Fern fever: Why Lynda Hallinan can’t give up on fussy ferns

A true Wardian case is sealed, maintaining humidity through a continual cycle of evaporation and condensation. But Lynda’s modern Mitre 10 version does a sterling job as a maternity ward for baby ferns, fogging up each night and clearing during the day.

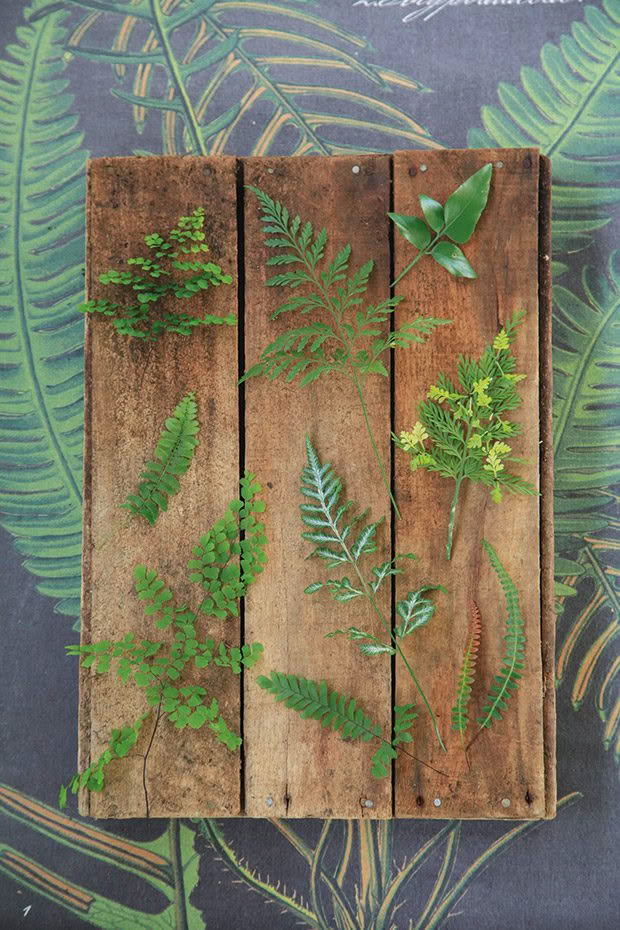

Lynda indulges her fever for ferns with a tabletop collection of covetable species.

Words: Lynda Hallinan Photos: Sally Tagg

I’ve been looking for the first signs of spring in all the wrong places. I’ve had my head in the clouds, shooing rosellas out of my ‘Shimidsu Sakura’ cherry trees lest these prettiest of pests strip all the blossom buds. Again. I’ve been patrolling our paddocks, perving on our pet sheep, quietly willing Marley and Lucy’s perky udders to swell. I do hope Boris the ram isn’t shooting blanks.

After my daffodils jumped the gun to bloom in June, I’m growing impatient for freesias and tulips. Still, the only evidence of an imminent equinoctial awakening is a smattering of strawberry blossoms and a weedy blanket of trigger-happy hairy bittercress (Cardamine hirsuta) firing seeds at my ankles.

Forget the traditional symbols of spring: the bluebell woods, baby birds and the idling hum of foraging bees. The real harbinger of a southern hemisphere spring must be the koru. From the tightly clasped pikopiko of hen and chicken ferns (Asplenium bulbiferum) to the clenched fists of whiskery whekī (Cyathea medullaris), the coiling koru is integral to Māori kōwhaiwhai, a spiral of perpetual motion, an iconic motif of creation and renewal.

Since the 1850s, ferns have been printed and pressed to make patterns on everything from cushions to curtains. Dip a frond in paint, use as a stencil, or press into handmade pottery. The unusual variegated frond (above, centre) belongs to the silver lace fern, Pteris ensiformis ‘Evergemiensis’.

I adore ferns. I fancy a full-blown sunken fernery, layered from sky to soil with ferns and mosses, but for now, I’m content to cosset a potted fern collection in the sunny covered verandah of our stable block.

Collecting ferns holds an appeal as primal as the seven deadly sins, satisfying a checklist from lust to pride, but it also feels like The Hunger Games. Who will live, and who will die? The odds are stacked in the compost heap’s favour.

Most people have heard of Tulip Mania, the original Dutch get-rich-quick scheme of the 1630s, in which fortunes were made and lost in a speculative bulb-trading bubble. Less well known is that, in the mid-1800s, the English developed an almost cult-like fascination with ferns.

Ferns do best in moist conditions such as bathrooms or the sills of south-facing windows that weep on winter nights. Lynda has lost count of the number of Boston ferns and maidenhairs she has knocked off in her sunny stable block, but others, such as the giant sword fern, Nephrolepsis biserrata ’Macho’, seen here at the front, have flourished. Lynda holds a ‘Silver Lady’ blechnum fern in a pot her mother’s boss made as a maternity-leave gift in the 1970s. The Green Life Panel wallpaper mural on Lynda’s covered stable block verandah is from the Caselio Sunny Day Wallpaper Collection.

This fashion for fern hunting so consumed well-to-do Victorian women that, in 1855, Charles Darwin’s friend Charles Kingsley gave their obsession a name: pteridomania. In his book Glaucus, or, The Wonders of The Shore, he declared “the prevailing pteridomania, with its wrangling over unpronounceable names”, to be a good distraction for daughters preoccupied with novels, gossip, crochet and embroidery.”

Pteridomania was only made possible by an accidental invention by London doctor Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward in 1829. Having popped a hawkmoth cocoon and a handful of soil into an airtight glass jar, he was stunned to find ferns and grasses sprouting inside the fogged up jar a few weeks later. He sketched up manufacturing plans for a scaled-up version, and the self-contained glass Wardian case — the precursor to the trendy terrarium — was born.

Until then, Victorian plant hunters had been having a devil of a time trying to ship exotics to England. There was a mistaken belief that plants needed fresh air to survive the long sea voyages, so they were generally transported on the upper decks, where they shriveled in the sun or were burned by salt spray if ship rats didn’t eat them. Ferns had no hope.

Offering a mobile high-humidity microclimate, as well as being a lovely display box for ferns, Wardian cases became a vital tool of imperialism. They were used to smuggle tea out of China, rubber plants from Brazil, and Peruvian cinchona seedlings, the bark of which was distilled to make the anti-malarial drug, quinine.

The hen-and-chickens fern, Asplenium bulbiferum, so-named because it produces baby bulbils on mature fronds. These can be picked off and potted up.

By the mid-1870s, colonial gardeners with dosh were exhibiting their posh Wardian cases at horticultural society shows across New Zealand; the prize money for a fancy box of ferns was more than twice that offered for the finest potatoes or fuchsias. Wardian cases also brought white mulberries, olive saplings and the phylloxera aphid Down Under. A plague upon commercial vineyards, the pest hitchhiked here in 1881 from England in a Wardian case of “sickly, weak, miserable vines”.

In 1893, the renowned English nurseryman James H. Veitch filled 12 large Wardian cases with New Zealand natives sourced from a Dunedin nursery. He snapped up astelias, cabbage trees, celmisias, pittosporums, ranunculi, rata, ribbonwood and veronicas, plus three ferns never before seen in England: the umbrella fern Gleichenia cunninghamii, the walking stick fern, Lomaria fraseri, and the hardy alpine shield fern, Aspidium cystostegia.

Veitch’s shopping trip made headlines in the Christchurch Star. “The gentleman in question has, or has seen, all the best plants in the world. It is no mean praise to our local and New Zealand plants that he has made such extensive purchases.” You’d be hard-pressed to find any of those ferns for sale in local plant nurseries now that plundering them from the wild is forbidden.

The common delta maidenhair, Adiantum cuneatum, in the pale green pot, seems to have a death wish compared with its easy-going New Zealand native doppelganger, Adiantum aethiopicum (in the terracotta pot). “It’s tough as boots,” says Terry Hatch. Lynda has a naturalized patch of it in her garden that has survived winter frosts, summer droughts and repeated attempts at eviction by her free-range chickens.

Though when I walk my dogs along the Mangatāwhiri ridges of the Hunua Ranges, I can admire the same gleichenia (now renamed Sticherus cunninghamii). I grow its baby sister, Sticherus flabellatus, a gift from Terry Hatch at Joy Plants in nearby Pukekohe.

A 1951 survey of the Hunua Ranges chalked up 45 fern species, almost a quarter of our national total, with names that read like a hocus-pocus magic spell: Cyclophorus serpens, Hymenophyllum sanguinolentum, Notogrammitis billardierei, Polystichum adiantiforme, Pteridium esculentum, Tmesipteris stigmatophilia and so on.

Although just under half of our native ferns, including the silver fern (Cyathea dealbata), grow nowhere else globally, about the same number are also indigenous to Australia. A quarter are found around the Pacific, and a dozen or so have genetic twins in South America and Africa. With windblown spores, they have wanderlust as well as a genetic predisposition to turning up their toes with no warning.

Lynda repurposed a French vintage yoghurt-maker from All Things French in Wānaka as a tray for tiny ferns.

Why are ferns such fusspots? Perhaps they’re not; maybe they’re simply pining for the party vibe of the forest floor? “If plants and trees can communicate via their root system, do they get lonely in pots?” posed the New Scientist in its Last Words column.

Yes, replied Auckland University of Technology lecturer Sebastian Leuzinger, who has discovered leafless zombie kauri stumps in Waitakere forests that are being kept alive by neighbouring trees sharing resources through their roots. “Plants will definitely experience something like being ‘lonely’ in pots because they miss out on underground connections. Most plants form symbioses with fungi underground, via their roots.”

In a forest community, they can exchange carbon, nutrients and water, and send chemical signals and plant hormones, “something that is definitely out of reach for a solitary plant in a pot”. The thought fills me with shame. Instead of killing my houseplants with kindness, could solitary isolation be a trigger for horticultural hari-kari? I’ll have to buy some much bigger pots and tuck all my ferns in together.

FRONDS WITH BENEFITS: GROW YOUR OWN FERNS

Find it hard to keep ferns alive? You’re in good company. At Joy Plants in Pukekohe, famed nurseryman Terry Hatch admits he has his moments too, despite 70 years of experience propagating all kinds of plants.

Terry’s most coveted native fern is the prince of wales feathers fern or heruheru (Todea superba, a.k.a. Leptopteris superba). “It’s a beautiful thing, and there are masses of it in the Tongariro National Park, but I’ve not had any luck with it.”

The shiny fan fern, Sticherus flabellatus, a rare Kiwi native that Australians can also claim as one of their own. As it grows, it sends out new fronds from the end of its tips.

Aside from the usual suspects, most native fern species are never offered for sale in garden centres, not because there’s no demand for them, but because very few nurseries can supply enough of them to make it worthwhile.

The wee sporelings aren’t difficult to raise from spores, but they’re interminably slow to grow, taking years to reach a saleable size. A punnet of pansies takes two months from seed to sale, Terry sighs, whereas most ferns take at least two or three years. “They grow so slow; no one can grow enough of them.”

In the past, nurserymen would head deep into the bush, dig up plants and bundle them up in moss to keep them moist until they could be potted up. Ponga trunks were top and tailed and hauled out of forests to build whares, fences and retaining walls. They often resprouted, only to find themselves in full sun instead of the cool shade they were previously accustomed to.

Boston ferns are beautiful in hanging baskets, if their fountain-like fronds don’t dry up.

If you have access to a private bush block where you are allowed to eco-source ferns, don’t bother trying to uproot mature specimens, Terry advises. They invariably wither and die. Take cuttings instead, pulling or cutting fronds off at the base.

“Cut off the base, chop them into 5cm pieces and poke them into a tray of bark or sand — it’s important there’s no fertiliser. Water well and put a plastic bag over the top, and leave them for a month. It’s surprising how many will quickly make roots.

“Oddly, we’ve found that if you can get a cutting of a rare fern to grow, and then you take cuttings from the second generation, it gets easier and easier. They’re like elephants. You can gradually make them tame.”

MORE HERE

Lynda Hallinan’s Blog: You say tomato, I say make ‘mine a double’

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.