Oamaru couple behind Craftwork Belgian ale make wild yeast brews in a low-ceilinged cavern

An Oamaru couple play with wild yeasts to make Belgian-inspired ales that could put hairs on the chest.

Words: Lisa Scott Photos: Guy Frederick

The hops have gone wild this year, creeping over the roof of the barrel room, flowing down the boundary wall: fat, green, bud-shaped flowers turned up to the sun like a twirled moustache.

Not far from ‘moustache central’ itself, Oamaru’s Victorian precinct where penny farthings and penguin-shaped obstacles hamper inebriated perambulation, Craftwork’s Lee-Ann Scotti and Michael O’Brien make strong Belgian beers because, well, that’s what they like to drink.

The beer names are often a play on words – the influence of Michael the bookbinder – and some feature portraits of the duo by local artist Donna Demente. “Mostly we’re here in this little bubble, so when we go to Wellington in our tweed, we stick out.

People recognize us, come up to us, and we realize we have fans, which is kind of freaky,” says Lee-Ann.

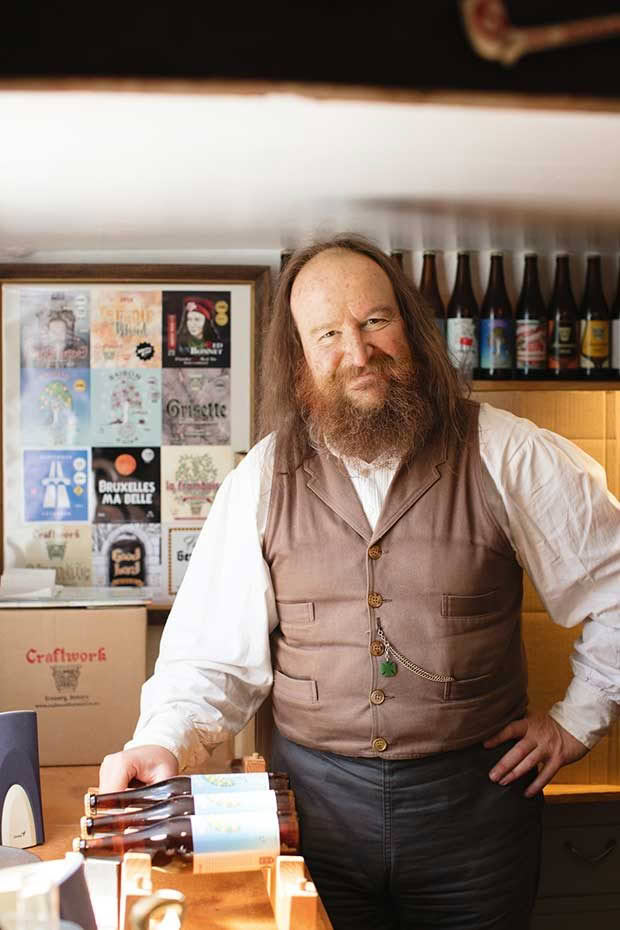

Michael in his waistcoat labeling the Saison Zest and Saison Anise, which are subtly spiced with black pepper and star anise. None of his clothes are props – even so, people have asked to borrow parts of his wardrobe for a movie. “You want to borrow my clothes?” said Michael, his head scraping the ceiling like Hagrid. “I’ll have to go around in my nightshirt.”

In the closeness of a medieval-feeling cellar (‘mind your head’ says the sign and, with the average beer clocking in at seven per cent alcohol, that’s good advice), Craftwork makes beer that wins awards.

Coming away with a gold medal for their Red Bonnet sour cherry beer in the wood-aged category of the Australian International Beer Awards was a real high last year, and showed they’re not afraid to put themselves out there. Pretty ballsy for a brewery that turned four on the Ides of March.

Idiosyncratic and uncompromising, they’re also extremely patient. The process of brewing Belgian-style beer is hellishly slow: one month in fermentation, one in the bottle and 18 months to two years before it’s ready to drink.

This year they’ll also produce gueuze, a variety never made in New Zealand before and the result of a four-year project, blending it this winter to drink over winter next year.

Craftwork glasses are available from the brewery direct and cost $20.

Taking the leap from home-brewing to going commercial didn’t involve much decision-making. It happened organically.

Lee-Ann was teaching reading-recovery classes for six-to-ten-year-olds who thought beer making was hilarious, asking, “Miss Scotti, did you get drunk this weekend?” Michael, meanwhile, was watching his bookbinding business circling the gurgler, and wondering if anyone would pay to restore a 100-year-old bible ever again.

Plus,they needed a dedicated space to brew because it was taking over Lee-Ann’s kitchen.

Mustering the audacity required three factors: bravery, a donation that made it possible to buy a Braumeister (an all-in-one brewing system), and the Riverstone beer dinner which gave them access to brains to pick. Tick tick boom, they were away laughing, although Michael was pessimistic about the council’s compliance requirements.

“I thought it would be nothing but trouble.” Their brew room is tiny and hardly an industrial kitchen. However, “they were really good.”

Hops grow over the back fence; Little River artist Katrina Perano who designed the saison label is descended from a family of whalers and specializes in book plates and tattoo-like artwork full of puns.

The continual struggle and lack of money is taxing – that and worrying about running out of beer. On the plus side, given that Craftwork only produces 100 litres at a time, brewer Lee-Ann can afford to experiment: rebels who break rules and never say sorry.

Their O’ambic (the Oamaru version of Belgian Lambic) is bucketed under a walnut tree in the backyard to get a diverse spread of yeast.

For Lee-Ann the biggest pitfall is ‘idle’ time spent on the computer dealing with suppliers who ask, “Have you been on leave?” Better this part is left to her though. “If some of it brings me close to tears, Michael would be dead.”

Things are now at a tipping point: the dream is to find a 100-barrel storage space. Lee-Ann: “We’ve expanded into Wanaka, and are looking at the Victorian precinct in Oamaru for something with character, a hall perhaps, open once a week for bottle sales.”

Lee-Anne doing the whirlpool, so the particulates fall to the bottom; the oar-like paddle was found in a second-hand shop in Oamaru called Found.

Did they have qualms about being a couple and working together? “No. We’ve been mates since we were teenagers,” explains Lee-Ann. “Actually,” says Michael, “being in a partnership is a massive strength.” They also play nicely with others.

“Because we’re Belgian [brewers], we don’t collaborate, we make connections,” he jokes. Going up to Auckland soon to ‘connect’ with Hallertau, they’ve already co-hopped with Emerson’s, Christchurch’s Punky Brewster and Wilderness, Emporium of Kaikoura, Wellington’s Choice Bros and Wild and Woolly, and Wanaka’s Rhyme and Reason. “While our oeuvre is strong Belgian, we are open to other styles, but it has to mean something.”

A Norwegian alliance produced svak øl (a low-alcohol tipple) while making friends at Pasquale winery resulted in a beer/wine gewurz triple called Faux German and a pinto quadrupel, Dieu Noir, combining the taste of stout and pinot noir (whoever said not to mix the grain with the grape was an idiot, however my handwriting did start to wobble at this point).

Forging connections means, “You can’t be pedantic, judge-y,” although that’s exactly what Lee-Ann soon will be having registered for the US-based Beer Judge Certification Programme being held in New Zealand for the first time this year.

The couple are fans of spontaneous fermentation (“it’s very random”) which could be a metaphor for their fizzing-at-the-bung personalities. They like to take adventures in beer, traveling to Belgium each year, where it’s normal for septuagenarians to be seen at farmers’ markets, trundling a trolley while supping a 10 per cent duvel at 10am.

In September they’ll host a small group tour to West Flanders and Payottenland (see craftworkbrewery.co.nz). They’ll leave Brussels for a tiny village on the border of France, visit Ypres for the last post, and Flanders Fields museum, stopping at hommelhoffs (hop houses) on the way. Visiting World War I sites, a war that shaped the face of North Otago, it’s a way of paying respects too.

Best way to drink Craftwork beer? “Out of our Craftwork glasses, of course,” says Michael. In a meadow while wearing a féileadh-mór (a belted, blanket-like piece of tartan), sipping their Scotch Bonnet. Tricky, but do your best.

WHAT WE’RE DRINKING

Lee-Ann’s favourite tipple is Girardin Black Label, a gueuze also known as ‘Brussels’ champagne’, named after the region in Belgium it hails from. It is made by blending three-year-old, two-year-old and one-year-old lambics spontaneously fermented with wild yeasts then bottled for a second fermentation. Food matches? “Anything, our beer is so good.”

Michael’s not sure if he has a favourite brew, “It depends on the time of day, the food… same with the style.”

People often assume Belgian beer is niche but there’s an enormous variety: trappist, lambics and gueuzes, farmhouse and saisons.

“If I had to pick a desert-island beer for you, it would be an orval,” interjects Lee-Ann. The beer is traditionally made in an abbey on the border of France; with his visitor-from-another-time vibe, as if he’s just come from inking parchment in the scriptorium, it suits Michael to a T.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

MORE STORIES FROM OAMARU

How this small country school is turning a profit from the land

The bookshop at the end of the world: Discover the rare treasures of Adventure Books in Oamaru

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.