Video: Botanist Philip Simpson shares his love of totara

Botanist Philip Simpson shares why totara are one of the most amazing trees in the world from This NZ Life on Vimeo.

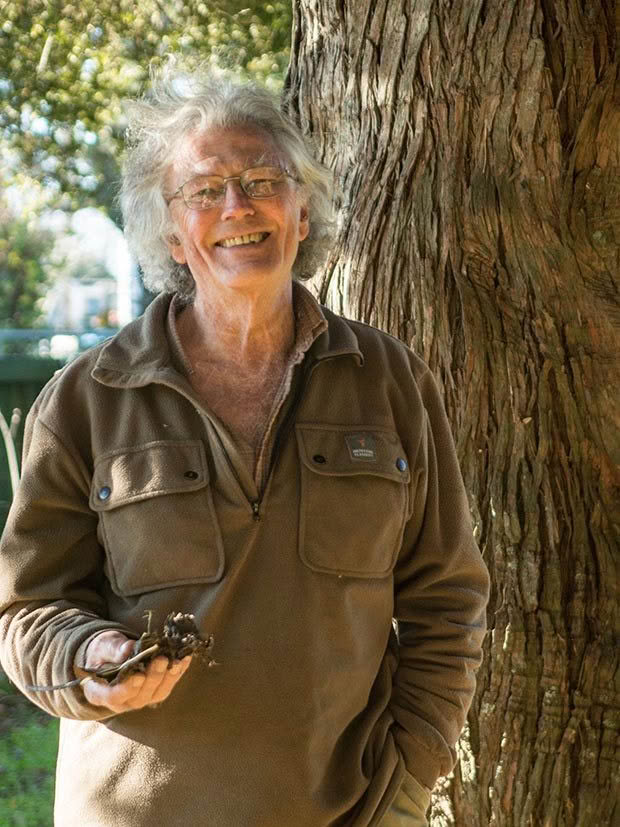

Our native trees are some of the most unique in the world, and so is the man who has dedicated his life to studying them and telling their stories, including his latest on the king of them all.

Words: Nadene Hall Photos: Daniel Allen Photography

Philip Simpson has dedicated eight years of his life to writing a book on what he considers to be the most magnificent of New Zealand’s native trees, but the botanist and author has just one on his Takaka block which is mostly covered in regenerating bush. It’s barely 30cm high, and that it is so young and on its own, and that so much tōtara in NZ is now at this stage is one of the reasons he felt compelled to tell its story.

Giant tōtara, more than 1000 years old, used to cover a lot of NZ’s landscape, but not today. Renowned conservator Stephen King and others had to set up a protest in the canopy of tōtara in the Pureora Forest back in the late 1970s to successfully save the ancient forest home of the most famous of tōtara, Pouakani (see box at 12).

Philip is one of the few people to have seen Pouakani and most of the other aged tōtara trees still left. There aren’t many.

The tallest and probably oldest tōtara in NZ is Pouakani, the stunning cover star of Philip’s book. It grows in a forest near Mangakino, 60km north-west of Taupo. It is estimated to be 1750-1850 years old, stands 42m high, and has a girth of 11.92m. To give you an idea, a standard bus is 10-13m long.

“For me to go and see a mature tōtara tree that is say 500 years old, I personally only have to travel 20 minutes because I know where one is – but only one. For some people in some areas they would have to travel hundreds of miles to find such a thing.”

That’s because tōtara was the star of European settlement in NZ. All the things that made it the most valuable of trees to Māori – it’s a light, rot and water-resistant, straight-grained, easy-to-split, easy-to-carve wood – were also of enormous value to settlers, who cut down forests at a time to build houses, bridges, railway sleepers, wharves, furniture and art.

A tiny totara seedling. Seedlings can stay this size for a year or two, fighting to survive the elements.

You can still see the remains of these trees if you are travelling through rural parts of NZ. Keep an eye out for old telegraph poles in paddocks with a tell-tale wider base and narrower top, or old, slightly unevenly cut, mossy fence battens and posts. You’re probably looking at the remains of our oldest tōtara.

“Tōtara was highly valued,” says Philip. “Wherever it grew it was harvested. We’re just left with a few scraps now, one or two are marvellous such as Pureora (north of Taupo), Whirinaki (near Rotorua) and Pohangina (north of Palmerston North).

Philip and Wendy’s block is 100m above sea level and has a panoramic view of Golden Bay.

He and wife Wendy Parr, a wine scientist, live on a rugged limestone hillside along a dead-end gravel road, minutes from where he was born and from the large valleys of tōtara and other natives he began exploring from a young age. There aren’t many children who would head out into the bush to take samples and make notes about native trees. But in the foreword to Tōtara, childhood friend John Mitchell describes how Philip – aged just five – was already on the job. It seems a passion for plants runs in the family, as Philip explains.

“My mother’s grandfather was a fern collector. Ferns in Victorian New Zealand were pretty marvellous, pretty famous, and I’ve got his fern collections in my office now, they’re dried specimens, they’re now 150 years old.

“My parents had a nursery as well as a farm, so I grew up propagating plants, taking cuttings, helping with the grafting and so on. I started right from the day I can ever remember, collecting herbarium specimens, drying them in newspaper, placing them on a sheet with notes about them. I started learning the name of native plants and collecting them and so on and that’s basically been my entire life.”

Telling the personal stories of trees and bringing them to life to people today is Philip’s gift, and it’s extraordinary. He already has two award-winning books as his legacy. Dancing Leaves is about the cabbage tree. When large numbers of cabbage trees started dying off in the 1980s, Philip got the job as DoC’s expert and one was of the leaders of the conservation efforts.

His other is Pōhutukawa & Rātā: New Zealand’s Iron-hearted Trees. So it won’t surprise you to know that both Philip was a founding member of Project Crimson, a group born from research which showed back in the late 1980s that more than 90% of coastal pohutukawa stands in NZ had been eliminated. Today, Project Crimson has organised the replanting of more than 330,000 trees.

When he was granted $100,000 by the Michael King Writers’ Fellowship and received other funding by various groups back in 2009, Philip was originally thinking of writing about the Joshua tree (he did his PhD on it back in the 1970s). But he decided to complete his trilogy on NZ natives and chose what he describes as the most chiefly of all the trees.

“It’s not written only for scientists by any means, I want people to understand what tōtara is, what it’s meant to people throughout the ages.

“We don’t live in the forest but we are basically a forest species as humans. Trees are very important to people. They live for such a long time and their beautiful form, highly useful in terms of their products like timber and food and so on.

“Trees are basically my business. I’ve always been involved with growing trees and appreciating them. It’s not difficult for me to see human history through trees, especially in New Zealand where we are surrounded by the most magnificent and interesting trees, like tōtara but the others I’ve worked in, like cabbage trees, they’re quirky and idiosyncratic, but they are very much part of the New Zealand landscape and the way New Zealanders see themselves.”

One of the more rare natives growing around Golden Bay is a species of mahoe (whiteywood, Melicytus obovatus), only found on limestone in this area.

The tōtara may be missing from his block, but Philip can appreciate the natural wonders that are popping up amongst the very rocky, wild land he lives on. It is the site of a former cement works and used to be quite a miserable place, covered in a thick layer of spewed limestone dust. It closed in the 1980s and when the rain washed the dust away, it left behind a gem.

“We’re in the rare position of having a piece of land that’s actually got some nice flat paddocks, so it’s perched up looking down onto Golden Bay itself, 100m above the sea, and there’s beautiful paddocks for our handful of sheep and our little vineyard.”

The rest of it is regenerating bush, and Philip can point out some of the more unusual local beauties that anyone else would probably overlook.

“We’ve got a lot of tree ferns and kanuka and whiteywood and so on. But this is north-west Nelson which botanically is a very special part of New Zealand. It’s got greater diversity in terms of species than most parts of New Zealand, and we’re on limestone and that means you often get species of plant that are restricted to limestone. Our bush has got quite a few species that are local endemics… that sort of thing is rather interesting.”

There’s a species of mahoe (whiteywood) called Melicytus obovatus, and one of five finger which are found only on limestone in this area. But the flashiest is a species of kowhai.

“It’s a kowhai called Sophora longicarinata and it’s characterised by having very long, tiny leaves, so that’s found only here. It flowers up behind the house on the limestone, the tui spend a lot of time feeding on the nectar.”

There are also fruit, olive and nut trees and a large vege garden growing around the house, and it’s important food for him says the 71-year-old.

“I do have to try to look after my health. Having a good diet is important. I have a nice vege garden. It’s a bit of wreck at the moment but it’s productive. Just yesterday I harvested some jerusalem artichokes, that was a great thrill – I haven’t grown them in a long time so we’re looking forward to them.”

Philip works from his office at home, occasionally travelling to get information he needs. He got to visit many forests of old tōtara, and he’s hopeful New Zealanders will realise what an asset new plantations of tōtara could be.

Tōtara may be the subject of this book, but Philip says these days he’s in awe of all natives. He has been out in the bush cataloguing native species since he was five years old.

“It’s very potent, quite capable, but it does need to have the space to do so. The soils that it likes are the soils that we like and so there’s a bit of a clash there.

“We use pine trees for buildings and it’s marvellous. However it’s not a very good timber in terms of strength or durability or appearance. I would love to think in the distant future, generations of New Zealanders will be able to harvest purposefully-grown woods of tōtara and experience the beauty and value of one of the world’s most wonderful and beautiful timbers.

“That’s my view: protect the old trees that we’ve got, and manage the weedy ones and plant woodlots for future timber supply.”

Philip’s next project will be on Abel Tasman National Park which is a handy five minute trip down the road.

“It’s a huge topic. Every topic is enormous. Right now for instance I’m looking at mosses of Abel Tasman National Park and it would take a lifetime to actually come to grips with it and I have to come to grips with a subject in a few days. It means it’s very exciting because I’m discovering new stuff all the time as far as I‘m concerned but it puts pressure on me to be able to communicate about a topic when I don’t know a huge amount about it. But I need to try to stimulate others to get something out of what I say about it.”

He may not be running around the bush like he did when he was five, but his passion for trees is as strong as ever.

“Being over 70 and towards the end of things is a problem on the one hand in terms of one’s physical ability to rough it. But on the other hand, it gives you the wisdom. The amazing thing about life is it’s a journey, you can’t go back and do it again, so everything you do is a one-off and it all contributes to one’s story.

“I’m really pleased to have been able to have a healthy, creative life and being able to benefit from the joys of this society. I feel privileged.”

“Even going back to tōtara, it’s not in danger of extinction by any means, but it’s still very vulnerable to predation and disease as various fungus diseases that have been introduced into the country.

“It’s a special part of New Zealand.”

Golden Totara foliage.

5 GREAT REASONS TO PLANT TOTARA

If you live north of Auckland, you might even consider tōtara a bit of a weed, popping up along fence lines and in pasture, a bit like gorse.

• There are four species of tōtara including lowland tōtara – the most common you’ll spot on farms – Hall’s tōtara, snow tōtara, needle-leaved tōtara, and a hybrid, South Westland tōtara.

• Totara are easy to grow. “You can be sure they’re going to succeed,” says Philip. “Some natives are quite difficult to grow, but tōtara don’t mind being out in the open, they can handle the sunshine, the gangly youth seems to be pretty powerful in our current weather patterns, and they don’t seem to mind a lot of rainfall either, they can handle a wide range of conditions.

• Totara trees make great hedges if planted around 1m apart and trimmed yearly, turning into a dense wall of foliage that’s quite prickly, making it a good security deterrent, and great habitat for birds.

• Totara are fairly immune to pests and disease.

• You can get cultivars of tōtara in different colours, including gold (Aurea) and blue (Matapouri Blue).

Totara berry.

WHAT YOU MIGHT NOT KNOW ABOUT TOTARA AND POSSUMS

Thousands of tōtara trees die every year, and it’s often due to murder by possums. You wouldn’t think there would be much for possums to munch on, but at certain times of year the tōtara is vulnerable.

“They bother with the young leaves in spring, and also the buds before they open out,” says Philip. “And I’m not quite sure about the difference in chemistry between lowland and Halls tōtara but all tōtara gets severely damaged by possums and all through NZ it has been killed in its hundreds of thousands. In some places like the Ruahine Range in southern central North Island, Halls tōtara has been virtually eliminated.”

But have you ever seen a possum in a tōtara?

“I searched long and hard for a photograph of a possum in a tōtara, all the top nature photographers in New Zealand like Rod Morris and so on. But of course they are nocturnal and going out and looking for possums is not everyone’s cup of tea.”

However, it is Philip’s cup of tea.

“I spend quite a lot of time outside at night with possums because they’re here and I shoot them. I don’t like doing it, they’re beautiful creatures in their own way, however they do so much damage and New Zealand is being ruined by pests, especially the ones that eat birds: possums, stoats and rats.”

A MIGHTY TOTARA FALLS

You’ll sometimes hear people referring to a ‘mighty tōtara falling’ when someone important dies. It comes from an old proverb, denoting how valued the tōtara tree was to Maori culture:

“Kua hinga te tōtara i te wao nui a Tane.”

“The tōtara has fallen in the forest of Tane.”

WHY CLIMATE CHANGE HAS STOPPED THE WINE

There are around 1000 vines on 1ha (2.5 acres) of the limestone soil on Philip and Wendy’s block. Wendy is a principal research officer for the Department of Wine, Food & Molecular Biosciences at Lincoln University and has a PhD in wine science which means the couple has produced impressive chardonnay and pinot noir in low volume from their small site.

But they are choosing to wind it down as the effects of climate change take hold.

“We’re already one of the wettest vineyards in the world because we get West Coast rain here,” says Philip. “We get Nelson sun and West Coast rain and it’s quite a nice combination, but the rainfall is creeping up.”

Annual rainfall has now hit 2000mm, although it’s not the rain itself which is entirely to blame says Philip.

“What seems to be happening, the oceans are warming up and evaporating and there’s more water vapour in the atmosphere. While that can translate to increased rainfall, it definitely translates to increased cloud – we’re faced in the last year or two with a deteriorating weather pattern.”

The grapes still grow but Philip says that wine quality is at risk if they carry on.

“We’ve had a period of great fun and learning and experience, but in the last five years things have really dramatically changed.”

THE SHEEP THAT’S NOT A BREED

At some point in the future, when he has time, Philip wants to get into weaving. He chose a brown sheep breed – “just to be a little bit different I think!” – and went for some of the rarest in NZ.

“It’s not a breed really, it’s a lack of a breed which is the interesting thing. Originally they were merinos but they come from South Canterbury where they escaped from a farm and went up into the mountains and went feral for several generations. They lived together in a little clan and they reverted to a form of sheep probably very similar to ancestral merino.”

The result is brown sheep with white on the top of their heads and the tips of their tails, that grow a very fine wool.

“I would love when I grow up to weave rugs. I haven’t done any weaving yet but I’ve kept all their wool. I’ve got a shed full of brown wool.”

8 THINGS YOU MAY NOT KNOW ABOUT TOTARA

• ‘To’ means stem or stalk; ‘tara’ means spiky or sharp.

• Tōtara was the first New Zealand plant to have its Māori name formally adopted as the species name.

• Tōtara are conifers. In the rest of the world these are mostly short trees, but in NZ we have the most enormous and unique conifers found on Earth, including tōtara, rimu, kahikatea, matai and miro.

• Tōtara was the important tree to Māori in their everyday life, with the wood used in carvings, and the bark shaped into storage containers (patua and pōhā) for preserving food.

• Nearly all of the most treasured carvings in New Zealand are made from tōtara.

• Māori earmarked trees 200-300 years ahead of time as potential waka. Bark would be removed along one side to stop the core of the tree growing. Edges would continue to grow, leaving a hollowed-out tree centuries later that could then be worked into a waka.

• It can take a couple of years for a seed to get to a few centimetres in height in a forest situation; the average adult tōtara is 20-25m high.

• Old tōtara posts and stumps are having their heartwood harvested for a compound called totarol which has antibacterial and antimicrobial properties and is the reason why the wood is resistant to rotting.

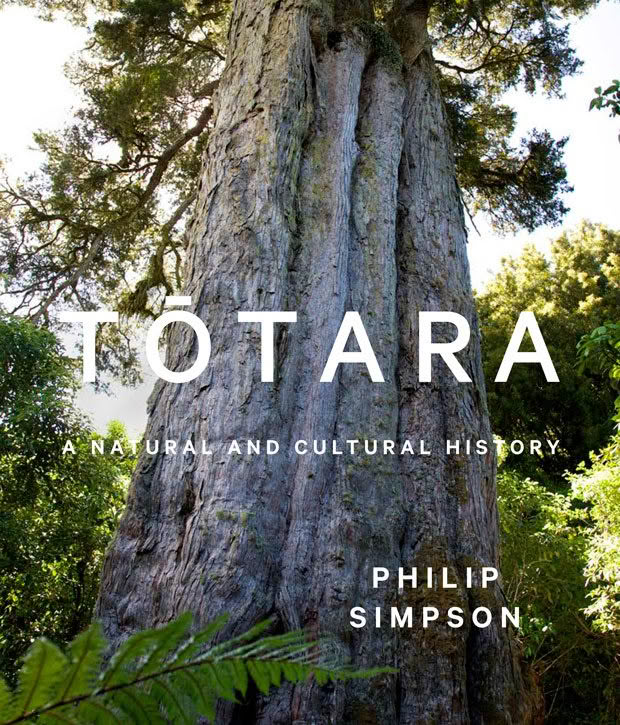

Tōtara – A Natural and Cultural History

By Philip Simpson

Auckland University Press, hardback, 300 pages

$75, buy online here

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.