8 tricks to successful pear growing

The pear season is over and there are always lessons to come out of it.

Words: Jenny Somervell

The last of the pears are picked. The surplus has been stored, packed in preserving jars or given away to friends.

This is the time we reflect on what could be done better for next year’s crop. Each year we learn more and summer 2018 was a challenge.

We live in Oxford, 55km north-west of Christchurch and the continuous, searing, mid-30°C days was a test for our orchard.

Jenny’s garden is small but crammed with bountiful fruiting trees.

The stone fruit succumbed first. High humidity provided the perfect breeding ground for brown rot and most of it never made it to the kitchen. The apples did better.

But the fruit that came out tops was our unassuming and undemanding pear trees. They quietly sized up and ripened, albeit early and rather quickly, but without fuss.

They bore bucket loads of fruit, only mildly blemished. Some were small and could have done with an early summer thinning (next year!).

Even our espalier, only three years in training, managed to produce its first fruit, despite a serious mid-summer haircut. Here’s what we’ve learned about these golden fruit.

PEAR PREFERENCES

There are fewer pear varieties than apple, but they are similar (and a little easier) to grow. They all like a deep, free-draining, slightly acidic soil, will tolerate clay (or temporary wet conditions) better than apples, dislike sandy, alkaline or chalk soil, and will give up completely if there is waterlogging.

THE OLDIES ARE GOODIES

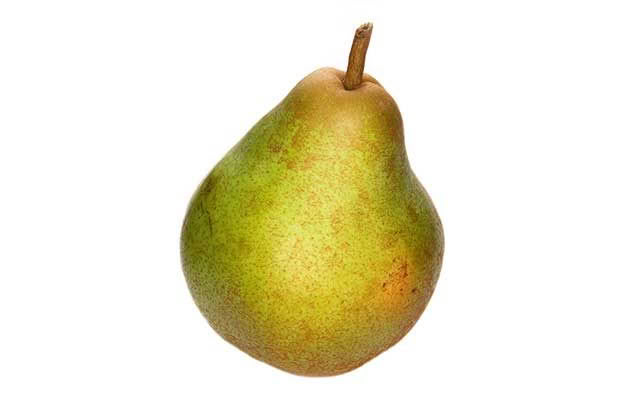

William’s Bon Chrétien.

Many of the best home garden varieties are heritage varieties from the 19th century. After much discussion, we chose six varieties:

• William’s Bon Chrétien, green and red varieties

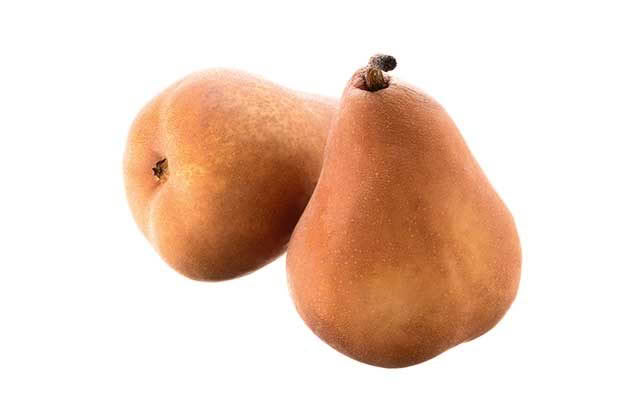

• Beurré Bosc

• Taylor’s Gold

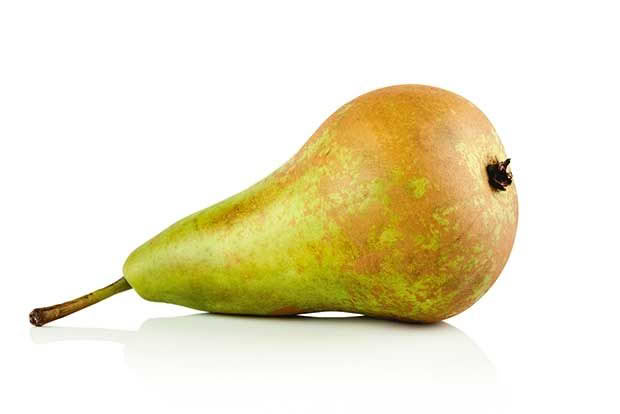

• Doyenné du Comice

• Winter Cole

This gave us some gourmet pears, compatible pollinators, and a range of ripening times and uses.

PAIRING UP YOUR PEARS

All pears should be planted with pollinators, that is other pears which have the same flowering times. Other considerations are spreading harvest time, the intended use of fruit (eg, dessert, preserving) and keeping qualities.

Pears are a good example of when it pays to have a planting plan.

TAMING THE VIGOUR

Pear trees on their own roots produce very vigorous, large trees, slow to crop and prone to disease.

We are fans of dwarf or semi-dwarf trees, the best option for the home garden.

Dwarf trees are pears grafted onto Quince C rootstock. This restricts them to about 2.4-3.5m high and means you can grow more varieties in a small space. Instead of towering over you, you can walk among them picking fruit rather than finding, dragging and climbing a heavy ladder.

They do need strong stakes and a richer, more fertile soil, but they more than make up for it:

• they fruit earlier

• they are very productive for the space they take up

• you can train them as cordons, espaliers or fans, and trees can be bought pre-pruned

• you can buy trees with two grafts giving you two varieties and a built-in pollinator.

Semi-dwarf trees are grafted onto semi-vigorous Quince A rootstock, and produce stronger trees which grow to 3-6m. These are a better choice for poor soils as they are a little less fussy about soil.

BARE ROOT OR CONTAINER?

Pear trees are sold either with bare roots or in containers. Bare root trees tend to have a stronger root system than container-grown ones.

Bare root trees can be bought from specialist nurseries, and you will get a much wider choice of varieties. They are shipped with the rootball wrapped in moist sawdust, are only available in winter and need to be planted in June, July and August.

Container-grown trees can be bought and purchased at any time of year. However, planting in winter is preferred as it allows for better root development before the tree commences active top growth.

Trees can be bought aged one, two or three years old. Older trees will have been pruned to develop shape, which can be an advantage if you are a pruning beginner.

TRAINING

Most pears are pruned and trained with a central main stem or leader as the foundation. Side branches or scaffolds grow off this, forming a conical or pyramid shape. Scaffold branches should be about 30cm apart. This is the simplest method to growing a compact, easily managed tree.

The basic idea of pruning is to develop well-spaced, balanced branches. Take out any that are broken, diseased, dead, or crossing over.

The blossoms grow from spurs. Once pollinated, they become fruit. Too many bunched together and the fruit won’t grow well so thinning is important.

Remove suckers from the base, and any limbs along the trunk that are getting bigger in diameter than the trunk. Cut back vigorous vertical branches.

Like apples, pears fruit on wood that is two years or older on short, stubby spurs. Spurs are formed by cutting back laterals to form short side shoots. Pears form spurs readily and quickly become overcrowded and unproductive. Old spurs should be thinned.

GO VERTICAL

Cordons, espaliers and fans are a great way to use vertical, north-facing space, and are convenient for picking, pruning and spraying. For the first few years you need commitment to consistent pruning in summer and winter to establish the structural branches.

It is important to start with a maiden ‘whip’. This is a 1.4-1.6m single-stemmed, unbranched tree or – preferably – a ‘feathered’ maiden (one which already has side branches).

Choose a north-facing site that is sunny and sheltered. Work well-rotted manure and all-purpose fertiliser in the soil as you plant the tree.

Attach strong horizontal wires at 30-45cm intervals to a wall, or to secure posts with strainers so they can be tightened.

Espalier

This is a strong, dramatic form and can be used effectively to partition different parts of the flower or vegetable garden. An espalier has a centre leader with horizontal tiers, obtained by removing the head and training the laterals horizontally on a wire frame.

- A young espalier pear tree.

- A pear espalier.

Training takes time. Expect several years of input to get multiple tiers.

Cordon

This is a single-stemmed tree with lateral branches pruned back to short side shoots or spurs on which fruit is born. Cordons

can be upright or oblique (at a diagonal) and trained into double (U-shaped) or multiple forms.

For a single cordon, cut the main trunk back to about 25cm from the ground after planting. Shoots will sprout from the stem. Remove all but one. For a double cordon leave one each side of the stem.

A pear pruned into a fan.

Fans do not have a central leader. Instead, laterals or ribs spread out either side of a short central trunk.

We tried all of the above. We discovered that of all our fruit trees, pears were the most adaptable, making them a good choice if you’re are a beginner to espalier.

7 TIPS FOR PLANTING PEARS

Do a good job and don’t skimp on tree quality or preparation.

• Mix up to one third (but not more) by volume of compost or organic matter into the soil.

• If any roots are encircling the root ball, pull them straight or trim them to the straight point prior to planting.

• Make sure the graft union (the swelling where the cultivar meets the rootstock) is 5-10cm above the soil line to avoid suckering.

• After planting, water thoroughly. Newly-planted trees need watering weekly for the first year to keep soil moist (but not waterlogged).

• Tie the tree to a strong stake to encourage a strong trunk and to stabilise it so roots can establish. Remove after 3 years.

• Pears will grow better if grass is removed around the trunk and organic mulch added.

• Avoid planting in the path of strong prevailing winds or in frost pockets.

VARIETIES

William’s Bon Chrétien (also known as ‘Bartlett’)

This popular, early dessert variety was the pear my mother sought for bottling. Fruit is squat, juicy, with green skin, faintly striped red. It starts to fall off the tree in February (late January for us this season) but is best picked green as it can be hard to judge ripeness. Eating or cooking.

Pollinators: Doyenné du Comice, Beurre Bosc

Beurré Bosc

Classic pear shape with a particularly long, curved neck. Fruit is rough-skinned, russetted and golden brown. Very sweet and flavoursome, juicy, creamy flesh when ripe (gritty when not) and holds together in cooking. Stores reasonably well. Ripens mid-February/March.

Pollinators: William’s Bon Chrétien, Doyenné du Comice, Conference

Doyenné du Comice

Grown well, and picked at the right time, this dessert pear is outstanding, sweet with melt-in-your-mouth juiciness. If not, it can be grainy. Refrigerate before ripening. Fat and squat, yellowish green with a pink blush. A tendency to biennial bearing. Ripens late February-March.

Pollinators: William’s Bon Chrétien, Conference

Seckle (honey pear)

A small, reddish-skinned pear with sweet, juicy, perfumed flesh and exceptional flavour. Ideal for home gardeners. Ripens on the tree in March but doesn’t keep well.

Pollinators: Partially self-fertile.

Conference

Medium large, mid-to-late season dessert pear, with elongated, green russetted fruit and sweet, juicy, melting flesh. Reliable and heavy-cropping for eating or cooking. Ripens March-April.

Pollinators: Partially self-fertile, helped by William’s Bon Chrétien

Taylor’s Gold

This won a place in my garden for its attractive, russetted, browny-gold skin and fruit quality. Said to be a mutation of Doyenné du Comice, with similar size, shape, and sensational flavour. Ripens March.

Pollinators: William’s Bon Chrétien, Beurré Bosc

Winter Cole

Late pear, juicy with rich flavour, stores well or can be preserved or juiced. Tree has a spreading habit.

Pollinators: William’s Bon Chrétien, Beurré Bosc, Doyenné du Comice, Taylor’s Gold, Winter Nelis

Winter Nelis

A late pear which stores well. Firm, fine flesh suits eating or bottling, but can be a bit grainy near the core. Eating or cooking.

Pollinators: William’s Bon Chrétien, Doyenné du Comice

MORE HERE:

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.