The outback, history and scenic views: The Wool Wagon Pathway certainly packs a punch in Western Australia

A straight line of dirt road brings visitors into the remote Kennedy Range National Park.

Australia’s iconic Wool Wagon Pathway — a 1100-kilometre route across the Western Australian outback – originally came into being thanks to profits made from wool. Sheep, however, are a rarity nowadays.

Words & photos: Don Fuchs

In 1894, the future of Pindar, 98 kilometres inland from the coastal city of Geraldton and 415 kilometres inland from Perth, shone brightly.

The railway had just arrived at nearby Mullewa (an already thriving West Australian town), and work was underway on 30 kilometres of further rail tracks stretching into the golden lands of the mid-western wool and cereal belt.

The railhead reached Pindar and up sprang a bustling township. Heavily laden, animal-drawn wagons lumbered into town daily heading for the railhead, their load destined for lucrative international markets.

Things were going well in the Australian wool industry; sheep numbers had already topped 106 million by 1892, and each year the wool clips edged higher (289,380 tonnes by 1892). The Murchison and Upper Gascoyne area of West Australia, inland from Pindar, was regarded as one of the finest wool-producing regions in the country, with bales often achieving record prices at London auctions.

The annual Polocrosse Carnival in Murchison is not just a sporting event but also a social one — players, supporters and spectators from hundreds of kilometres away gather for two days to watch, gossip, catch-up and laugh.

From the Federation-style veranda of a fine two-storey stone hostelry (built for Mr Emmet Gill and his wife), guests overlooked the unloading of wool wagons arriving in Pindar from the hinterland and its reloading onto rail wagons destined for the port at Freemantle.

The town rode the fortunes of the wool economy. There was the rural depression of the 1890s, a prolonged drought between 1895 and 1904 (in which sheep numbers declined by 50 per cent) and a boom in the late 1920s when sheep numbers again reached 100 million.

By 1937/38, the year’s clip was 440,000 tonnes, accounting for a healthy one-third of the country’s total export earnings (46.9 million pounds).

Up and down the industry soared and fell, with the most recent crash coming after the boom of the early 1980s when production reached one million tonnes and prices soared to $10 a kilogramme. And then came the great wool crash following the collapses of first the USSR wool market then the international share market.

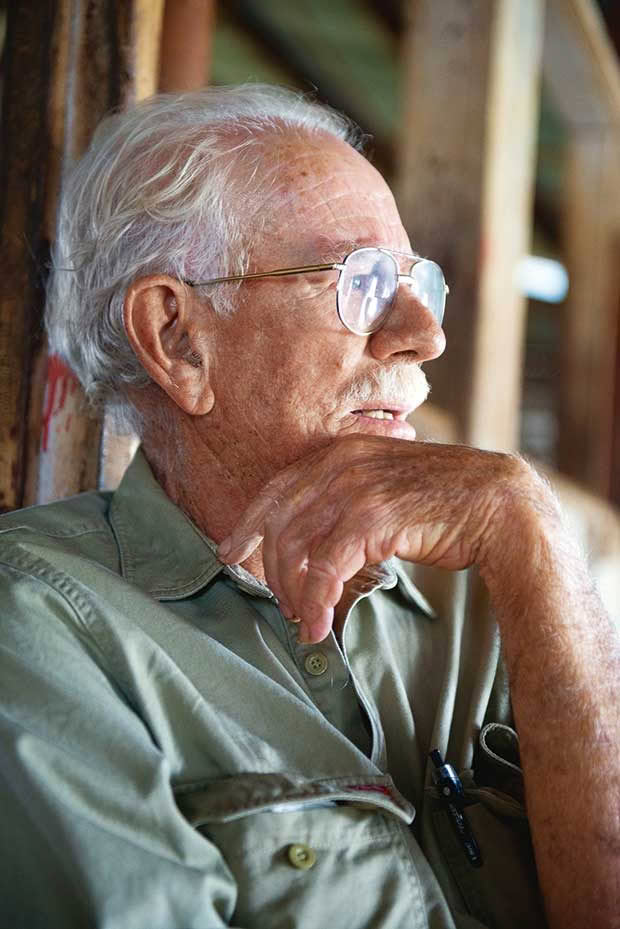

Farmer Frances Jones on Budara Rock. As far as her eyes can see is her land, which is going through an astonishing transformation — from serious degradation to a species-rich paradise.

Within a few years, there was an unsold stockpile of 4.7 million bales of Australian wool. The wool crash is estimated to have cost the Australian economy $20 billion in today’s terms — one of the country’s biggest economic disasters.

So, too, went Pindar’s fortunes. Its iconic pub still stands at the heart of things, but it’s a stretch to describe anything about the town today as bustling. Its population doesn’t quite reach three dozen, and it’s not a long drive to the end of the bitumen.

However, the dirt road stretching out from the town into flat land under enormous skies upon which the wool wagons once lumbered now attracts another sort of pioneer.

The soft sandstone in the aptly named Honeycomb Gorge within the Kennedy Range.

Heading into the outback for an epic journey of more than 1100 kilometres following the route of the old Wool Wagon Pathway (WWP) is not for the faint-hearted and requires something of the grit — and plenty of the forethought — of farmers of old.

Fortunately, the WWP is still populated, albeit sparsely, with hardy and entertaining souls whose work today is still mustering passers-by.

Sixty-three kilometres north of Pindar is Yuin Station, owned by Emma Foulkes-Taylor and her husband Rossco. Yuin was once ruled by sheep.

“This country was opened up in the mid-1860s with flocks from the coast — from Northampton — coming into beautiful saltbush flats on the Greenough River,” says Emma.

“In those early days, sheep being grazed along the coast suffered from a mineral deficiency that became known as ‘coastal deficiency’.

However, on the more varied diet of the inland conditions, they recovered quickly. Over time, water wells were dug, more sheep arrived and eventually Yuin Station was established in 1867.”

The Wool Wagon Pathway logo is an animal-drawn wool wagon.

The 130,000-hectare property was the earliest established in the region and the first with a shearing shed.

At one time, all the sheep from surrounding districts were shorn there, with shearing going, non-stop, for five months each year. Wagons, hauled by horse, donkey or camel teams then lumbered off to the Pindar railhead laden with 45 to 50 bales.

“Like most pastoralists, we’ve had to diversify dramatically to survive — to keep living here,” Emma says. By 2004, the family faced a serious situation: drought, diminishing returns and the possibility of a ban on mulesing (a controversial practice, banned in New Zealand, of cutting skin from around the sheep’s tail to restrict flystrike).

A family braves the 90-minute trek into Temple Gorge in the Kennedy Range National Park.

They switched breeds from wool-producing merinos to meat-producing dorpers and reduced their flock to just 1400.

Once, Yuin Station carried 25,000 sheep. But even this has not seen the end of its troubles. Now there is the issue of wild dogs, descendants of the European dogs released into the wild in the late 1700s. These feral dogs, different from dingoes, roam freely in large packs.

“We’ve built a dog-proof fence around half the property, and now we’re looking to restock,” says Emma. The decline of the wool industry and the changes it has forced on the stations is a frequent topic of conversation along the WWP.

Michael Foulkes-Taylor of Yuin Station can still remember that when he was a child, more than 5000 bales of wool went through nearby Pindar every year.

While Yuin Station has its money on meat sheep, the approach at Wooleen Station, 130 dusty kilometres north of Yuin, is very different.

In the heyday of the wool boom, Wooleen carried 30,000 merinos, but overgrazing caused significant land degradation. Frances Jones and David Pollock, who now run the 153,000-hectare pastoral lease of Wooleen Station, are trying a different approach.

“We believe that the land, not just from an environmental perspective but economically, is only producing a fraction of what it could.”

Sheep, like this meat-producing variety along the last kilometres to Exmouth, are now a rare sight along the Wool Wagon Pathway.

About 10 years ago, they decided to let the land recover. They de-stocked, and currently only about 100 head of cattle roam the vast station. Once the vegetation has improved, they plan to run cattle but in a sustainable way. To survive the interim years, they’ve banked their money on tourism.

On the way to Budara Rock, a massive granite outcrop with precariously balanced boulders on sloping granite slabs, Frances explains that Wooleen Station offers WWP travelers a range of options: rooms at the homestead, camping, walks, various drives, sunset tours, stargazing, picnic lunches and bird watching.

Just a short 36-kilometre hop from Wooleen Station is the tiny, usually peaceful outpost of Murchison. On this July weekend, however, it’s buzzing with the annual two-day Polocrosse Carnival.

Emma and Rossco Foulkes-Taylor, the current owners of Yuin Station.

Twelve teams from across the mid-west are here to compete. For 47-year-old Peter Sands Mahony, business is good this weekend. With his wife Nicole, he leases the Murchison Oasis Roadhouse and Caravan Park.

Accommodation is in high demand, as are petrol and diesel and the monster burgers they serve at the roadhouse. Peter, who sports an impressive ZZ Top-style beard, grew up on stations in the district and, after a stint in the mines, came back.

“I didn’t know how much I missed it until I returned,” he says. He loves the bush, the peace and the freedom. “We just go and find a nice spot to camp,” he says of the trips the couple makes to search for interesting geological specimens. The rock of the Murchison and Gascoyne region is among the oldest in the world.

The Pindar two-story hotel, once a busy pub and now in private hands.

One majestic and magnificent example is just 15 kilometres west of the town. Errabiddy Bluff rises from the red dirt to glow golden and eerie on the otherwise flat skyline. Peter and Nicole plan to offer geo-tours soon.

The sheer scale of the landscape between Murchison and Gascoyne Junction can be intimidating — as is the thought the nearest services are 300 kilometres of red dirt track in the distance. These two shires, Murchison and Upper Gascoyne combined, take up more than 107.500 square kilometres, an area almost as large as the North Island.

Little wonder, then, that the premier attractions on this segment of the track involve water — a precious commodity in the semi-arid landscape. Well Number 9, dug to a depth of 10 metres in 1896 by Charles Mitchinson Straker for 90 pounds, is today a well-restored heritage site.

Tranquil Bilung Pool, roughly halfway between Murchison and Gascoyne Junction, is one of the very few year-round natural water holes along the WWP. Its dark waters are framed by vertical cliffs on one side and enclosed by ancient gums on the other.

An old shed on their property is a little museum with memorabilia from a very different time.

Gascoyne Junction, 150 kilometres from Bilung Pool, is another small outpost, with about 25 permanent residents, a shire office, a small museum, a caravan park, a petrol station and a pub that serves meals. Just outside town, a one-lane concrete bridge spans the often-dry Gascoyne River, the longest in West Australia.

When it rains, the Gascoyne flows to the sea at Carnavon, carrying red dirt in striking plumes that stretch kilometres out into the Indian Ocean.

On the remotest stretch of the pathway, the sandstone battlements of the Kennedy Range National Park are a hazy and distant apparition and deserve the out-and-return detour of 26 kilometres for the walks into the hidden world of spectacular canyons such as the Temple, Honeycomb or Drapers Gorges.

Back on the road again, and the scenery is epic with an occasional interruption by granite outcrops and eroded hills before the land takes on a different appearance. Red sand, yellow flowering bull hakea and large areas of spinifex mark the southernmost extremity of the iron-rich Pilbara region.

The historic 12-stand woolshed on Nyang Station, where 20,000 sheep were once shorn annually, warrants a stop before the bitumen of the North West Coastal Highway means the end of unsealed roads.

The historic Nyang wool shed at Emu Creek Station, built in 1912.

Bullara Station, 90 kilometres from Exmouth near the junction of Burkett Road and Minilya Exmouth Road, repeats the story of decline, flexibility and survival.

“We made the move out of sheep due to market volatility, live export pressures and the increasing presence of wild-dog activity,” says station owner Edwina Shallcross. Edwina and her husband Tim are working to secure a future for Bullara Station.

“Because of our prime location near Ningaloo Reef, it is viable that we embrace tourism.” Bullara’s tourism business has been steadily growing since 2010. However, there’s also an agricultural side to the business that happily coexists with tourism.

“We are breeding droughtmaster cattle and hope to continue to grow our agri-tourism for years to come,” she says. Sheep, however, won’t feature in Bullara’s future.

The end of the WWP is now close, and it is on this last leg that there is a one-and-only roadside encounter with sheep. A flock of dorsets grazes peacefully in the almost treeless expanse beneath a pale sky, wintry with distant clouds.

And to think these lands were once Australia’s most productive sheep and wool country.

THE WOOL WAGON PATHWAY ITINERARY

The WWP starts modestly in the tiny ghost town of Pindar and ends with a scenic bang in Exmouth, the gateway to the region’s major attractions, Cape Range National Park and the Ningaloo Reef. They are a fitting reward for all those who tackle the WWP in its entirety.

Day 1: Geraldton to Pindar and onto Wooleen Station (321km), o/n Wooleen Station

Day 2: Wooleen Station to Gascoyne Junction (332km), o/n Junction Tourist Park (cabins)

Day 3: Gascoyne Junction to Bullara Station (412km), o/n Bullara Station

Day 4: Bullarra Station to Exmouth (90km)

Yardie Creek Gorge in the Cape Range National Park near Exmouth is one of the park’s biggest attractions.

The WWP is a one-way trip. Return to Perth via the sealed North West Coastal Highway and the Brand Highway.

NOTEBOOK

Getting around: A 4X4 vehicle is essential. All major car rental companies have a presence at Perth Airport. Although no actual four-wheel driving is involved, drivers must adjust to changeable conditions. Four-wheel driving experience is not needed, just common sense. Stock up on water.

Road conditions: Roads are unsealed but mostly well looked after. The access road to Kennedy Range National Park can be a bit rough. After rain, roads can become impassable and closed for days.

Petrol/diesel: Fuel is only available at Murchison Roadhouse and Gascoyne Junction.

Where to stay: Wooleen and Bullara offer station stays, Murchison Roadhouse has motel-style rooms and Gascoyne Junction can accommodate travelers in cabins.

When to go: The cooler months of June to September are ideal.

More information here: outbackpathways.com

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.