What unusual eggs can tell you about your hens

Sometimes the nest box holds a little egg of horrors.

Words: Sue Clarke

One of the main reasons for keeping a few hens in your back garden is for the eggs they will produce. Humans have been fiddling with the genetics of poultry for thousands of years. We’ve created types that breed true in the last couple of hundred years, and laboratories to refine egg and meat production in the last 70 years or so.

The variety of breeds of Gallus gallus has expanded to encompass the various needs of breeders and fanciers throughout the world, whether you like beautiful feather patterns, lots of eggs, or something that makes a good roast. One of the big factors in all of that genetic meddling is the kind of egg you buy in the supermarket. These don’t vary in size much. For the most part they are uniform in shape and shell, carefully graded and selected, inspected inside and out, and you’ll only ever see perfection.

But when you keep your own flock, you know there are all kinds of anomalies that can be produced by your hens. Some are weird and wonderful productions, and some are pretty disgusting. It pays to know what caused them, and to know if it’s fixable and whether you can you still eat it or not. Eggs can be odd in a number of ways: shell deformities, wrinkles, deposits, ‘extensions’. Sometimes the egg will have no shell at all or a very thin one. The shell may vary in colour from white to many shades of beige, brown through to rich mahogany, and then there are the shades of blue, green and olive.

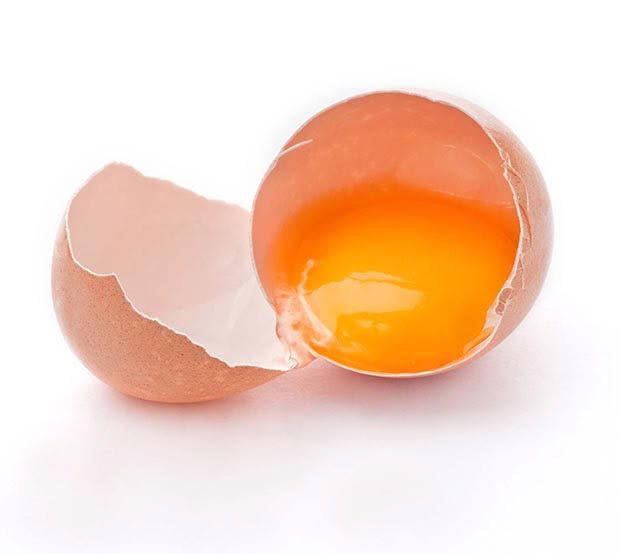

Shell colour is dependent on genes and breed, but when a hen lays an egg in a colour that is faded compared to her normal offerings, it can be due to a problem. Internally there can be inclusions like blood spots, meat spots, sometimes even another fully-shelled egg. If you have roosters, hopefully you won’t find a partially-developed embryo when you crack it open, or just as bad, a wriggling worm.

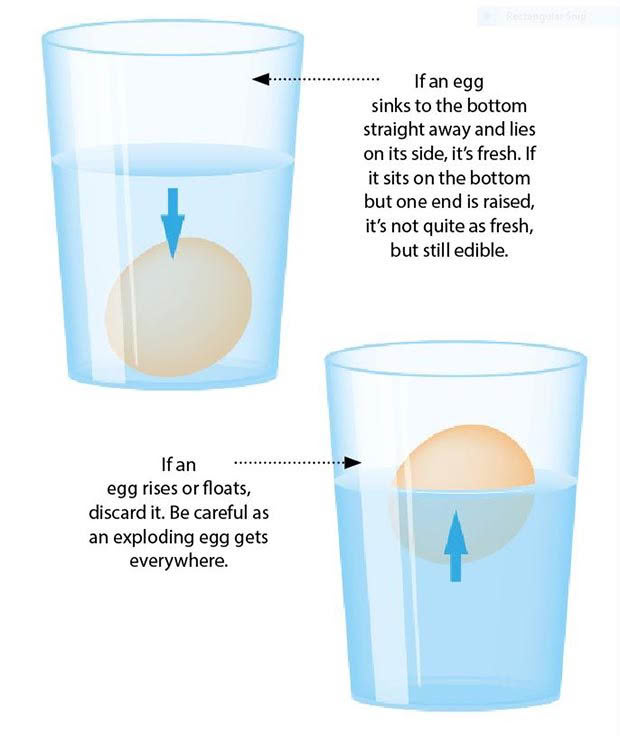

WHAT TO DO WITH EGGS FROM A SECRET NEST

If you do come across eggs in a secret nest and you’re not sure how long they have been there, you can do the float test. Place the eggs in a bowl or bucket of water. If it sinks straight away it is fresh. If it stays on the bottom but one end raises up, it is not quite as fresh. If it stands on its end it is getting old and stale. If it floats, treat it gently and dispose of it as it’s a sign it’s full of gas and you don’t want that to explode anywhere near you. Consider also the condition of an egg in a secret nest, even if it passes the float test.

If it’s covered in dirt or manure, it’s best not to risk eating it. The shell of an egg is porous and will absorb bacteria through it, which could cause you problems. If you still want to crack an egg open and you’re not confident about its age, crack it into a separate bowl just in case it’s hiding a nasty surprise.

WHAT IS A CLUTCH?

A clutch is a group of eggs laid by the same hen on consecutive days. When the hen completes her ‘clutch’ her instinct can be to go broody and incubate them. In many heavy heritage breeds this may be 12-15 eggs laid on consecutive days. Modern commercial hybrids are selected for their abilities to lay large clutches of eggs without taking a day off, perhaps 30 or more.

Each egg is laid slightly later each day on approximately a 25 hour cycle. Once the last egg is laid in the late afternoon, she may take a one day break and then lay again the following dawn, 36 hours later. Hens which have 20-24 hour cycles often lay bigger clutches without taking a break.

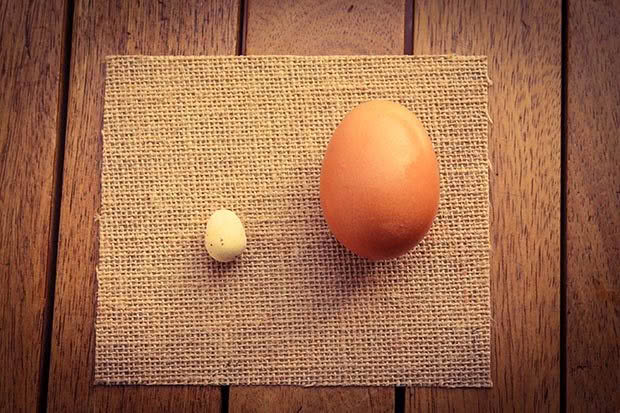

1. TINY EGGS

A very small egg – often called a wind or fart egg – will be the right shape but very small, and often will have little or no yolk. Sometimes this may be the first or the last egg in a clutch. Tiny eggs are most commonly laid by pullets, often due to their bodies getting used to the flush of reproductive hormones and stress.

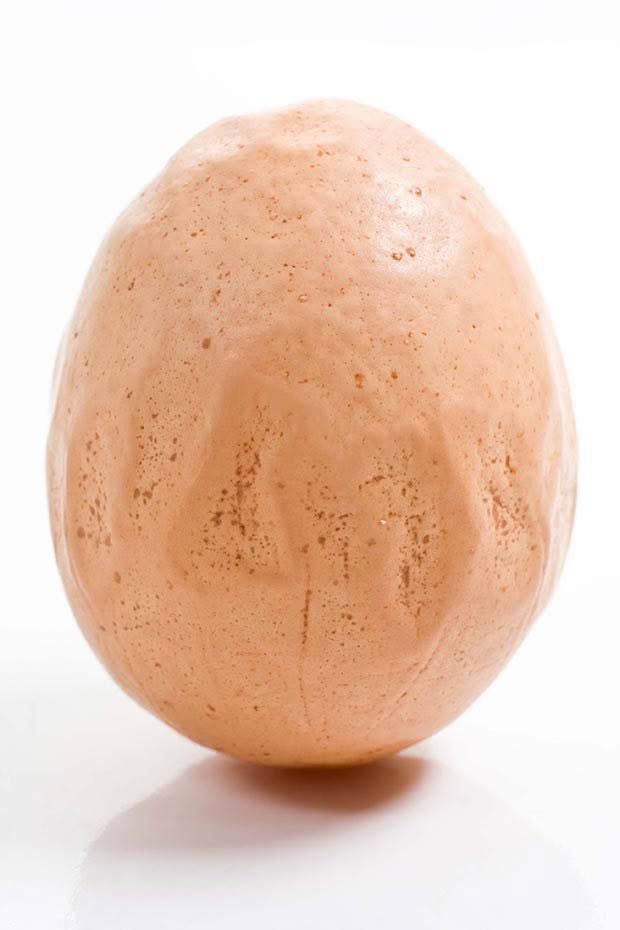

2. ‘LASH EGGS’

The appearance of irregular blobs of material in the nest or partial membranes surrounding these blobs are ‘lash’ eggs. They might be sort-of egg-shaped but they aren’t eggs. These are solidified pus from an infection in a hen’s oviduct, and may or may not contain some secretions which are partial membranes. It might look egg-shaped, but a lash egg is actually solidified pus. Never eat this!

3. WRONG SHAPED EGGS

Everyone expects their eggs to be smooth and egg-shaped, but that shape depends on the breed of hen, and the individual bird.

The same hen will tend to lay the same shape of egg every time. Some hens lay eggs that are more pointed than others, some more rounded. It does tend to be a breed feature, or may be due to the genetics of an individual hen.

There is a myth that shape can tell you whether an egg is fertile or what sex the chick will be. Neither is correct. All pullets (females in their first year of lay) will start their lives laying fairly small eggs. You might see the odd egg missing its shell or the shell may be unusually thick. After a few weeks a pullet’s eggs will become bigger, more uniform in shape, and the shell will become stretched over more content and settle into a standard thickness.

Commercial hybrid hens are selected for their abilities to lay a good-shaped egg which has excellent shell strength and resilience. The trait is heritable, so if you select your own hens to breed from and choose ones that lay eggs which are well-shaped and strong, her daughters will tend to do the same.

4. FUNNY SHELLS

Various outside factors can affect shell quality. Diet, disease, stress, and even the amount of Vitamin D in the diet – plus that made by the bird when exposed to sunlight – have an effect. There can also be problems with the shell gland (which secretes the hard outer covering) causing various discrepancies to occur.

Calcium pimples.

Wrinkles, flat-sides, sandpaper-like roughness, calcified pimples, body checks and seemingly mended cracks are all fairly common. Thin shells which crumple easily or no shell at all, are also common. If a hen is roughly handled, stressed, caught or chased when the egg is being formed, you may see wrinkles, crumples and cracks which have solidified. But if you see these types of fault regularly from the same hen, it can be either genetic or she may have a defective shell gland. If you constantly find funny-looking eggs, it may be a genetic issue for a hen.

Calcium pimples are more common on the eggs of older hens as their reproductive system isn’t as efficient. It can also be a sign of excess calcium in the diet. Extra calcium should be offered in a separate dish any other feed – don’t force it on the hen by mixing it into her main feed.

TIP OF THE MONTH

Poultry have very specific protein, vitamin and mineral requirements, and the base of their diet should be a well-balanced, good quality poultry feed that is correct for their age and needs. From 0-6 weeks, chicks require Starter feed (high in protein, low in calcium); from 6-18 weeks Grower (slightly lower in protein, still low in calcium); from 18 weeks onwards Layer (slightly lower again in protein, much higher in calcium).

If you don’t have Grower feed available, keep chicks on Starter until 18 weeks of age, rather than switching them over to Layer feed – the calcium level is too high and will affect their kidneys, often causing death when the birds are stressed.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.