Walking Wellington: Take in the sights and senses of the nation’s capital, feet-first

The Katherine Mansfield sculpture by Virginia King is best seen illuminated at night. Located at one end of Lambton Quay, the work captures the essence of Katherine Mansfield, who wanted to be known first as a writer then a woman.

A writer/photographer takes a walking tour of the country’s capital, stopping for swirling sculptures, naked models and extremely good cake.

Words & photos: Chris van Ryn

I walk Wellington. The city centre has come into my life at walking pace. I walk without a destination just for the sake of walking. A kind of aimless wandering. Aimless, but a portal, too. To something else; something yet unknown.

I walk to Pravda for a straight-from-the-kitchen cheese scone. And The Lab, for a long black with hot milk, which arrives in a small glass chemistry beaker. I walk to the Higher Taste for a vegetarian meal or La Cloche for an indulgence of the palate. Or hot yoga, to stretch for the next day’s walk.

I live smack bang in the city centre. Around me is a ribbon of reclaimed land that tracks the waterfront. Pancake flat. Behind this 1840 reclamation, the landscape tilts upward. A stroll along Lambton Quay alters abruptly, up alleys, up steps to The Terrace, from where I wend my way further up through the city cemetery, rudely bisected by the motorway, assaulted by speeding cars, across an arching bridge, then upward again to the Botanic Gardens. And then I catch a glimpse of scarlet, and I’m greeted with the chatter and cartoon antics of kākā, who are returning to the city.

- A view through the Belgian Memorial Wreath. The wreath, which marks the centenary of the Battle of Passchendaele, is located in the Pukeahu National War Memorial Park.

- Six-metre-tall red sandstone columns display polished basalt panels engraved with indigenous art, part of the Australian ANZAC war memorial also located in the park.

In front of my apartment are the bright yellow orbs of Protoplasm, Phil Price’s 2001 kinetic sculpture. In a quintessential Wellington wind, they spin in odd, eccentric orbits. Art sculpted by the wind’s whim, ever-changing. It’s like a metaphor. I feel the shape of my own thoughts shifting. I’m bumped out of my orbit; invited to see life in different ways.

An evening walk takes me from Len Lye’s posthumous Water Whirler, that long slender rod, a joyful, twirling homage to wind and water perched on the end of a concrete pier along the water’s edge, where gulls emit discordant screeches and hover in wind gusts with trembling wings.

I pass a naked man standing on the edge of the walkway, arms outstretched, rusting torso tilting towards the water several metres below — Max Patté’s Solace in the Wind — and continue on, all the way to the angular architecture of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

- The Michael Tuffery waterfront sculpture Ngā Kina is surrounded by weekday lunch-goers. The kina shells symbolize the history and geography of the area — the Kumutoto Stream, which flowed from Woodward Street to the sea, and the location of the Kumutoto Pā.

- Artist Catherine Griffiths created 15 text sculptures that form part of the Wellington Writers Walk. Among the writers are Katherine Mansfield, Maurice Gee and James K. Baxter.

Walking Cuba Street one evening, I stroll past bustling cafés, past a man sleeping rough, past a busker who grins hopefully, when suddenly the sky shadows and rain sweeps down. I retreat into a doorway. Taped to the door is a sign: ‘Life drawing classes. Wellington School of Drawings.’

Two days later, I’m behind an easel, staring at a model, charcoal in hand, poised for my first life drawing class in 30 years. I have no idea where to start.

“Move your arm from the shoulder,” the tutor tells me. “The wrist makes small movements and gets stuck in detail.” “Right,” I say, rotating my shoulder. “Keep the charcoal light and loose. Draw quickly.”

The model holds a pose. Using a single line, I circle the head and draw the neck, protruding shoulder, breast, pelvis, hip thrust forward, hand on hip, thigh curve, knee bump, heel-arch-toe. I return, briefly, for a pouting lip. I’m so focused; my mind frees itself from clutter and, when I’m finished, two hours have passed. The drawing surprises me. The line feels unselfconscious and captures the spirit and movement of the pose.

In 2019, New York-based New Zealand artist Elliot O’Donnell (aka Askew One) painted this Bond Street tribute to Rita Angus.

I wake one morning and discover my walking has been taken from me. I have an inflamed lower back. Creeping down the stairs, gripping the bannister, is agonizing. I take two anti-inflammatories, rub in Deep Heat and Voltaren simultaneously, drink black coffee, curse getting older, tell myself I’m still young, zip up my coat and hobble down Lambton Quay to see Stella.

Stella works at the 30-year-old Natural Therapy Studio. I roll, plank-like, onto the massage table. Stella tells me she comes from an ancient line of practitioners of traditional herbal medicine. She began massage at 13 (my guess is about 40 years ago), working in the family clinic in China.

I’m hoping she might impart ancient wisdom on my back. She presses her tiny thumbs deep into my tissue and, for a while, I lie with hot stones warming my lower back. And then I know where I’m headed next: a 40-year-old sauna a 20-minute hobble away.

- Located in the Wellington Botanical Gardens, the 1994 Viewing and Listening Device by Andrew Drummond is a coil that one can crawl inside. From within, the funnel focuses the sound of the city. Finely balanced, a small push will set it moving.

- This war memorial in Pukeahu Park represents the trunks of an oak and a pōhutakawa, which intertwine to form a single leafy canopy, creating a whakaruruhau (shelter).

I push the door and step inside. A wall of heat envelops me. Left and right are benches made of cedar. The humidity triggers the timber’s natural fragrance, and a woody scent rides the air, mingled with eucalyptus. In the twilight emerge the reclining shapes of others. I limp over to a bench, roll onto my back and release a long sigh. The heat seeps in; my muscles uncoil, my mind unlocks.

I’m at the Tory Urban Spa, Wellington’s unisex sauna, first set up by an Austrian athletic coach in the early 1960s. Some regulars have been coming for more than 40 years. It’s a place for heat therapy, but also for rambling conversation with anyone present: an academic with a large skull tattoo on his back, a former estate lawyer who says he’ll never go back, a farmer whose teenage daughters are running rampant, a man whose wife has died. Twice. The last time a few months ago. The first 10 years ago. Alzheimer’s.

“When it happened,” he says, “it was like she passed away.” And with each conversation, there’s an aspect of their life that connects with mine. I can’t help thinking conversations with strangers bring out the best in me.

One of many wonderful examples of Wellington street art, this work, drawn in a ‘post-graffiti’ style, is created by a Kiwi artist named ‘Chimp’.

At the end of Lambton Quay, past the Katherine Mansfield sculpture with her alphabet laser-cut stainless-steel dress, up an alley, up a stairway, across the road, and there it is: La Cloche café.

“What’s that?” I ask, pointing to a cake, three layers of pastry sandwiched with custard. “It’s called a mille-feuille.” She speaks English, but for a minute I think it’s French. The earliest mention of a mille-feuille (a cake with a thousand layers) was in 1733 in an English-language cookbook.

It’s impossible to eat with decorum. I press down on the pastry. Custard oozes out the sides. The taste is delicious. I see myself as a mille-feuille aficionado, intending to mille-feuille my way across the globe. The cake collapses. A design fault, I think. Later, I discover a pâtissier has solved the problem by flipping the cake on its side and making the edge the top with a wiggle of icing.

A hint of winter is in the air one pre-dawn morning as I cross Civic Square. Something jeers at me. Perched on the Wellington Art Gallery’s rooftop is the giant hybrid face-hand sculpture by Ronnie van Hout. The anatomy is based on scans of the artist’s own body. Two “V” fingers point down. With the fog of sleep lingering, it feels like van Hout is giving me the fingers. I laugh and return the gesture with a “Winston Churchill” and stride towards the waterfront.

Mounted on the roof of the Wellington Art Gallery, the giant hybrid face-hand by Ronnie van Hout is based on scans of the artist’s own body parts. It’s called Quasi, after the character Quasimodo in Victor Hugo’s book, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.

At the end of the square is the City to Sea Bridge. Its weather-worn timber balustrades are decorated with contemporary Māori carvings by Paratene Matchitt. I pause and feel the wind on my skin. Face. Hands. I watch it whip the harbour into a white-tipped frenzy. Lights at the base of the Eastbourne hills flicker in the uncertain dawn. A ferry edges out of the harbour on its three-hour cruise to Picton.

The waterfront has a scattering of runners. The air smells salty. A large iron crane, mounted on a tug, creaks, bending to the wrench of wind and water. Sunlight, like a sword-strike, breaks through the dawn and ripples across the harbour. Light dances on hills and office windows and shakes its skirts over the harbour in a wild fandango that attracts the pale moths of yachts in droves.

Like the stretched necks of prehistoric animals, these streetscape toilets are given the name Kumutoto and are located at 59 Customhouse Quay.

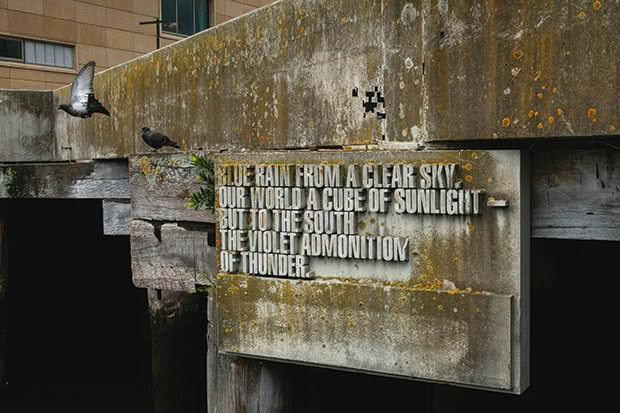

Below the walkway on a wooden pier is a poem by Joy Cowley made from small aluminium letters embedded in weathered timber. I look along the curve of the harbour.

I hear the lapping of water. It’s as if I’m standing inside the poem. Sunlight tickles the angular glass facets of the Deloitte building. On the other side of Te Papa, a myriad of yacht masts bob up and down in a wild fandango.

Poems run intermittently along the length of the waterfront, linking it end to end. Twenty-six letters arranged and rearranged, meaningful and metaphorical, planned for viewers’ accidental discovery. Pleasure to anonymous passers-by.

One of the many poems along the waterfront turned into sculpture by typographer Catherine Griffiths.

At the base of an unglamorous car park is Lamason Brew Bar. Inside, espresso machines hiss, levers clack, grinders whirr, patrons chatter, and the nutty aroma of brews and grinds wafts on unseen currents. Perched on a stool, I sip coffee brewed in a manner invented by Loeff of Berlin in the 1830s.

On the bar sit four bulbous glass chambers, a mini chemistry lab complete with Bunsen-like burners. Siphon coffee. Heated water creates a vacuum, rises up a chamber, then on cooling, flushes through coffee grounds on its descent.

- Hidden on Victoria Street is a 1987 sculpture by Terry Stringer. The statue, mounted on a high white plinth, is called Grand Head and is considered a quintessential Stringer work.

- The Spinning Top by Robert Jahnke in Woodward Street is a European version of the Māori pōtaka. The symbols are a pictorial history of Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

“I had my first siphon coffee,” I tell Jaya the barista, “in this dingy, elbow-wide coffee bar, in a corner of a Tokyo subway.” “When was that?” he asks, regulating the flame.

“Umm, 40 years ago… .” It was my first trip abroad. On the subway, I overshot my destination, disembarking at another station somewhere. The signs were not in English. No one spoke English. The skin on my face began to heat up.

I took refuge in a coffee bar, squeezed in between locals and placed my crumpled map on the bar. Someone looked at me. Other eyes turned. Someone slurped. I wasn’t sure where to look. The guy on my left placed a hand on my shoulder. It felt warm through my shirt. He pointed to the burners and said: “Gud,” and I felt a gush of gratitude.

Jaya, the barista at Lamason Brew Bar, prepares a siphon coffee, first invented in Berlin in the 1830s.

In his corner, the barista wielded a blade with which he carved club sandwiches as if he was doing mathematics. Cucumber club sandwiches. In Tokyo. Alongside, he conducted his symphony of siphons. I was lost in the subway and chance had led me to this small coffee bar to which I was unlikely ever to return. The ordinary, everyday people around me, unguarded in their morning coffee, the barista juggling his sandwiches and siphons — all became illuminated under my gaze, imbued with significance.

I caught the barista’s eye and gave him a thumbs up. He looked non-plussed, eyebrows drawn together. But then he grinned and nodded, his smile conveying contentedness. For a moment, I’m back in that low-lit bar; the intervening decades slipped from my timeline… . How fleeting it all is. Everything over in a blink.

I turned 60 in the year of Covid-19. Sitting sipping coffee at Lamason, lost in reverie, I think, “It’s the ordinary who are extraordinary. They’ll reach out and put a hand on your shoulder. And now and then, it pays to get off at the wrong subway station.”

The Lamason burners flicker beside me. I stand up and head off. In no particular direction.

MORE HERE

A mid-age bike-lover finds meaning in a Communist-era motorcycle

The edge of Mongolia: A photographer finds peace while riding with the Tsaatan reindeer tribe

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.