Sarah Hopkinson transforms the front lawn of her 800sqm section into a productive vegetable garden

The Hopkinsons — Albert (8), Marcus, Fred (5) and Sarah — at home in Raumati, Wellington.

Sarah Hopkinson’s personal and professional passions come together in a sandy section she’s transformed into a productive garden.

Words: Lee-Anne Duncan Photos: Nicola Edmonds

Sarah Hopkinson’s house, a few blocks back from Raumati Beach, is easy to spot. A pile of foraged mulch, bountiful vegetable beds, laden fruit trees, an abundance of bees and the gentle cluck of chickens give it away.

She has lived here with husband Marcus and their sons Albert (8) and Fred (5), for three years and the 800-square-metre section provides much of their food. Sarah, an environmental educational consultant, also hopes it does a tiny bit to build a better future.

Her connection to nature started in Taranaki with parents who grew vegetables and regularly took their kids on bushwalks. But that childhood experience had little relevance until Albert was born; he had a congenital heart defect.

“Then I knew I wanted to grow our own food – to produce healthy, organic food for my kids from the land we were occupying and live more sustainably.”

Sarah, who trained as a teacher, started promoting sustainability more than a decade ago with The Big Shwop – organized events where people swap clothes. She also designed the Pūtātara programme for schools, a resource that uses te ao Māori concepts to “incorporate sustainability and global citizenship across the curriculum” and is also writing the curriculum for New Zealand’s first Green School.

“I feel like my past life, professional life and my life story are all connecting.”

But Sarah has a problem with the word “sustainability”. “It imagines we can ‘sustain’ what we already have, but that means continuing to use really broken systems,” she says. She prefers regeneration and imagining what it means to live in connection with the Earth.

“With ‘sustainability’ we talk about ‘innovation’ and ‘green tech’, and that’s connected to it, but we’ve forgotten that we’re part of the planet. I hope schools that pick up Pūtātara, and places like the Green School, will reconnect the younger generation.”

Sarah also hopes that as the boys watch and help in the garden, they’ll soak up her philosophies. When the family bought the steep property, there were a few established fruit trees and an asparagus bed. With help from permaculture consultant Kath Irvine at Edible Backyard, they have since added vegetable beds and more fruit trees, espaliered to encourage fruiting. There’s also a “lizard-friendly garden” with native muehlenbeckia, tussock, astelia, broom and rock daisies.

Sarah loves the view from the top of her “lizard-friendly” garden, down to the raised vegetable beds and road. “Seeing our land growing our food rather than grass is deeply satisfying. I’m constantly blown away by the intelligence of the planet. There is so much more to gain from growing vegetables than you might initially think.”

While it was a sacrifice to replace the front lawn with vegetables, it was a visible way of spreading the productive-gardening gospel to neighbours and passers-by. It’s also become a gnome-retirement centre, with two gnomes dropped off anonymously.

The family still buys potatoes, onions, carrots and some fruit from local markets (in compostable brown paper bags) but most meals are based on their home-grown bounty. “At the end of winter, we’re happy to see the last of the cabbages but so excited to have tomatoes again. I get much more joy from the rhythms of the land than from buying winter tomatoes.”

Sarah also gets joy from letting nature do its thing. A self-seeded mini food forest contains a veritable salad of rocket, edible calendula, dill, mint, coriander, lettuce and even potatoes. “I love being a bit chaotic and seeing what comes up.”

More structured is her seedling nursery; Sarah raises about 90 per cent of her own seedlings. Grown from Setha’s Seeds, many are heirloom New Zealand varieties that were brought here from all over the world. Favourites include an Amish melon and a Japanese eggplant that traces its lineage back to 1855.

“Lately I’ve been thinking about not only what it means to be a great person or parent, but a great ancestor to our children’s children’s children. What world are we setting up for them?” says Sarah. “The people who developed the seeds probably never imagined that, 100 years later, I’d be connecting with their story.”

To close the loop on vegetable waste, Sarah’s added six gorgeously glossy hens (four she raised from eggs), a worm farm and compost bins. The glistening worms munch through some of the kitchen waste while the hens eat scraps, and pick over and poo on garden waste thrown into their enclosure until it becomes compost.

Sarah runs two compost bins, which take green waste, ash, brown paper and food scraps the worms won’t eat. She plunges her hands into the aerobically decaying matter, turning it over as she inhales deeply. “If it’s good, it smells like the forest floor.”

When it’s ready – in six months or so – that fertilizer is dug into the garden and mulch spread over. Sarah mulches three times a year using family-foraged seagrass. “Mulching means I barely need to weed.”

While gardening is still a popular hobby, for Sarah, it’s so much more. “By getting my hands in the soil and growing vegetables, I’m lessening air miles, plastic waste and pesticide use, and saving money. So many issues are addressed at once.”

Away from the garden, the family does its best to reduce its carbon footprint. They wear mostly secondhand clothes or choose ethical fashion labels, primarily Kowtow for Sarah and Cotton On or Hoopla Kids for the boys.

Sarah’s approach is to consider each problem individually. Maybe take reusable containers to a local provider or source one that’s not plastic wrapped? Fred and Albie like cured meat, so Sarah found a local butcher who wraps salami in paper.

For coffee or beer, they take along their own Tupperware containers and flagons. They’ve also signed up to a dry food co-op, so much of their store goods are bought in bulk and shared among 148 member families (see below). Their toilet paper is delivered in a cardboard box.

As a working mother of two, Sarah knows that, with more time, she could do more but believes that living “regeneratively” is about doing the best possible.

“We don’t need a few people to do zero waste perfectly; we need a lot of people to do zero waste imperfectly.

If everyone tried their hardest, we’d get a long way.” Follow Sarah Hopkinson on Instagram/thegreengardennz

SMALL GARDEN, BIG PANTRY

Think there’s not enough room to grow your own food? On her residential section, Sarah grows tomatoes, peas, lettuce, silverbeet, cavolo nero, asparagus, beans, edible flowers, broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, cucumbers, artichokes, courgettes, rock- and watermelons, pumpkins, chayote squash, chillis, capsicums, rhubarb, pears, guavas, strawberries, blackcurrants, blueberries, raspberries, plums, feijoas, figs, apples, cherries, limes, mandarins, tamarillos, bananas (barely), passionfruit, lemon verbena, parsley, chives, oregano, mint, vietnamese mint, sage, basil, rosemary and thyme.

DRY FOOD CO-OPS

Join (or start) a dry goods’ cooperative — a plastic-free and money-saving way to stock the pantry. Sarah and Marcus are part of the Kāpiti Organic Dry Foods Co-Op, which involves nearly 150 families. Organic food, including butter and cheese, is bought at wholesale prices or direct from the producers and delivered to a central point once a month.

Members pre-order their stores and come along with containers. “You also go on a roster for jobs like filling the orders or tidying up. It’s lovely for community connections,” says Sarah.

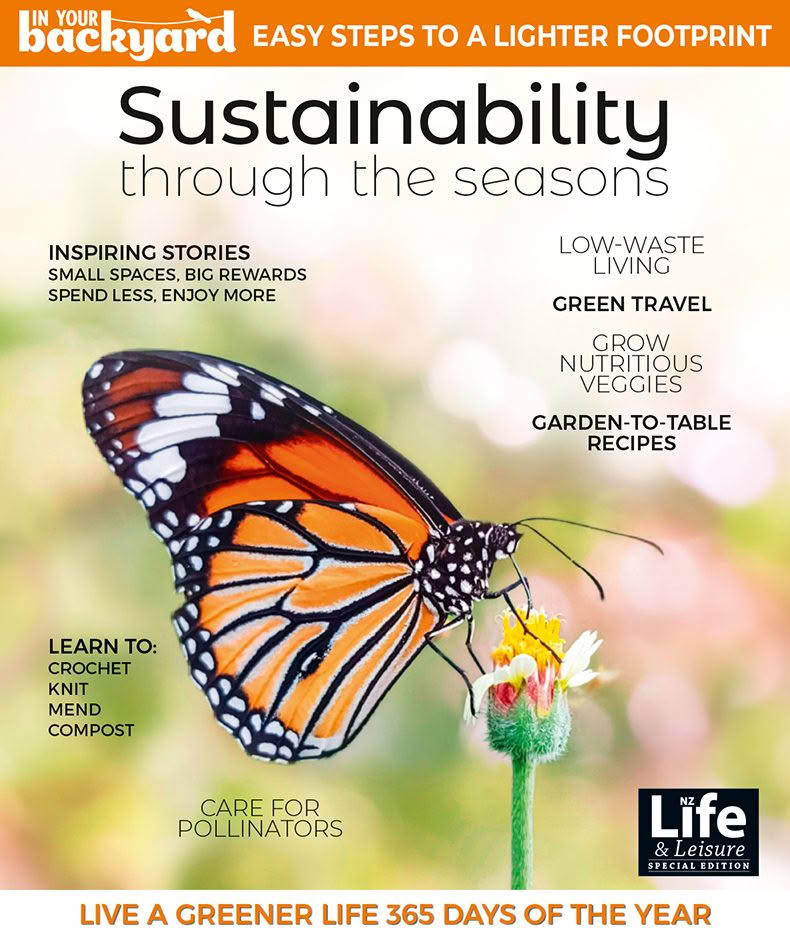

Read more stories like Sarah’s in our new annual, Sustainability Through the Seasons, on sale 30 March.