Tattoos and eco-printing: Why this Featherston couple built their life around permanent pigments

Mario and Ceara fitted out their studios over the 2020 lockdown, doing nearly all the work themselves. While Ceara was brought up in Henderson, West Auckland, Mario is from Slovakia, where he played guitar in punk bands. Slovakian punk, he says, is different from Western punk. It’s slower, more melodic and very political, especially back in the 1990s when it was all about communism, oppression, and the lack of free speech.

A Featherston couple has set up two studios, separate but connected, on the town’s main street. While one favours neutral hues, the other — hailing from the Eastern Bloc — is drawn to a profusion of pigment.

Words: Lee-Anne Duncan Photos: Esther Bunning

There’s a hum on Featherston’s main street. It’s coming from connecting studios — Perpetua and Konstantin. Ceara Lile sits at her sewing machine behind Perpetua’s open door, the whirring needle carefully appliqueing single block letters onto cushion covers sewn from vintage woollen blankets. Her eco-printed silk garments hang rippling in the light breeze coming from the street.

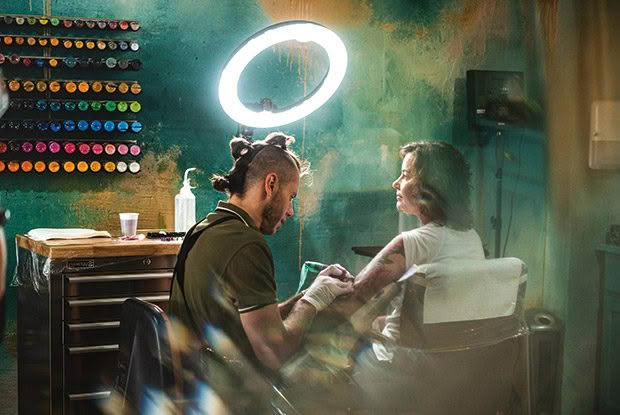

Beyond the closed connecting door, her partner Mario Gregor is also bent over a buzzing machine, his needle pushing ink into a client’s skin in his own studio, Konstantin. The tattoo is a dahlia, vibrant with purples, yellows, and blues — a bright and beautiful piece of permanent art.

Mario Gregor, tattoos a dahlia on Louise Boulton’s arm. It’s Louise’s third visit to Mario, adding to the flowers that now grow down her upper arm.

The names of each of the studios reflect permanence. They’re also the names of Mario’s Slovakian grandparents, as he grew up in a small village in what was called Czechoslovakia until 1993.

Aged eight at the time of the Velvet Revolution in 1989, Mario remembers the country’s excitement at shucking its communist past. “I remember a big parade, with people handing out dove badges because we were all free. It was huge.”

Gradually, Mario’s world began to take on colour. “In communism, everything is grey and beige. Eastern Europeans are quite famous for using bright and strong colours, and I think it’s because creatives coming out of that place have gone, ‘What? There’s colour in the world?’ Boom. And they go crazy. When I started tattooing, I would put the brightest blue against the brightest orange — it hurt your eyes, it was so crazy bright. It’s been a progression to find the subtleties, to mellow it down, and still look amazing.”

- Ceara Lile drafts up a pattern for her next garment.

- Ceara’s love for nature is reflected in her studio, with its wood paneling and the driftwood clothes racks that she and Mario constructed. She decided that eco-printing was where she wanted to focus her creativity when she and Mario were on their BMW R1200GS adventure motorbike.

While Mario rebels against the colour-challenged conformity of his childhood, Ceara’s preference for cool, natural tones is an embrace of her own. Growing up in West Auckland’s Henderson Valley, she spent her early years in the Waitākere Ranges and on nearby beaches — she even worked as a guide, taking tourists on bush and beach walks.

That deep appreciation of nature has led her (via a fashion degree, then graduate diplomas in teaching and psychology, tending a London bar, selling advertising features, and running her and Mario’s previous tattoo gallery) to reignite her creativity by eco-printing fabric.

“I was always doing a little bit of hand-sewing, beadwork or something as a way of keeping sane. I can’t sit still unless I’m doing something useful with my hands. I’ve never had room for a sewing machine, so I had to do things that didn’t take up space.”

- When Ceara was a fashion student, before sustainable fashion was even a thing, she wanted to position herself away from the industry’s wastefulness.

- “I kept coming back to the idea that I’d like an organic, ethical fashion shop, where everything was done as environmentally sustainably as possible. But it was in the late-1990s, and that couldn’t be done easily.”

- Now she can follow her sustainable focus with ease, using plant pigments to eco-print on fabric. “I’m excited about printing with plants from where I live, but I’m really excited at the idea of taking my gear on holiday and playing with different water and leaves while we’re away.”

Now she has space — both at the Featherston home she and Mario share and her studio, where she spreads out fabrics and covers them fresh leaves dipped in a mordant made from rusty water.

The material is then rolled and boiled for the leaves to impart their pigment. Afterwards, she or her machinist sews the printed fabric into scarves, pillowcases and garments.

“I’m big on making as little impact on the environment as possible, and it’s important to me that my clothes are made in the same economy they’re sold. I make clothes that rely on a sense of environment, so the leaves I print with are from around here, usually from my backyard.”

Ceara brews a fine kombucha and Mario a delicious fruity schnapps that also reminds him of home (although the pair drink very little alcohol). They ferment an annual batch of sauerkraut, make Slovakian sausages and the poppyseed cake Mario craves.

Mario is also is onto his second career — his third, counting the fruit picking that brought him to New Zealand. With a master’s in engineering (cooling and heating systems), he was fixing to do his PhD in Canada until he realized it would cost about 250,000 Slovakian crowns (approximately $11,000), an “unimaginable sum”, at a time when the average wage was 9000 crowns a month.

Instead, Mario took a job in a factory in the Czech Republic and began to save after hearing about fruit picking in New Zealand.

“For two months, I spent the minimum and saved enough to buy a flight. Immediately I quit and went back to Slovakia to tell my parents I was going to New Zealand. Under communism, you were assigned a job, and you did that job until you died. Here I was, telling them I was quitting and going to the other side of the world to pick fruit — yes, after all that study. Oh, and can I please borrow some money?”

A keen motorcyclist, Mario is restoring a 1970 Harley Davidson Sportster XLH 900. “I bought it from a Featherston local. The bike owner’s mum was a World War Two Polish refugee who arrived in New Zealand during the 1940s. I guess we shared some Eastern European bond because he had the motorcycle for more than 20 years as a project and wasn’t going to sell it, but that changed once we’d met.”

After five months picking and odd-jobbing in Hawke’s Bay during 2005 and 2006, Mario returned to Slovakia but immediately saved to come back, arriving in Nelson over New Year 2006/07. Hungry and unable to work because of a motorcycle injury, he met Ceara over the free food table at a youth hostel.

“I was walking the Abel Tasman before going to teach in Thailand,” says Ceara. “I’d noticed him before the walk and ran into him again when I came back. We started talking, even though Mario could barely speak English.” “I thought I was fluent, but it was not sufficient,” says Mario.

“I asked Mario to come and get a coffee, and he said sure. But he ditched me because, as I found out later, he couldn’t afford even a coffee. He met me after, and we chatted for hours until I had to get my bus out of Nelson. That was that, but we kept in touch.”

They reconnected in Taupō just before Ceara moved to Thailand, where Mario joined her a few months later. “That’s after spending only five days together. But we’d emailed and messaged so much. We’d told each other everything,” he says. Nine months later, they left Thailand, visited Mario’s parents in Slovakia, then flew back to New Zealand, settling in Nelson.

Something had changed during that time in Thailand. Mario had had his first tattoo — two, actually. “It was much cheaper in Thailand, so I got the Chinese characters for ‘freedom’ on my leg, then went back and got a huge Gregor crest on my back.” And he wanted more.

Because of his DIY bent, or his communist upbringing, which didn’t allow spending on luxuries, Mario decided to tattoo himself. He bought a tattooing machine and set about learning the art.

“Learning was hard because I didn’t have many friends to practise on. I tattooed Ceara, doing the first flower on her arm. I thought it was awesome when I did it, but now I look at it… She was so brave.” Adds Ceara: “That’s love, right there. It’s been reworked a few times since.”

Eventually, he found someone else willing to let a novice get under his skin. “My first tattoo was a little black widow spider on a young fella’s shoulder. It was scary because I would be lying if I said I knew what I was doing,” says Mario.

- While Mario’s mohawk and tats hint at punk, he got them after he left Slovakia, as even a mohawk was too much for those conservative times. “When I went back to Slovakia in 2008 with my mohawk, I couldn’t even get served at the deli. It was like I wasn’t standing there. It is better now, though.”

After moving to Wellington, in between jobs installing heating transfer ducting, Mario built up an artistic portfolio. “Every lunch break, every smoko, I had a pencil in my hand and was drawing and drawing.” After work, he’d tattoo anyone who would let him. Eventually, he heard about a job in a tattoo studio. “It was tough because I only got paid when I tattooed, and it took time to build a client base.”

Mario developed what he calls a “watercolour style”, where his tattoos fade into the skin. Soon he found himself booked up weeks, then months, in advance. Wanting to work together, Mario and Ceara set up their own shop in Wellington in 2015, eventually having six tattoo artists on staff.

Ceara and Mario on their BMW R1200GS adventure motorbike. “At the time, we were commuting into Wellington to run our tattoo gallery there, but I was unsettled. I couldn’t even really think about what I wanted. But on the motorbike, we can talk through our intercoms, and I felt able to say, ‘I want to start making things again.’”

With that came more admin and management, especially for Ceara, who ran the business. Both were feeling unfulfilled and exhausted from commuting between work in Wellington and Featherston, where they had moved.

The solution was a space on Featherston’s main street, which became available in early 2020. Lockdown provided the opportunity for the pair to strip back and fit out the shop to suit themselves — bright colours on Mario’s side, cool tones and wood on Ceara’s.

The new studios have brought many benefits. “It’s incredible how many other artists we have met since opening,” says Ceara. “Sometimes we look at each other and say, ‘Aren’t we quite the arty-farty couple?’”

MARIO’S “WATERCOLOUR” TATTOOS

Mario Gregor’s tattoos are so life-like it seems possible to stroke the tūī’s shining feathers, wipe the dew from a crimson capsicum, or smell a rose’s aroma. His style is painterly, romantic — not what first comes to mind when thinking about tattoos.

“I will do a skull if someone wants, but it would probably have a flower in it. I primarily do realistic work but make it look like it’s a watercolour or painting. I usually add a background, so it looks like it’s flowing off the skin. I want the tattoo to look like it has always been there.”

Mario’s speciality is New Zealand flora and fauna and landscapes. Clients first come for a consultation, telling Mario what they’d like. He then creates a detailed design, adding his twist. “When you enter ink into somebody’s skin, you are changing their lives. It is quite exhilarating. I had a school friend who was very anxious, but after his first tattoo, he now feels so much better. I can affect people’s minds in a positive way.”

It’s rare to find someone with just a single tattoo, as one tattoo seems to beget another. Mario believes it’s because that first ink breaks a mental block about tattoos.

“It’s opening the door to uncharted territory when you step into a tattoo shop. You get one, and you discover that it doesn’t hurt as much as everyone told you, that your life doesn’t fall apart because you have a tattoo, and you don’t regret it. Your perspective changes — then you get another.”

As for how painful tattoos can be, Mario says it depends on the person and their state of mind rather than the body part. “The sorest tend to be the elbow and the shoulder as there are many nerves there; behind the knee is painful for some, but not for me. If you’re stressed or tired, it’s more painful.” inkedbymario.com

CEARA’S ECO-PRINTING PROCESS

A green leaf imparts a green imprint, right? Not always. “Actually, silver dollar gum leaves at a certain time of year can give a lovely bright orange,” says Ceara Lile.

Ceara became interested in eco-printing — using only natural processes and materials to print — a couple of years ago, then did an eco-printing workshop. “I thought, ‘This is freaking amazing.’ Eco-printing brings together everything I love — being connected to nature, as well as sewing and textiles.”

Eco-printing involves many chemical reactions. Ceara first collects leaves she knows — or hopes — will create a nice colour and shape on the fabric.

She then mixes up a “rust” water made from discarded rusty-metal “bits and bobs”, usually iron, to act as a mordant to help fix the colour to the fabric. Next the selected leaves are dipped in the rusty water and arranged on the fabric.

With the leaves in place, Ceara rolls up the fabric and boils it for about 90 minutes. Then she unrolls it, collects the leaves for the compost, and dries the fabric. “Eco-printing doesn’t just produce a beautiful product; it’s using a natural resource in a less impactful way.”

Ceara usually prints on silk — sourced from Australia — but also wool or recycled bedsheets. But printing on cotton is tricky because of its chemical composition.

“Silk and wool are protein fibres, and leaves are made from cellulose or plant fibres. Cellulose and protein glue together well, attracting like the opposite ends of a magnet, so silk and wool print quite easily.

“However, cotton is also a plant fibre, so it repels the leaves’ plant pigments. For cotton to be printable, I must first put it through a pre-mordanting process.

I put it in a tannin bath, then a protein bath — usually milk or soy — or an alum acetate bath, rinsing and drying between each, before I can print on it. It’s much easier to print on silk, which needs none of this.

“You never know for sure how something is going to turn out, as so much depends on the leaves, the time of year and the mordant used. There are endless possibilities, and every piece of fabric is a surprise.” To learn more about eco-printing, Ceara recommends the book Eco Colour by India Flint or, even better, attending a workshop. perpetuastudionz.com

MORE HERE

The couple behind Hastings Distillers were led by their noses to create artisan spirits and liqueurs

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.