Veterinarian and romance writer Danielle Hawkins reveals her not-so-glamourous guide to raising lambs

She’s famous as one of NZ’s most popular romance writers, but Danielle Hawkins’ other job is always calling her. Sometimes, from the washing basket in the living room.

Words & images: Danielle Hawkins Additional images: Tessa Chrisp

I love lambs. All baby animals are cute, but lambs are ridiculously cute. No other animal has such cool eyebrows. I love the way they race around in little gangs or line up and take turns to jump off a bank. The kids adore them, and saving lives gives you a lovely warm, virtuous glow.

That’s how I feel in the first week after lambing starts.

Then there’s week four, when I’m heading out in the pouring rain at 8pm with 15 bottles, which will need to be refilled two more times for two more groups of lambs.

There are three brand new triplets in the firewood box in the sitting room, all of them peeing like horses and bleating at the top of their lungs. Then I’m tube-feeding a limp, sad little lamb with pneumonia in the washing basket.

Each feed takes an hour and a half, and each lamb is on four feeds a day. By now, the kids are completely over it.

I have to admit that even my warm glow is beginning to cool a little.

Last year was particularly bad. We have 1200 ewes, and we always end up rearing 20-odd lambs, but in 2018 the numbers peaked. I’ve done my best to repress the memory, and it’s all a bit of a blur, but I think it was 45.

Two hundred of our ewes had triplets, and sheep just aren’t designed to have three lambs. Late pregnancy is a dangerous time for a 65kg ewe carrying 25kg of lambs, placenta, and amniotic fluid.

Just imagine walking around the hills with all that weight strapped to your front. They’re prone to getting cast or pushing out a bearing or, in a few, awful cases, having their abdominal muscles rupture from the excess weight. Every day, it seemed, my husband Jarrod came home for lunch carrying yet another set of newborn triplets.

HOW TO REAR ORPHAN LAMBS

This is not the only way to do it. It’s just how we do it.

As soon as a new lamb arrives, it gets 150ml of colostrum. Lambs are born with no immunity. They don’t inherit antibodies to various diseases from their mothers before they’re born. The protective antibodies are all in the colostrum, and lambs are vulnerable to infection until they have that first drink.

We use the powdered cow colostrum you buy from rural supply stores. Ewe colostrum is the best, but fresh cow colostrum is fine too if you can hit up a friendly dairy farmer.

Unless the lamb is brand new and I know it hasn’t been wandering lost around the paddock before it was picked up, I also give it half a millilitre of penicillin. I don’t like using antibiotics unnecessarily, but I really don’t like seeing a lamb thrive for three days and then succumb to an infection it picked up before it had colostrum.

If the weather’s nice – or if the lamb is particularly noisy and I suspect it’s the wake-twice-in-the-night-and-yell-for-food type – they go straight outside into the baby pen.

Sick or cold lambs spend a day or two in the firewood box in the living room, sitting on a hot water bottle. They get five colostrum feeds for the first day or so, and then go onto milk powder.

A wheatie bag keeps a sick lamb warm.

I’ve spent years wrestling with buckets of home-made yoghurt, which prevents bloat. But it also clutters up the hot water cupboard. It has an annoying habit of getting the wrong bug in it and going thin, sour, and watery.

Now I have discovered the joys of Sprayfo whey-based milk powder. It’s supposed to prevent bloat, and it seems to work. A few of last year’s lambs succumbed to a sprinkling of other random illnesses (sometimes I think they do it on purpose), but none got bloat.

The back of the milk powder bag assured me that the lambs could handle two feeds a day at a ridiculously young age. I didn’t believe it and stuck with four feeds for weeks. But my sister did what it said. Her lambs looked, annoyingly, as good as mine.

- Lambs taking over.

- Blair and Katherine Hawkins helping out.

You can bottle-rear lambs and feed them four times a day for weeks on end. You can supplement them with meal, which they happily eat if you offer it from day one. They spend the first week playing with it. If you try to introduce it later on, they reject it with loathing.

But the depressing thing is that they never look as good or grow as well as they would on their mothers. If I only had a couple, or if money was no object, I’d feed them milk ad lib. Friends of ours do this, and their orphan lambs put mine to shame. They go through twice as much milk powder, which gets frighteningly expensive when you’re feeding a lot of them, but the lambs look amazing.

Our lambs get fed a whey-based milk powder which we’ve found helps to prevent bloat.

Although I’ve read various things about how to rear orphan lambs profitably, I strongly suspect that the only way to do it is to sell the little darlings on Trade Me.

Rearing orphan lambs might not be the most cost-effective use of time, but neither Jarrod nor I have ever managed to drive past one. And I love it. At least, I do from December to August, when I’m not feeding lambs, and my memories of the whole experience have taken on a rose-tinted, nostalgic sheen.

WHAT TO DO IF A LAMB WON’T SUCK

I tube feed lambs that won’t suck with the super-awesome Trusti Tuber from NZ company Antahi.

It’s specially designed so milk can’t go down the wrong way, even if you’re a beginner to tube feeding.

Trusti Tubers for lambs/kids and calves are available at vet clinics nationwide.

4 THINGS LAMBS DIE OF

Lambs may die, apparently sometimes just to spite you – this isn’t an exhaustive list! – but here are four common reasons.

1. Abomasal (ie, stomach) bloat

Lambs are designed to drink little and often, but most people can’t commit to feeding them 17 times a day as their mothers would. We feed them more milk, less often.

If they happen to have the wrong type of bacteria in the stomach designed to digest milk (the abomasum), the milk breaks down and produces a large amount of gas, which blows up the stomach like a balloon. Abomasal bloat usually kills the biggest, best lambs, often the night before Ag Day.

A sad-looking, non-drinking lamb with a tight, round stomach is an EMERGENCY. Call the vet straight away. Don’t wait and see how it goes.

It’s much better to prevent bloat than to treat it – yoghurt milk, whey milk powder, and ad lib feeding from birth are all good strategies.

2. Arthritis (joint infections)

This usually appears on day four, when your lamb starts limping. It’s almost always caused by an infection the lamb picked up before it got colostrum when it was wandering sadly looking for its mother and sucking all sorts of grubby things in the hope of finding milk.

They need antibiotics and pain relief straight away, the sooner the better, and they should be treated for at least a week. If you only give them antibiotics for three days, they improve and then start limping again next week – I know this from bitter experience.

3. Thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency

Thiamine deficiency affects the brain. You see a dopey lamb, progressing to a blind one, progressing to a lamb having a seizure with its head thrown back. Treatment is pretty successful if you do it quickly enough. A thiamine injection from the vet works best, but as an emergency stop-gap, you can try feeding them marmite.

4. Watery mouth

This is a horrible disease affecting lambs up to three days old. It’s due to a stomach infection (E. coli), picked up before the lamb gets colostrum. Lambs can’t stand, they dribble profusely, and if you put your finger in their mouth, it’s stone cold.

I’ve tried treating them with very little success – I think it’s probably kindest to put a lamb with watery mouth out of its misery.

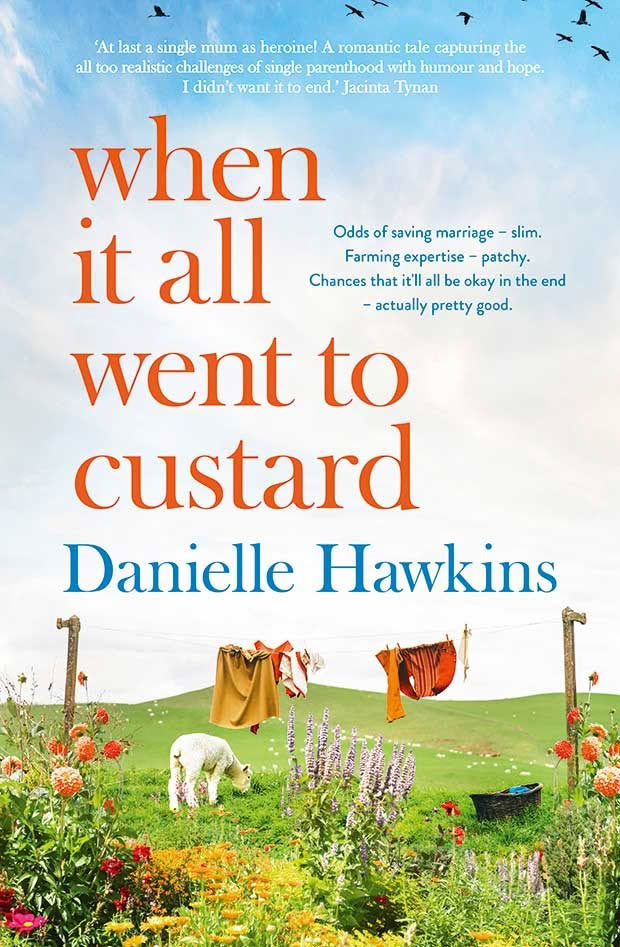

When It All Went to Custard

By Danielle Hawkins

Harper Collins, paperback, $35

Odds of saving marriage – slim. Farming expertise – patchy. Chances that it’ll all be okay in the end – actually pretty good. Bestselling author Danielle Hawkins’ latest novel is the story of the year after Jenny’s old life falls apart.

Of family and farming, pet lambs and geriatric dogs, choko-bearing tenants, and Springsteen-esque neighbours. And of getting a second chance at happiness.

MORE HERE:

Waikato vet Danielle Hawkins draws on country life for popular romance novels

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.