What you can tell about your poultry from their feathers

This bird is a ‘frizzle’ where a genetic aberration curls the feathers.

Feathers are a feature of all birds, whether they can fly, swim or just live on the ground, and there’s a lot they can tell us.

Words: Sue Clarke

Feathers are an amazing natural construct. They come in a glittering variety of colours, shapes and sizes, from the magnificent plumes of the ostrich to the iridescent glint on a tiny hummingbird.

Their properties include waterproofing, powerful enough to keep penguins alive and thriving in icy cold Antarctic waters, to the incredible and very large aerodynamic flight feathers of the albatross.

Poultry have quite a wonderful range of feather types, patterns and colours within the various breeds. The Silkie has extreme feathers which look more like fluff or hair. The frizzle has feathers which curl back on themselves all over the body.

The majority of breeds come in a range of colours or with feather patterns including laced (silver laced Wyandotte), pencilled (partridge Wyandotte), barred (Barred Plymouth Rock), ticked (Ancona), or randomly scattered with other colours (speckled Sussex).

Feather colour, pattern and type are inherited. Purebred birds retain their colouring because breeders have carefully selected and perpetuated the genetics to consistently give them the right colour and patterning.

‘Barnyard specials’ can have enormous variation in colour because when you start mixing genes, recessive colours and patterns get the opportunity to burst out.

HOW DOES A FEATHER GROW?

Feathers develop from follicles in the skin, thought to have evolved from the skin of dinosaurs. The earliest feathers are believed to have developed as downy filaments on Theropods, the most famous member of this family being Tyrannosaurus rex, helping to insulate them. Later growth on the upper limbs of bipedal dinosaurs (those able to walk on two legs) assisted in running and flapping which led to flight feathers developing.

The developing feather is supplied with an artery and a vein as it grows, and is surrounded by a waxy sheath. Once the growth is complete, the base of the feather closes off.

This is why you can safely cut the hollow shaft of fully-developed feathers without harming the bird. The waxy covering sheath is preened off by a bird as the feather emerges.

A feather takes three weeks to grow to 75 per cent of its final size, and another three weeks to develop the last 25 per cent.

THE MOULTING PROCESS STARTS ON DAY 1

There are several stages of moulting, starting on the day a chick hatches, to the day the bird is officially ‘mature’ with an adult set of feathers (18-30+ weeks, depending on breed).

Age 0-6 weeks

The first moult finishes when the last of the down is replaced by juvenile feathers.

Age 9-10 weeks

The body feathers are replaced but the tail feathers are not.

Age 12-16 weeks

The wing and tail feathers are replaced.

Once a hen is fully mature and ready to lay, all its pointy-ended juvenile wing feathers will have been replaced by round-ended adult feathers.

Feathers are replaced in a set order and this can help you if you have a bird that is of laying age but not laying. The feathers can tell you what’s going on and why.

The easiest place to check for whether a bird has adult feathers or is still retaining some juvenile feathers is on the wing.

Any remaining feathers which are pointed at the tips indicate that maturity has not yet been achieved due to circumstances affecting the bird and delaying maturity.

Feathers also give you a good indication as to how well a bird has been reared and whether there have been any interruptions, like a change of feed, disease or other stress during the period from 12-18 weeks. A fine line going right across a feather/s (particularly wing or tail feathers) indicates a stress at the time of development and are known as stress bars.

Bent over or ragged tips on the first wing feathers of a chick may indicate stress during hatching, eg the wrong temperature, or a lack of oxygen.

THE FEATHERING PROCESS

A chick at hatching is covered in down. This can be of varying colours according to what the future feathers will be like. Some breeds can be identified by the markings and colours of their down.

The feathers themselves soon grow along a set pattern on the body. The rate of feathering is governed by genes which are also breed specific.

Birds can be either slow feathering or fast feathering. Light breeds like Leghorns tend to be fast feathering, which means the feathers appear within days of hatching.

The wing and tail feathers appear first, and even at hatching the primary wing feathers will have emerged along the wing edges and start to open up like little paint brushes. The body feathers grow next and by weeks 3-4, the chick will be completely feathered.

Heavy breeds like Rhode Island Reds and Orpingtons tend to be slow feathering. At hatching the feathers along the wing edge will be barely noticeable, and the same length as the feathers which emerge from the blade of the wing.

These birds will have only wing feathers and a stumpy tail by weeks 3-4, and may not be fully covered in feathers until they are about six weeks old or older.

This rate of feathering can be very useful. The gene for the rate of feathering is carried on the sex chromosome, so you can accurately sex males and females at hatching if one parent is a slow feathering breed and the other is fast feathering.

In genetics, slow feathering is dominant and fast feathering is recessive. If you take a fast feathering male breed and mate it to a slow feathering female breed then the female offspring will take after the father.

However, this will only be an accurate way of sexing the chicks in the first 24-48 hours after hatching. Once past that point, the feathers will have grown too much and be too similar.

Some heavy breeds which are pure (homozygous) for slow feathering may also be sexed by feather development.Males, carrying two copies of the slow gene (KK), will feather more slowly than females which only have one copy of the slow gene (K-) but it takes some experience to differentiate between the sexes of feathering in chicks which are all slow feathering.

IN FAST FEATHERING

Left: primaries, Right: secondaries

In fast feathering, primaries erupt on the edge of the wing of a chick at hatching.

These are usually at the ‘paintbrush’ stage of opening, and are much longer than the secondaries that erupt further back on the wing.

IN SLOW FEATHERING

Left: primaries, Right: secondaries

In slow feathering, both primaries and secondaries are short, the same length and unopened.

WHERE FEATHERS GROW

Feathers are not randomly scattered all over the body but grow in a recognised pattern in most species of birds across different areas.

If you look at an ‘oven ready’ raw roast chicken, you can easily observe the pimples where the main feathers erupted, and the areas of fine skin that had no feathers.

There are also areas which have no feather growth apart from some downy filoplumes. The most noticeable bare areas are under the wings, down either side of the breast feathers and over the pelvic area either side of the saddle area.

THE ANNUAL MOLT

When a bird moults, it usually follows a set pattern of feather loss. Some birds may drop a whole lot of feathers seemingly overnight and become quite bare apart from a few wing feathers.

‘Pimples’ on a raw roast chicken show you where feathers once were and how the patterns are dense in some places, and sparse in others.

Others may drop feathers from various areas so slowly you may not notice unless you part the feathers to find rows of wax-covered ‘pin’ feathers already poking through under the main body feathers.

Adult poultry tend to first lose feathers in this order:

1. head and neck;

2. saddle, breast and abdomen area;

3. wings;

4. tail.

HOW MOULTING SHOWS YOU THE GOOD AND BAD LAYERS IN YOUR FLOCK

A good laying hen will tend to continue laying while dropping body feathers and not stop until the wing feathers fall out. They may then lose those feathers in dramatic fashion, quite quickly, and suddenly show bare areas over much of their body.

Poor layers stop laying sooner, start losing feathers earlier, take a long time to complete the moult, and may not lay again for 6-7 months. They may also shed only a few feathers at a time, rarely showing bald patches.

ORDER OF MOULTING

When the wing feathers moult, they are lost and replaced in a set order. This can tell you how the moult is progressing because you can work out what stage of loss and replacement the bird has reached.

The primary wing feathers are shed first, starting from the central axial feather and working out to the end.

The secondary wing feathers, the quill feathers closest to the body, are not lost in such a set order as the primaries. The last to go are the axial feather and the one next to it.

On examination, if a bird is found to have fully-developed new primaries before starting to moult her secondary wing feathers, it’s an indication she is a good layer and has laid well into the moult.

Some really good layers, like the commercial hybrids, may not moult their primaries at all for their first laying year and carry them into the second year.

HOW TO CLIP WINGS

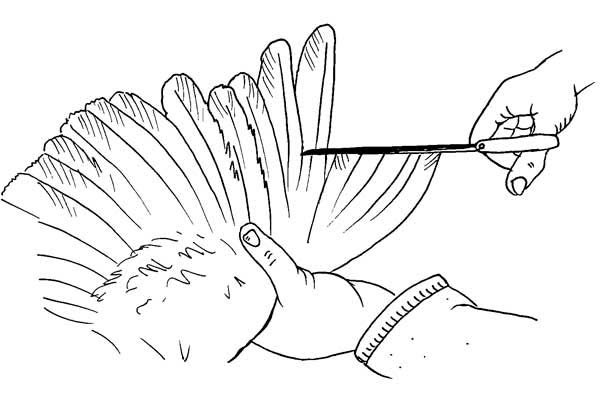

You can cut away the flight feathers on one wing of a bird reducing its ability to fly over high obstacles and fences.

A lot of people think you need to cut off great swathes of feathers but that’s not correct. Use sharp scissors and cut about half of the longest feathers (the primaries) on one wing. If a bird does try to flap, it will tip to one side.

Don’t cut off more than 6cm of the primaries, which are the first set of feathers from the tip. When the wing is folded the cut ends should be invisible, tucked under the secondaries.

The feathers you trim will fall out and replacements will grow the next time your bird moults, so wing clipping needs to be done annually.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.