Why Auckland artist Evan Woodruffe (literally) paints the shirt off his back with colour, texture and whimsy

Evan Woodruffe and Jeanne Clayton’s Kingsland home is draped in silk velvet digitally printed with Evan’s art.

This Auckland artist’s joyous art is an antidote to melancholy. It’s a prescription he’s taking to the world.

Words: Nicola Martin Photos: Tessa Chrisp

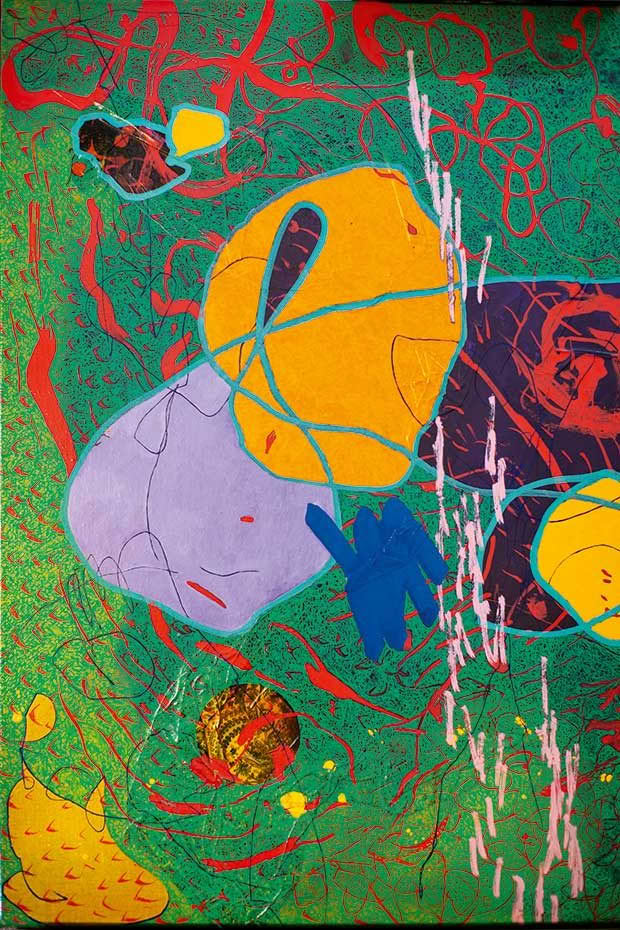

Evan Woodruffe says he has an existential compulsion to create art. The Auckland painter’s giant works are an extension of himself. He uses colour, lines, form and even the shirt off his back to inspire joy and a sense of childlike wonderment.

“In dark times, we need artists to shine a light and remind us of the good qualities of humanity. They lighten our spirit so we can cope with the crises of the world,” he says.

It was that joyous quality that last year caught the eye of Joshua Zong. The director of Auckland’s Ai Gallery asked Evan to travel to Beijing in August to lead a special exhibition called A Colourful World and a Shared Future. The show, at the 8th Beijing International Art Biennale, featured 21 New Zealand artists. Aotearoa was among 100 countries represented but was just one of six awarded a special exhibition.

Jeanne says they do “little things each day” to cope with stress. Jeanne swims at the Pullman Hotel every morning and Evan loves music. Find his playlist on Spotify under “Evan Woodruffe, DJ Phatmouth”, a name his sister Kate helped coin.

The accolade wasn’t a bad result, says Evan, an understated comment from someone whose work is so bold. Evan, one of six siblings, was born in 1965 in Auckland’s then-bohemian East Coast Bays. His mother Vivienne and father John, both artists, had escaped the “British class system” a year earlier.

“It was the 60s, the time of the six o’clock swill and bans on shopping at the weekends. I think they’d wondered where they had landed.”

All of Evan’s siblings have pursued artistic careers of different sorts. Evan’s first art was indie dance music. He sang and played guitar in a band called Melon Twister alongside three of his brothers, Lars, Emil, Garnham and drummer Gary Covich.

At 18, he enrolled in a bachelor of arts at Auckland University of Technology and soon dropped out — he was having too much fun living and making music. But by the time he was 30, he realized he probably wasn’t going to be a rock star.

“I had exhausted the potential of trying an unstructured approach to learning life’s lessons. So I started painting furiously.”

Jeanne won Something Else by Britain-born conceptual artist James R Ford in a raffle. Evan says that until the couple moved into their Kingsland apartment, there was nowhere to hang it.

He spent the next 13 years teaching himself to be an artist, first from a studio on Great North Road in Grey Lynn and today from one he shares with 12 others in Kingsland. To support himself, he worked as a demonstrator for art supplier Gordon Harris.

When people understand the hours and cost (financially and emotionally) that go into making art, not many choose it as a career, he says.

“Who the hell would want to do it? It’s seven days a week, and it often costs at least as much — if not more — in the making.”

A large Imogen Taylor work dominates the dining area. The Frances Hodgkins fellow refers to her art as a “pretty/ugly” mix of Cubism and Regionalism.

But it’s how he feels authentic. “It’s an existential compulsion. We want to make marks on time. But it’s not about grandstanding or saying ‘look at me’. It’s something I can validly give to the world.”

His early work was dark and moody, influenced by the human form. But, even self-taught, it was awarding-winning. In 2003, he won the Becroft Premier Award, in 2011 the Molly Morpeth Canaday Award.

“Painting a person is something we relate to. I was painting myself. There was a lot of confusion and reactions in my work at that time.”

He was working through a lot, he says. Twice divorced at 30, Evan knows the toll the life of an artist takes on relationships. He has been with his now-partner Jeanne Clayton for 12 years, after they met through his sister Kate. Both women had been living in Sendai, Japan, with their husbands; each eventually returned to New Zealand alone.

Evan and Jeanne got together at Kate’s 40th. Jeanne has two daughters — Sacchi and Seira — from her previous marriage and Evan has one daughter, Zinnia.

A cast bronze wētā by Jonathan Campbell.

In Jeanne, he has finally found his match, he says. Their union saw his work start to change, and he began thinking more about progressing it. “I’m still painting myself now, but perhaps it’s much more real.”

The couple purchased their one-bedroom Kingsland apartment in 2017. Jeanne, who works as a real estate agent for Ray White, specializing in apartments, says she found it after looking for the “needle in a haystack” the couple could afford. It’s become a refuge and a home for their art.

She recently launched Something Else Art Soirée, a home-based art-party-hosting business designed to share the couple’s growing collection. It also allows her to match selected artworks with potential buyers.

“I’m quite a good art widow. I think that’s because I have my things happening as well. I’m not sitting at home waiting for Evan to return from the studio.”

In Evan’s top drawer is a collection of wildly coloured ties, a bowl of tie pins ready to fasten them in place. Among the pin collection is one Evan fashioned from a plastic KFC spoon and the tab of a Coke can. He wore it to a society wedding. “You’ll have plenty of time to be casual when you’re dead,” Jeanne says. “Men in New Zealand need to enjoy dressing up more.”

She is the first to encourage him into his studio, to tell him when he’s burning out, and it was she who nudged him, at 48, back to art school. He returned to the Auckland University of Technology and then onto Elam Art School, where he completed a masters in fine arts with first-class honours.

In a self-assessment at Elam, Evan deemed himself “better than average”, his tutor Alan Smith marked him, “adequate, barely so”.

“You were furious at first,” says Jeanne.

The feedback conflicted with his ego, but it also helped him to learn to manage it. It taught him there is always room for improvement.

“You need a certain amount of ego to be able to stand in front of people, to put your art on the wall and let people make judgments on it. But there’s a point where continually telling yourself you’re good enough to do that gets a bit old.”

The provocative painting by New Zealand artist Rohan Wealleans directly above the couple’s bed is part of what they call their “boudoir” collection. “People find the piece confronting, but it’s about power,” says Jeanne, who is a huge fan of shunga, Japanese erotic art. “Life, pleasure, power — everything flows from there.” Another boudoir painting is an Andrew Barber diptych. The piece, called Dick Tip, is a self-portrait of sorts gifted to Evan, who in return created Barber a work dubbed Two-Minute Window.

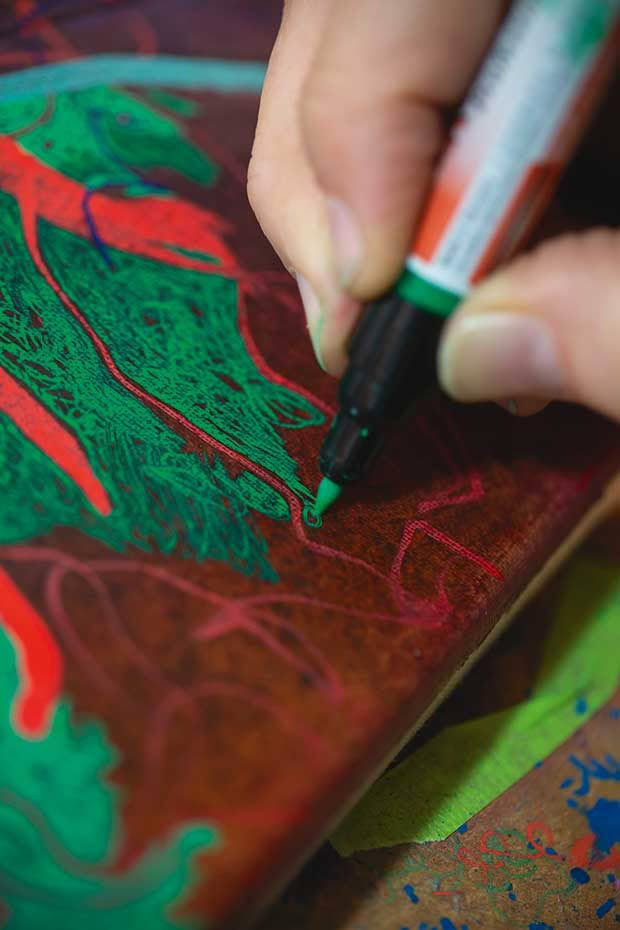

There was an old shirt in his studio and — as frustrated as he was with his work — he threw it on the canvas. “I thought, ‘this will mess it up.’ In hindsight, it made perfect sense. I had always been interested in fabric.”

His clashing shirts and ties are part of who he is, and now they are part of his work. As he layered colour and detail over that shirt, he got lost in the landscape and had to “try and find his way out. I use colour and lines and form to try and create a sense of a place — something that inspires us to feel joy, that sense of childlike wonderment. We don’t get many places like that today.”

That’s why his work has no real focal point, he says. People can look into it and drift around, being drawn into different details. He calls it a “place of dynamic contemplation”.

The couple’s growing art collection includes these Jim Cooper ceramics, which are in the courtyard outside their bedroom. Jeanne says they generally agree on the pieces they buy.

Evan is now on a mission to make art more accessible, adding that the visual arts in New Zealand need more investment. “The government currently gives Hollywood huge breaks to come to New Zealand. Weta Workshop gets subsidized with tax breaks worth more than Creative New Zealand gets in its budget every year. It’s something we need to look at.”

And as New Zealand starts to measure wellbeing, Jeanne says art has a distinct ability to create joy in communities.

Evan regards work as meditation. The peace and quiet of his studio contrasts with the couple’s busy social life and the pressures of exhibiting.

“Wellbeing isn’t just about yoga. People want to see sculpture, art, architecture. They want to go to concerts and the ballet, and they will visit art galleries. They will travel to New Zealand for these things. We aren’t just mountains and bungee jumping.”

Evan is now represented by the Paul Nache Gallery in Gisborne, which has sold his work as far afield as Moscow. And he has continued to evolve.

He has explored the arbitrary nature of lines, chasing live ants across his canvas. He has incorporated soil into his work and has even used one of Jeanne’s silk dresses. Her broken earring made it into part of two large multi-panelled paintings for Beijing.

“They’re things from home, pieces of conversations from friends. It’s quite personal, but maybe people can feel it in there. It’s life.”

EVAN ON COLOUR

“We’re in the Pacific. We have lavalavas, leis and pōhutukawas. But we still hold tight to the monochromatic, melancholic tones of Colin McCahon. I think it’s hilarious.”

Evan with Dowse Art Museum director Karl Chitham. Both men are wearing jackets made by Strangely Normal in Evan’s fabric.

He believes colour is emotion.

For example, his paintings for the Beijing International Art Biennale started out blue. “It was a stressful time for us and they were very blue and dreamy. They weren’t upbeat. I thought, ‘I want to feel better than that, I want to feel sunshine.’”

Evan’s work has also been printed onto silk velvet and made into clothing by Auckland design duo Strangely Normal. And they’ve been digitally wrapped around a Jaguar E-Pace (above), BMWs and Scapegrace gin bottles. He says he looks forward to the collaborative opportunities that showing in Beijing may offer.

“I’ve had people tell me I’ve sold out [because of the commercial partnerships]. I don’t understand that. Am I supposed to have Marxist principles? This is a business. People seem to think if you’re not a suffering artist, you’re not a real artist.”

He says he gets paid for his commercial projects, but the fee is small in comparison to what he would earn from a painting.

“There is this idea that you shouldn’t be making money. But I still have a mortgage to pay.” evanwoodruffe.com

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.