is still taught in schools in Japan and some other countries. This art form can be very rules-based and traditional and the recent breaking of these rules by creating new styles is not easily accepted by all. Japan has also played a big part in Kate’s love of lettering.

The learning and immersion into the art brought about another change in perspective for Kate. And so, without really any planning at all she started her own business. At the time she’d accept almost anything and everything, with a lot of guesswork around pricing. But it was all experience and the possibility of the work leading to something more. What it did teach her was the discipline of working with clients and budgets and working to deadlines and briefs, without losing sight of the value of her work.

Modern calligraphy allows you to push the boundaries on what has been traditionally acceptable. The letter A can be created in any form – it doesn’t have to conform to two slant lines with a crossbar. It can be anything. It is the architecture of calligraphy that is the passion. In the same way an architect will push the boundaries of building, Kate does with lettering and illustration.

So, what’s next for Kate? She’s getting back into the swing of things after having her baby boy Arlo and working through the next shift in perspective that having a baby brings with it. “Embrace the ebbs and flows – something will always happen or come up. Use lulls to do side projects and just keep chipping away. Life is fluid and is constantly changing. Keep open to this.”

3. Neke Moa, Ōtaki

Pounamu Carver | Teacher | Activist

When we spoke Neke Moa was living beachfront at Ōtaki in New Zealand and it was a wild, blustery day. Ōtaki Beach is a very giving area for Neke’s work, providing native wood that flows down from the Tararua Ranges ending up on the beachfront twisted or hollowed and worn smooth, or shells that sometimes feature in her work or as necklaces.

Even, at one point, a plastic chair leg that she has beautifully carved – you would swear it was bone. She finds tiny pieces of glass burnished smooth and fibres used for taura whiri (braided rope). These local resources are an important element and inspiration for her work and finding them is as exciting as creating them.

Her Māori heritage from her father’s side and her Scottish background from her mother are both strong connections for her. When she was little her grandmother taught her to forage on the seashore finding stones and shells that she would then make things with. She’s never stopped creating. Neke’s art comes from the ngākau (heart) and is fed by her culture, but she also recognises the importance of the formal training she completed.

It was her degree in Applied Arts from Whitireia Polytechnic, studying under Peter Deckers, that escalated her artistic skills. Neke learnt not only about the tools and techniques of jewellery making, but also how to talk and write in a way that enabled her message to be carried through her art, showing the meaning behind it.

Peter was an important influence in her learning, particularly due to his teaching style that allowed students to find their own way rather than imposing hard and fast techniques or ideas. Neke’s way was definitely one that was, and still is, uniquely her own, and despite some criticism, she feels strongly about following her own vision.

“I had to keep my identity and keep strong to myself – but be open to learn from others too.”

She spent three years learning Māori art at Te Wānanga-o-Raukawa. But it was more than learning the technique of weaving that she achieved. Being immersed in the language and stories of her people finally gave her a better understanding and connection to her Māori heritage. She learnt about her history and family from her auntie as a teenager and developed a beautiful relationship with her. She was told by one of the weaving tutors that maybe weaving wasn’t the medium for her as she regularly made work and used materials that were outside of the prescribed work.

Despite this, weaving is incorporated into her designs today and is seen as a connector of different elements, all of which can be traced back to its source. Every inanimate object has a genealogy or a beginning and is part of something that can always be traced back – everything is connected. She believes that you treat everything with respect as everything is also a part of you.

Working with pounamu (jade stone) is, for her, a treasured art, and a way to carry the stories of the past. The pieces are carefully chosen, and their creation emerges from the stone to become thoughtful items of adornment. It is the process of making and considering that keeps the piece evolving and flowing. Thoughts and ideas emerge as Neke creates. The final piece is the process or outcome of that thinking and storytelling.

After the spiritual work that goes into her pieces, rather than the sadness of letting the piece go there is an excitement that it’s moving on to its next life. She believes that everyone can wear pounamu. It connects us and protects us.

4. Liz Smith, Muriwai Beach

Stitchsmith | Designer

Growing up in New Zealand in the 1960s was a far cry from what it’s like now in the 2020s. Domestic life was simple, and where possible things were home-made. Liz Smith remembers her mother’s influence with stitching and her willingness to always try new things – she was a doer rather than a creative person.

Afternoons with her mother and two sisters were spent sewing and stitching, even making her own ball gowns (influenced by Jean Muir – look her up, she’s created some fabulous fashions) or each of them working a corner of a tablecloth, spending time together embroidering cross-stitch. The downside of this was suffering the ghastly home-knitted sweaters they were forced to wear.

Craft made a shift from a necessity to more of a hobby and is now morphing again, where it’s now once again fashionable to make from scratch. Knitting has exploded recently, and this has caused other crafts to also become fashionable again – and thankfully, patterns are keeping up with fashion trends.

For Liz, it was returning to New Zealand from overseas travels, and being laid-up for a couple of weeks suffering an inner-ear infection that was the catalyst for her to rediscover her creative side. She started on a stitching kit her sister had given her years ago and finished it in no time.

Once she started working again, it was in a stressful office environment with long hours, and her craftwork continued to be a restful escape to disconnect from work. At that time the availability of good designs was limited and a little predictable and she felt there was a gap she could fill by creating her own New Zealand themed designs.

Starting her own business with little knowledge of what this entailed meant many mistakes – in hindsight if she had known what was involved, she might not have even done it. But she persisted and continued to explore ideas of getting her designs on to canvas. She wasted a lot of time trying to source relevant people that could supply quality materials and the consistency of supply that she needed.

Liz uses a graphic designer to help bring her ideas to life and feels grateful that the company she uses is able to interpret her designs and get them on to paper. The next step of printing the design on to canvas was a challenge. Initially, there was only one machine in Auckland that could even attempt to do this, but she struggled with the stable flow of ink and the designs came out patchy. The process was right, but it just wasn’t the right printer. She eventually found someone that could produce the quality she needed – and she’s still with them today.

Her first designs were popular and, as she thought, filled a gap in the market. Being a somewhat shy person, she was way out of her comfort zone traipsing around the shops trying to sell, but the positive response from the stores and subsequent sales enabled her to take the next step of developing further kit designs. The designs have kept coming, and Liz has expanded into workshops that bring together women that have a similar desire to learn and create.

This is an extract from Spirit: Conversations with Creative Women. Written by Jannine Wilkinson, photography by Ann Orman. Book available online at thecreativecollectivespirit.co.nz or from select book stores around New Zealand.