Wellington pop-surrealist artist Rieko Woodford-Robinson paints portraits of native birds in the style of Goldie and Lindauer

A Wellington-based painter’s pop-surrealist works are finding favour among art buyers captivated by the subversive cuteness of her creatures.

Words: Lee-Anne Duncan Photos: Tessa Chrisp

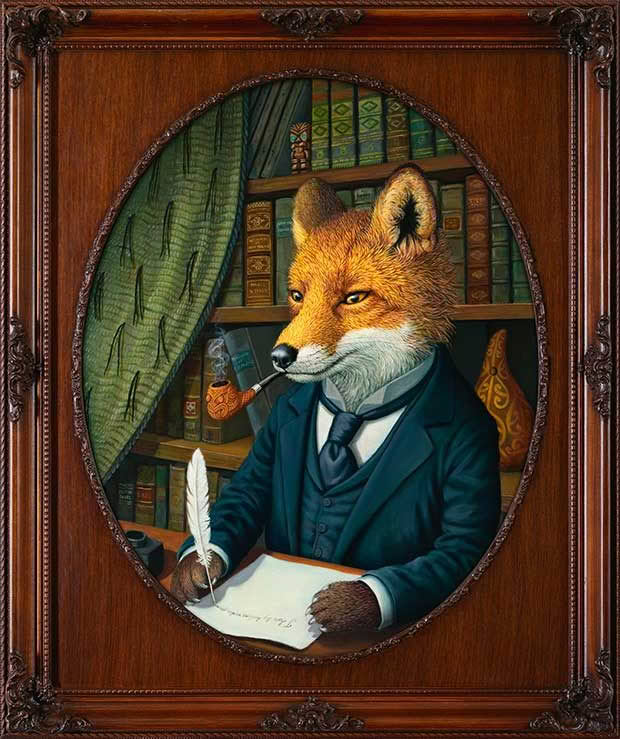

Surrounded by her inspiration, Rieko Woodford-Robinson quietly paints. In delicate strokes, she layers her images in base colours then brushes in detail — feathers, flowers, hair, clothing, background — adding cultural motifs and touches of whimsy. Her paintings could hang on the walls of a Victorian villa. But look again. That’s not a patrician grandpapa, it’s a deer in a top hat; it’s not a kuia in a korowai, it’s a kiwi. The imagery and iconography are familiar and deliberate, but the faces are confounding.

Rieko loves stuffed animals and other toys. Lined up above her easel are antique toys of all types — including an ancient and well-loved dog once owned by her husband’s father, David Woodford-Robinson. It’s neither pottery nor porcelain she seeks in antique shop searches: “I always go straight for the old toys,” she says. Sure, the animals are cute, but Rieko’s anthropomorphism is strategic; she can say more using animals.

“What face would I paint? Someone with a European face? An Asian person’s face? An African person’s face? And animals appear androgynous. It helps people see themselves in a painting if the animal is dressed as a boy but they are a girl. It’s amazing how much easier people relate to animals. And you can see so much emotion through the fur.”

Rieko’s style is pop-surrealism, and extremely popular. Her last exhibition, Aotearoa, at Auckland’s Warwick Henderson Gallery, was red-stickered within days. For the show she painted animals — some native, such as kiwi, huia, kererū, others not — in traditional Māori or colonial clothing, posed as they might have for Goldie, Lindauer or another Victorian portrait artist. Each painting had an antique frame from her collection — Rieko owns about 80, with some up to a century old — adding another layer of history to her work.

It’s a style Rieko has made her own over nearly a decade or so of painting, but its origins can be found in the bush-clad, bird-friendly Brooklyn home she shares with husband Jonno. Above the piano in the couple’s lounge is a portrait of Jonno’s ancestor who visited Gisborne in the late 19th century. It’s unfinished — no one’s exactly sure why — but the painting style, pose, expression, the ornate frame and the connection to the past was an inspiration to Rieko. “I like history, what’s gone before. It makes me want to learn more about New Zealand history and culture,” she says.

Seeing the painting and absorbing its history sparked an artistic adventure Rieko had always longed for but never had the opportunity to pursue. She was born in the small city of Kakogawa, west of Osaka, Japan. At nine years old, she remembers writing a poem with “some kind of drawing” at the bottom.

“That was my first thought that I like creating things. Since then I wanted to create children’s books,” she says. “Not that I was particularly good at writing or painting or drawing, so my parents were like, ‘What are you talking about?’ I was born in the countryside and didn’t know anyone artistic at all. I didn’t have the confidence to tell my parents that drawing was my passion. At that stage, law school was the best option for me as you need to be able to write and show some creative thinking, which I could do.”

Rieko graduated and started working as a law clerk. “I enjoyed helping people. I met many different people from many different backgrounds. But I realized it wasn’t my thing.”She quit her job and planned to move to Tokyo to study children’s books, at the same time applying for a one-year New Zealand working-holiday visa. The visa came through first and in 1999 Rieko landed in Aotearoa. As luck would have it, before leaving home she had met a former flatmate of Jonno’s who recommended she look Jonno up in Wellington. She did.

Many of Rieko’s original paintings are sold with antique frames, which she collects herself. She estimates she has about 80. The painting Kiwi Mother and Child was part of the Aotearoa exhibition held at Auckland’s Warwick Henderson Gallery in October 2018.

Says Jonno: “It was over the Easter holidays and I was working — as freelance film editors always have to work when required — so I only had time to meet her if she came to where I worked. I showed her around the studio, which she enjoyed but found unusual because she hadn’t been invited to anyone’s workplace before.” They married as the new millennium took its first breaths. “It’s easy to remember our anniversary,” says Jonno.

Meeting Jonno was just the boost Rieko needed. His father was an artist (he sculpted Gore’s romney sheep statue). And through his work as a film editor (Mortal Engines, What We Do in the Shadows, Mahana, Pork Pie), Jonno could name many of New Zealand’s foremost filmmakers as friends. “I was surrounded by people who were always thinking about stories and visuals,” says Rieko. “So I was lucky enough to learn how to think and create through them. I didn’t go to art school — although I learned some techniques at a community art class — but I had Jonno’s friends. I’d ask questions, and they’d give me some suggestions.”

Back at the start, in the early 2000s, Jonno put Rieko to work painting backgrounds for the films and documentaries on which he was working. Meanwhile, Rieko worked at a Japanese restaurant and at the Japanese Embassy, then applied to university. “But Jonno reminded me, ‘Why did you come to New Zealand?’ And I thought, ‘Ah. Yes.’ Society was telling me that studying is great, but it’s not the right path for me. So I started making personalized birthday cards, and I made children’s books for friends’ kids for their birthdays. That gave me a portfolio of drawings and writing. And I was using Photoshop and Illustrator to help Jonno, so I was good at digital drawing.”

Rieko began digitally illustrating for Gilt-Edge Publishing, which produces oversized books used in primary schools, and was soon approached by other publishing companies. “Then I realized I needed to work on something with a deeper meaning. I wanted to focus on a single painting, rather than the 24 drawings I must do for a book. I found digital so detached so I changed to painting with a brush, to paint from my body. I believe that’s how you get soul into painting.” And she does — it’s astounding how much expression Rieko paints into the furry faces, how much emotion shines in their button eyes.

Rieko’s painting style was inspired by this unfinished oil portrait of one of her husband’s Jonno’s ancestors. “I love the sense of history old paintings have. I always think about what was happening to those people and what it was like for them back in those times,” she says.

Rieko began copying artists she admired for practise, such as German artist Michael Sowa. “I like his paintings. They have a melancholy, and you feel exactly what the people or animals are thinking. And even though you’d never really see what’s in his paintings — a rabbit in a suit, or a girl walking with a bear, for example — it feels like it’s the right thing to see.” For her first personal painting, Rieko drew on experience. “I’d met two friendly donkeys on Dunedin’s Kamau Taurua [Quarantine Island], then later I heard one had died. So I painted me with the one donkey, both of us together. It’s called Looking for Rosie, and I wanted to get across that she might just be lost, so the remaining donkey still has hope.

The couple live in a 1900s cottage. They renovated in 2006, creating an open-plan kitchen, dining and lounge area. They love how sunny the room is and that it gives them easy access to a patio where birds wait to be fed. “We often feed them raisins,” says Jonno. “They know the difference between organic and normal — they don’t like the normal ones. Makes you wonder.”

“I always have so many little cute things running around in my head. I would like people to have access to my art and hope it brings them joy and curiosity.” To extend that access, Rieko’s images — originally painted in oil — are available as archival prints at Eyeball Kicks Gallery in Wellington, including those from her latest exhibition.She also uses her talents to help others. Rieko could not have children of her own but focuses on encouraging the young, organizing an annual children’s art exhibition and holding workshops for kids. And she and Jonno support the Karunai Illam children’s home in India, founded by another Wellingtonian, Jean Watson. (Jean, who died in 2014, was the subject of the 2014 documentary, Aunty and the Star People.)

The blind in the lounge is made from linen designed by British artist Melissa White based on late 17th-century painted cloth. The rug is a handmade Khal Mohammadi Afghan Turkoman carpet.

“I have been to India to see the work they do and make that direct connection. Back in 1997, I also went to meet orphans, street children who go to school in a park. I did drawings for them and helped them with school work. I am interested in helping children to express their feelings through art.” As for Rieko’s family back in Japan, she says they now appreciate her artistic drive. “It’s taken about 15 years to turn their thinking around but they understand what I’m doing with my life. For me, art is not just about painting and selling the artwork; it’s about bringing culture and history to the people, and it’s about giving minority people — of which I’m one — a voice.

“With every show, I have thoughts I want to share. With Aotearoa, it was 125 years since women’s suffrage, so I was thinking about New Zealand history and all the things that were happening back then. I wanted people to look at my paintings and also think about that. But the show was also about hope for the future because many of those issues — such as immigration and inequality — we also face today.

“But I’m not preaching. If someone feels something about my painting, I’m happy. If they think, ‘it’s cute, it’s a pussycat’, I don’t mind that either.”

SIROCCO AND MANU WHENUA

Rieko had been painting native birds in traditional Māori clothing long before her Aotearoa exhibition. One of her most striking works is titled Manu Whenua, which features a kākāpō. But it’s is not just any kākāpō: it’s the famous Sirocco, the bird that got up close and friendly with actor Stephen Fry.

“Jonno and I love Zealandia in Wellington, and I met Sirocco there,” says Rieko. “I was so impressed by him — he looked so much like a chief,” she says, imitating his ponderous, dignified walk.

“It was like he was welcoming us, rather than us being there to watch him. So I painted Manu Whenua and asked my friend Sam Palmer to carve a frame for it. He also carved a frame for He Rangatira, which features a tūī.”

Rieko wanted to associate Manu Whenua with the kākāpō recovery programme, so wrote to both the programme and its iwi partner, Kaitiaki Roopu, for permission. She then donated the full price of the painting’s sale to the programme. “I felt like I couldn’t have painted this if I were living in Japan or anywhere else. I was living here, learning the culture, meeting these beautiful birds and people. All of that had come into my body, and I was expressing it back through this painting. I wanted people to understand and think about how important it is to protect our native species, such as the kākāpō.” riekowoodfordrobinson.com

RIEKO’S FUTURE PROJECTS

Having created picture books for others, Rieko is keen to develop her own. “I want to make a beautiful picture book about ethnic diversity. It’s so important that minority people have a voice. When I was working in the law in Japan, or with kids in India, my ability to really help people was limited. But I hope my art can tell stories that connect the past with today and make people think about difference and diversity.”

She’s also planning two new exhibitions. One is to be titled Hero and the other New Zealand Toys. “I want to find out about the first toy made in New Zealand and paint about that and other early toys. Also, I want to paint real animal heroes, but not just war heroes — they could from be famous stories or personal experiences, it doesn’t matter. Some animals go well beyond what we believe they are capable of concerning their skills and emotions to help others. So I need to find out more about New Zealand animal heroes.”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.