A mid-age bike-lover finds meaning in a Communist-era motorcycle

Originally designed in late-1950s communist Czechoslovakia, the Czeta was rebranded to NZeta when it reached Aotearoa. One, now meticulously restored, helped this bike-lover through a mid-life crisis.

Words: Chris van Ryn Photos: Rouan Lucas van Ryn

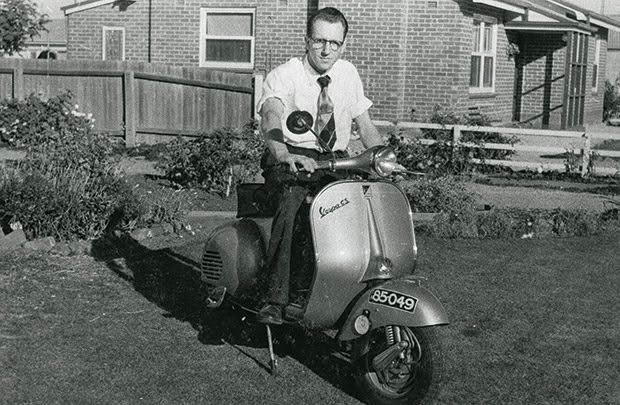

At the end of World War II, an uncle of mine went to Australia from Holland. When I was a kid, he regaled me with stories of riding thousands of kilometres through the parched outback on his Vespa. Long roads, hot sun, not a soul in sight.

He packed everything he owned into a top box, strapped to a carrier, together with a jerry can of fuel. At night, he would park under the stars, the moonlight casting a Vespa-shaped shadow onto the ground where he slept. If he got a flatty, he’d flip the scooter over and put on the spare. It took minutes.

Chris’ uncle, Henk van Hooijdonk.

For the better part of two years, his scooter tracks crisscrossed the outback. Maybe he was getting the war out of his system? Those stories shaped my imagination and desires. So when I was a teen, my first motorized vehicle was a scooter.

It symbolized independence and freedom; it had style — a way to stand out from the crowd. The vehicle had excellent provenance. The Americans parachuted a small scooter behind enemy lines in World War II and Vespa (Italian for “wasp”) modeled its now-famous two-wheeler on it.

The scooter gave Third World countries such as Indonesia and Brazil an economical form of transport. India shipped an entire Vespa factory from Italy, re-assembled it, and manufactured a Vespa-branded Bajaj. It putters around today carrying towering loads, along with the whole family. And the Vespa gave Audrey Hepburn a ride behind Gregory Peck in Roman Holiday.

In the 1970s, I would scooter around Auckland in lizard winklepickers and a long Russian overcoat. I was a decade out, a throwback to the 1960s scooter sub-culture called The Mods. Then came work and family, and 30 years sped by.

The crisis of the middle years descended. I was travel writing, satisfying my globe-wandering urge, but I had lost direction. When I saw a clapped-out scooter on Trade Me, with an odd, dominant proboscis ending in a single car-headlight, I felt my pulse quicken.

This wasn’t just a scooter, it was my uncle and his ride to recovery. And in some way, it promised my own. I thought, ‘I’ll ship it to Auckland and nurse it back to health, nut by nut, panel by panel. Then I’ll ride my way through the midlife blues.’

Only later did I realize I didn’t have a garage, tools, or know-how to pull the thing apart and rebuild it. Not nut by nut. Not panel by panel. The fantasy collapsed. What on earth was I thinking? The scooter had an oval badge on it. I looked closer.

It was an NZeta. I was astonished to find I’d purchased a genuine piece of Kiwiana. In production from 1957 to 1960, it remains New Zealand’s only manufactured scooter.

The NZeta was a carbon copy of a Czeta from communist Czechoslovakia, where it was manufactured during the post-war years. In a way that’s hard to pinpoint, it looks communist. In 1957, Aucklander Laurie Somers started importing and assembling the Czeta, making components in Aotearoa and rebranding it the NZeta. It cruised the streets for three years.

Amazingly, I was able to source parts from the Czech Republic. I purchased new exhausts, footrest rubbers, mud flaps, and indicators. A local mechanic removed the NZeta’s 175cc Jawa engine and, over the next five years, it traveled up and down the country in pursuit of someone who could rebuild it from scratch. It went from Christchurch to Auckland to Dunedin; up to Whāngārei and down to Pukekohe and then to Manukau.

The engine was fitted with new bearings, seals, piston rings, and chain. The barrel was re-bored. The clutch was renewed. The gears adjusted. Wheels were refitted with high-tension bolts. And the seat was remade in leather — honey brown, with an orange-peel texture.

I bought the hide myself and delivered it to the upholsterer with a pattern I drew on the computer. I meticulously studied images of original Czetas and painted my NZeta in two-tone — red and white. But every time the scooter came home, it was never quite roadworthy. I felt ready to give up. This restoration dream is over, I thought.

Then I had a chance encounter with someone at a heritage luncheon that changed everything. The guy next to me, Ken Woof, owner of the heritage home, Whare Tāne in Mt Eden, told me of his hobby of restoring classic cars. He put me in touch with Ryan from Mac’s Garage in Glenfield. I had the scooter delivered there.

My brief was simple: get this thing roadworthy. A month went by. Lockdown came and went. Another month. Then two more. And then I received an email — it’s done.

Ryan had it purring. “It’s a great ride,” he said. “Solid as a brick shithouse.” Getting the NZeta registered caused further consternation. There were no previously known New Zealand owners.

Working with the Vintage Car Club, I filled in forms and signed a certificate of compliance. The compliance centre checked and recorded the chassis number. I filled in an NZTA alternative documents form and sent the package to New Plymouth for sign-off. It took 10 years to restore the NZeta. My mid-life moment has passed. But it’s not too late. I plan to ride the length of the country looking for the post-Covid-19 New Zealand spirit.

I’ll park in some coastal town and fossick for stories before winding my way down the rugged west coast. And at the end of each day, I’ll hunker down beside the shadow of the NZeta, cast by a full moon, and look at the stars. Then again, maybe I’ll stop at a motel.

RESTORATION OF A CLASSIC

Outsourcing the restoration of any classic vehicle is not for the fainthearted — or those without some extra cash. Finding the right people is paramount. An excellent place to start is the VCC (Vintage Car Club of New Zealand).

Despite the name, members are interested in two-wheelers as well. Many VCC members are professional restorers. Visit and talk with the mechanics and make sure the scope of work is bedded down. Depending on the level of restoration, getting a quote can be near impossible as there are too many unknowns.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.